In last week’s column I indicated the commencement of a new series aimed at addressing burning considerations surrounding Guyana in a time of oil/gas production and export. As a lead-in to this, I start with a brief survey of Guyana’s extractive sector, focusing on mining, quarrying, and forestry. Last week’s notion of the qualitative impact that oil/gas production and export would have on Guyana’s production possibilities was emphasized. And, to describe this notion carefully, I introduced the concept of potential output, which is an analytical device that will be employed in the discussion to come.

On reflection, however, there are two other similarly basic, simple, but necessary notions, which should be introduced at the outset. Both are used extensively by NGOs and CSOs, reporting on Guyana’s sustainable development. One is the notion of Guyana’s output gap. This is the difference (expressed as a percentage of its potential GDP) between actual reported GDP and what it could be potentially, as defined in last week’s column, “what Guyana can produce when all its resources are properly applied and fully utilized”. While this sounds like an attractive definition, I must warn readers, there is little agreement among analysts that sustainable potential output for any economy can be satisfactorily established.

On reflection, however, there are two other similarly basic, simple, but necessary notions, which should be introduced at the outset. Both are used extensively by NGOs and CSOs, reporting on Guyana’s sustainable development. One is the notion of Guyana’s output gap. This is the difference (expressed as a percentage of its potential GDP) between actual reported GDP and what it could be potentially, as defined in last week’s column, “what Guyana can produce when all its resources are properly applied and fully utilized”. While this sounds like an attractive definition, I must warn readers, there is little agreement among analysts that sustainable potential output for any economy can be satisfactorily established.

The other notion is used by NGOs and CSOs as a substitute and/or supplement for GDP: total wealth. This notion, however, is equally imprecise and incapable of satisfactory measurement. Total wealth supposedly includes 1) Guyana’s natural resources; 2) its assets as applied when measuring the GDP; and 3) its peoples, with their skills, organisation and community structures.

Extractive sector

Guyana is considered by most analysts as well-endowed with mineral resources. The primary ones are bauxite, gold, and diamonds. The bauxite industry is effectively owned and controlled by overseas investors. The gold and diamond industry is much more diverse in its ownership structure, with the larger operations being generally foreign owned and controlled. In recent years sand production has been reported on separately in the Annual Reports of the Bank of Guyana, where it presently stands at about 850 thousand tonnes (2014), up by about 200 thousand tonnes on 2012 production levels.

