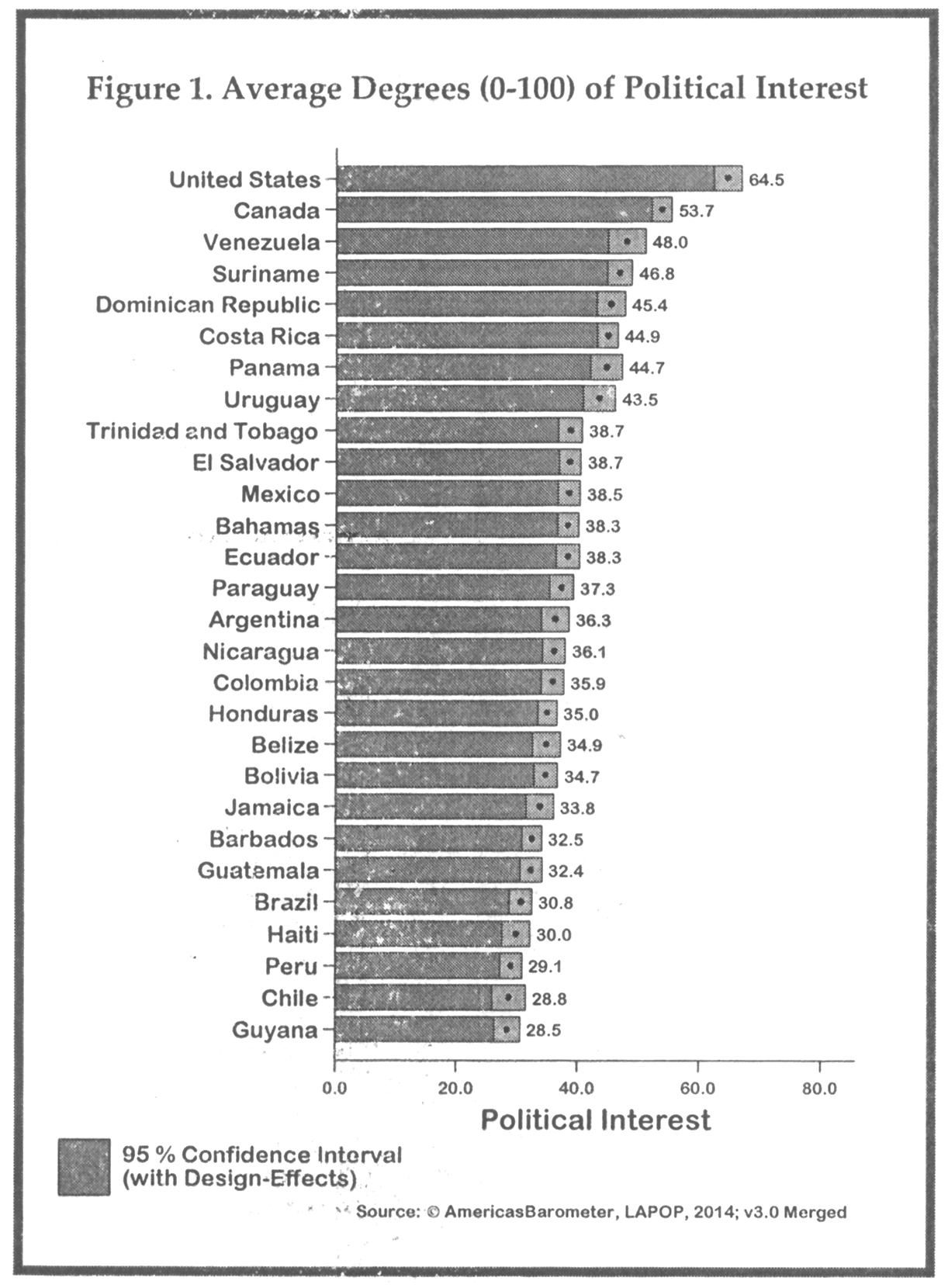

In a survey of political interest in 28 Latin American and Caribbean countries, Guyana placed last with only a 28.5 interest out of a maximum of 100, according to the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP).

