By Vidyaratha Kissoon

Edited from a version published on The Mosquito”: http:// gtmosquito. com/ the-coil

Vidyaratha Kissoon lives in Guyana. He is a member of the Amar Deep Ramayana Sangh, a group which sings Ramayana in the traditional baani style, and Chowtaals.”

The 2016 Phagwah season started on Friday 12 February with the planting of Holika Many Hindus would have started the chowtaal sessions which characterise the Phagwah season.

The 2016 Phagwah season started on Friday 12 February with the planting of Holika Many Hindus would have started the chowtaal sessions which characterise the Phagwah season.

Chowtaals are usually sung by groups of people. The rhythm tends to start slow, then increase to a high speed. The upbeat energy is maintained by jal and dholak. Chowtaals are accompanied by ulaara, kabinta, bartaals, yogiya and other styles of songs. Most of the chowtaals originated in India, and are prayers and relate to the stories from the Hindu scriptures.

This 11th Feb 2016 was the hundredth anniversary of a book of Phagwah songs – chowtaals, ulaara and kabinta – written by an indentured labourer.

In February 1916, World War 1 was raging. The Daily Argosy of that time reports that East Indians in La Grange had heard rumours that there was a German cruiser ‘outside the bar’. Magistrate John Brummel had to reassure East Indians at La Grange that their savings were okay in the Post Office Savings Bank and warned them that ‘thieves, coolies and blackguards were waiting to steal their money”.

In February 1916, Pancham, an East Indian from Mahaicony was in court for causing bodily harm to Sumeroo. Biptee and Soogeah, two East Indian women were charged with adulterating their milk. Madbarakh and Jakub Meah were in court for attempting suicide. Jakub Meah was sentenced to 2 months imprisonment with hard labour.

Etwareah and her ‘minor daughter’ Rajwanteah were suing the Demerara Railway Company for $6,000.

However, there is not much news of the cultural life of the East Indians at the time. Ramchiratar Maharaj of Sheet Anchor village, Canje had concluded a “feast” lasting several days at which Harrylal Maharaj officiated at prayers and over 300 poor people were ‘entertained’. A team of East Indians from Port Mourant were planning to play against a team of 7 East Indians and others from Providence at the Queenstown cricket ground

The Argosy Company advertised “Forbes Baital Pachise”and “Pincotts Hindi Manual – “Books required for Hindi examination”.

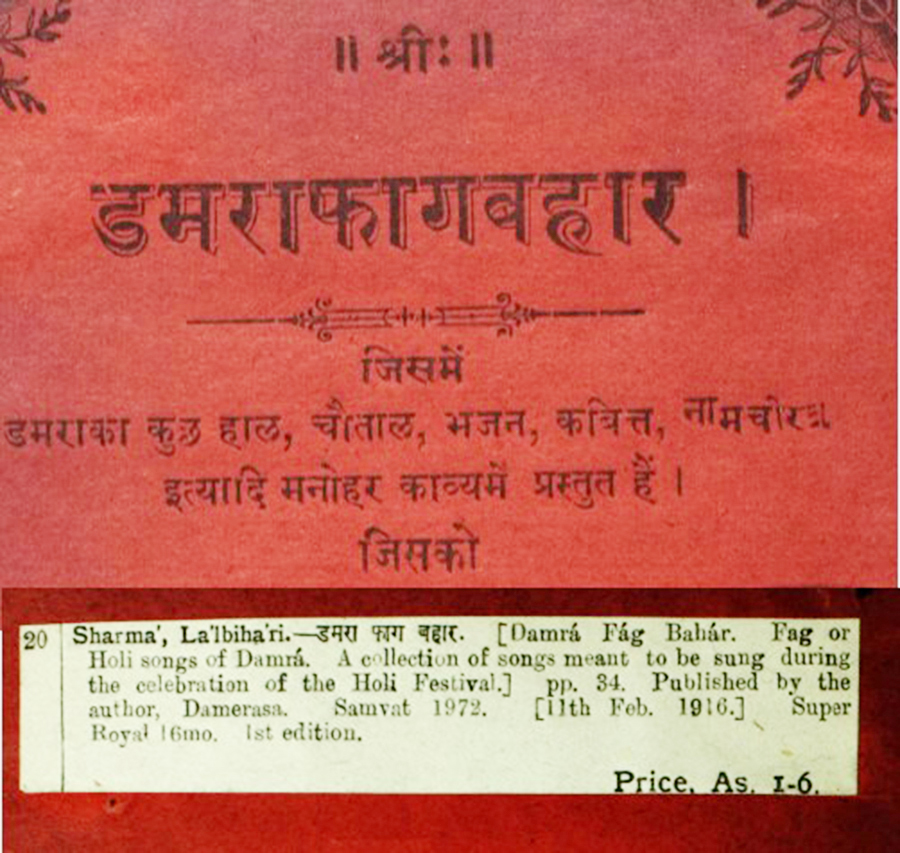

11 February 1916 is the date of publication of Lal Bihari Sharma’s Damra Phag Bahar – Phagwah/Holi Songs of Demerara. The book was published in India. It was written in the Devnagri script. A copy is in the British Library.