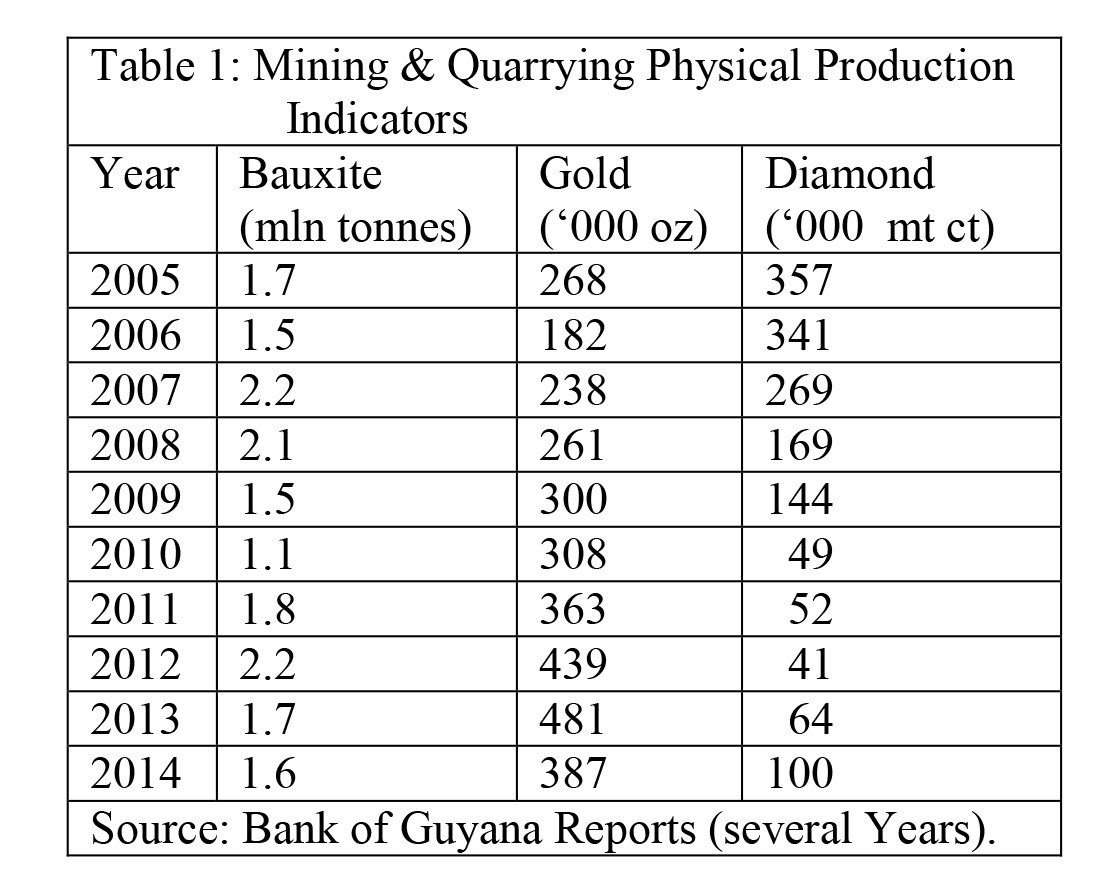

Table 1 shows output of the main mining products for the decade (2005-2014). Certain features stand out from this Table.

First, all three products exhibit significant variations in output. Thus bauxite output has ranged from a peak of 2.2 million tonnes in 2007 and 2012 to a trough of 1.1 million tonnes, in 2010. Similarly, gold output has fluctuated from a low of 182,000 ounces in 2006 to peaks of 481,000 ounces in 2013 and 439,000 ounces in 2012. The production of diamonds has witnessed a drastic collapse from 357 mt cts in 2005 to only 41 mt cts in 2012.

Second, despite these variations, certain trends are discernible: 1) the decline over the years in diamond production; 2) fairly stable ranges of bauxite output during recent years 2011 to 2014; 3) increased output of gold, following the emergence of the Great Depression in 2008, and the rise of gold prices as the flight to security took hold of global investors.

Third, since none of these mineral products are replenishable, only new discoveries at cost-effective prices can assure Guyana’s supply expands. Already, there are allegations of irregularity as “blood diamonds” are supposedly being substituted for Guyana’s declining supply of diamonds to the world market.

Fourth, the price of these products remains, perhaps by far, the greatest influence on how much is produced. And, since the production of these products mainly takes place in the hinterland/interior regions, this poses major environmental challenges.

Pitfalls of resource extraction

Worldwide, western economists portray mineral resource extraction in small, poor, undiversified and trade-dependent countries as a catalyst for their GDP growth, economic progress, national and individual welfare (well-being). This resource extraction has, regrettably, also taken an immense toll on the exposed, vulnerable, and dispossessed sections of society, both through its macroeconomic and microeconomic effects.

Mistakenly, Caribbean-based NGOs and CSOs posit the neoliberal (World Bank) view that resource extraction adds to total wealth (itself a World Bank construct). And, as such, this ensures its net macroeconomic effects will be positive. And, as a consequence, the main policy focus should be on managing the microeconomic distortions resource extraction creates.

Why do they hold this view? I believe it is because resource extraction can 1) increase actual and potential output; 2) generate foreign exchange; 3) yield added government revenue; 4) enhance investment flows. In an economy like Guyana’s, it is assumed that all these occur! The proof of the pudding, however, lies in its eating. This means that it depends on how these macroeconomic gains are inserted into the country. The issue is, therefore, which groups gain, and which lose. And further, can the winners ‘bribe’/’compensate’ the losers to let them make their gains, and still be better off? If this is not established, positive macroeconomic gain, which must mean that, in effect, all are being made better off, cannot be assured, if gains go to some, and losses to others.

Next week I shall continue with this discussion.