The just released report based on the 2014/15 round of the AmericasBarometer survey by LAPOP asked 49,000 individuals in 28 countries the question `How much interest do you have in politics: a lot, some, a little, or none?’

The interest of Guyanese at 28.5 at the lower end of the scale is ranged against 64.5 for the United States with Canada placing second at 53.7. Other CARICOM countries did better than Guyana with Trinidad registering 38.7, The Bahamas 38.3, Belize 34.9, Jamaica 33.8, Barbados 32.5 and Haiti 30.

LAPOP, run by US university Vanderbilt, conducts the AmericasBarometer survey every two years in what has been described as a scientifically rigorous comparative study. The survey measures values, behaviours, and socio-economic conditions in the Americas using national probability samples of voting-age adults.

LAPOP, run by US university Vanderbilt, conducts the AmericasBarometer survey every two years in what has been described as a scientifically rigorous comparative study. The survey measures values, behaviours, and socio-economic conditions in the Americas using national probability samples of voting-age adults.

In a paper entitled `Who is Interested in Politics’, Ariel Helms, Hillary Rosenjack and Kelly Schultz analysed what the figures meant.

They noted that political participation is widely studied for its relevance to electoral and policy outcomes but there are few studies of political interest. The researchers said that the studies that do investigate political interest find that it mirrors political participation.

The researchers found that education, news consumption, Internet use and community participation are strong positive predictors for political participation. Further, the researchers found that those who approve of the President’s/Prime Minister’s job performance report higher levels of political interest. By contrast, those who are dissatisfied show comparatively lower levels of interest.

“There is substantial variation across the 28 countries, with mean values ranging from a low of 28.5 in Guyana to a high of 64.5 in the United States. The region’s longest-standing democracies, the United States and Canada, show the highest levels of political interest, with mean scores of 64.5 and 53.7 degrees, respectively.

“Two of the four countries with the lowest levels of political interest, Guyana and Haiti, are characterized by low levels of development. However, countries with similar political and/or economic challenges are also found higher on the chart. Chile’s low mean value for political interest is surprising, given that it is one of the more developed democracies in the region; yet, discontent simmering in Chile in recent years may have motivated withdrawal by some at the same time that it motivated others to protest in the streets…”, the researchers said.

Asking who is the `Politically Interested Citizen’, the researchers by regression analysis looked at the relationship between political interest and five socioeconomic and demographic factors: years of schooling, wealth, place of residence, gender and age.

Its findings showed that “years of schooling, wealth, and age are all positive predictors of political interest, while being a woman is a negative predictor of political interest. The effect of living in an urban versus a rural area is not statistically significant. All else equal, a maximum increase in wealth (that is, comparing the poorest to the wealthiest quintile) results in a 3-degree increase in political interest. More striking is the fact that, all else equal, a maximum increase in years of schooling (from no education to advanced degree work) results in a 20-degree increase in political interest. This substantial effect of education on political interest suggests that schools can play a key role in cultivating an attentive public. A maximum increase in age results in an approximately 6-degree increase in political interest”.

The researchers said that the results for gender show that an individual who is female declared political interest levels that are 5 degrees lower than her male counterparts, when all other factors are held constant.

“It may be that the barriers to political participation that women face from socialization into particular gender roles (see Batista 2012) manifest into a lower tendency to engage cognitively in politics”, the researchers said.

On the issue of satisfaction with the governing administration, the researchers said that some evidence suggests that those who lose elections respond by expressing negative views towards the executive and, sometimes, withdrawing from political activities like voting. At the same time, the researchers said that other evidence finds that negative emotions, particularly anger, can spur political participation.

“The fact that those who are more critical of the executive are less interested in politics suggests the need to integrate those who disapprove of political actors into political life, encouraging their interest and participation so that the voice of opposition, fundamental to democratic society, is heard”, the researchers said in their conclusion.