In “The Politics of Representation in the Indian Labour Diaspora: West Indies, 1880-1920,” Dr Prabhu Mohapatra writes that Lal Bihari Sharma describes himself as an indentured immigrant living in Plantain Golden Fleece on the Essequibo Coast. Lal Bihari Sharma is not happy about the conditions. He was a Brahmin who had become a labourer. The book of poems includes warnings about the situation of the indentured immigrants. The poetry includes the stories of Rama, Seeta, Krishna, Radha and their joy at playing Holi.

On Phagwah Day, 2013 – Gaiutra Bahadur published a blog “of play and longing: Holi Songs of Demerara”. She explains Lal Bihari Sharma’s work and concludes that Phagwah for the indentured immigrants was about play, and also about longing – for the divine, and also for home. She referred to Lal Bihari Sharma’s work in her recently published book, Coolie Woman.

Sakhi Uti Kar – Lal Bihari’s work comes to life

In 2014, Amar Ramessar was concerned that the music around the 175th celebrations of Indian Immigration still seemed to be about imports. He read the translation obtained by Gaiutra Bahadur of one of the chowtaals. He read the meaning and decided that the ghazal format was more appropriate. “I realised that Sharma referred to himself, just like how the Sufi poets did in their music.”

Amar Ramessar learned to play dholak and to read Hindi from his father, who in turn learned music from his father and god father. He came to appreciate ghazals and has become an accomplished singer. “I started composing using Raga Darbari, but realised it would not work. The final composition used a mix of ragas – mishra raga”

Tarun Deodat who played the tabla is also a third generation musician. His father and father’s father were musicians, and on his mother’s side, there are two taan singers. He learned to play from his father and played with the Sai Baba centres in a bhajan style.

Amar Ramessar and Tarun Deodat both enhanced their training at home with formal training available through the Indian Cultural Centre in Georgetown, Guyana.

They have not studied music in India.

Avinash Roopchand played the keyboard and did the sound engineering for the song. He too is a third generation musician. His parents, Bappi Roopchan and Celia Samaroo are both well known musicians who founded Shakti Strings Orchestra. Bappi Roopchan’s father was a singer .

The resulting Sakhi Uthi Kar was published on Youtube on 5 May 2014 (it can be seen at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mhCQA7AYwbc). The media in May 2014, as in at in the time of the 100th anniversary of Lal Bihari Sharma’s Phagwah songs, had more stories of East Indians in conflicts with the law and with each other, than about young East Indians creating anything in Guyana.

In January 2016, Rajiv Mohabir published his translation of “Sakhi Uti Kar” in the January 2016 edition of Asymptote , a literary journal.

“Chautal 3 (translation here is republished with the permission of Rajiv Mohabir and is not to be republished without his permission)

Sakhi, As soon as I wake I dress

as Spring, with armlets,

bangles, and rings. The necklace

around my throat gleams

like my forehead’s bindi.

I sit on the bed and call,

Piya. Piya. Don’t tell me any news

of him, don’t tell me

I’ve wasted my life. My blouse

bursts; my whole body aches

for him. This distance between us

I cannot bear. I am lost.

The papiha bird cries, Piya.

Piya. Hearing this unstitches me.

Lalbihari: “Peace. Peace.”

Rajiv Mohabir was born in England, to parents of Guyanese origin. He learned bhojpuri songs from his aji (paternal grandmother), Gangadai Mohabir. His chap book – na mash me bone (Finishing Line Press 2011) includes a translation of one of the jogiya we sing during the chowtaal sessions :-

“Adh roti dherh karaila, sab jogi milke khanna, adha rat jab jara lage baap! Baap! Chilawe.

Half roti and one and a half karaila, the yogis gather to eat, in the middle of the night, when cold, they cry out o god god “

In doing the translation of Lal Bihari Sharma’s work he wrote that “These songs are Caribbean music and poetry—translating them is a journey into the realm of my ancestors” . This translation is part of a project supported by a PEN Grant.

Amar Ramessar hopes to compose music for another of Lal Bhihari Sharma’s songs this year. He says the challenge with composition in Guyana is that some of the very talented musicians are not always readily available. He has also been asked to work on what he calls a contemporary presentation of one of the other traditional chowtaals.

He and his wife Rena have a group called Indus Voices which aims to preserve and maintain the traditions of Indian music while also breaking barriers and creating new music.

Rena learned music first in a mandir in Essequibo. The older son of Amar and Rena has already started to demonstrate an avid interest in singing and music.

Amar Ramessar believes Guyana has immense possibilities for creating new genres of music. He recalled a meeting with the late keyboard player, Guy Bunbury. “I played the Raag Bharavi on the harmonium. Guy listened and was able to play on the keyboard. I asked him to do some jazz improvisations. Guy then played the most amazing music. He had been formally trained so that he made a difference”

The difference that matters here is the difference from the politics of division and flogging, an approach which instead recognises the potential in honouring ancestors, and in being creative through collaboration and in ways which will nurture all of us in the place which Lal Bihari Sharma yearned to leave.

The collaboration among the descendants of people from India – the author Gaiutra Bahadur, the musicians Amar Ramessar, Tarun Deodat and Avinash Roopchand and the poet and linguist Rajiv Mohabir, working through Guyana, India, the United States and the United Kingdom – is a fine tribute to the memory of Lal Bihari Sharma on the 100th anniversary of his Phagwah songs.