Dangerous driving

While restricting minibuses to what in effect are regional routes results in a differentiated market, it does not necessarily result in a differentiated service. Almost all minibus drivers seem to offer the same experience on the road: the risk of death by dangerous driving. One consequence of a segregated market is the competition generated in each market. More time would be needed to obtain realistic data on the demand and supply of the 19 routes. However, one expects rivalry among competitors to be intense. Entry into these markets is relatively easy and substitutes are available to road users. It is not surprising to hear some minibus operators express the view that Route 45, the hospital route, is overcrowded. The area represents an estimated one square mile and is assessed to have between 300 to 400 minibuses accessing that route.

While restricting minibuses to what in effect are regional routes results in a differentiated market, it does not necessarily result in a differentiated service. Almost all minibus drivers seem to offer the same experience on the road: the risk of death by dangerous driving. One consequence of a segregated market is the competition generated in each market. More time would be needed to obtain realistic data on the demand and supply of the 19 routes. However, one expects rivalry among competitors to be intense. Entry into these markets is relatively easy and substitutes are available to road users. It is not surprising to hear some minibus operators express the view that Route 45, the hospital route, is overcrowded. The area represents an estimated one square mile and is assessed to have between 300 to 400 minibuses accessing that route.

About 11 per cent of the passenger vehicles on the road are minibuses. Many of these buses operate within a 12-hour window that coincides with the demand for transportation to get to and from work, school and to conduct business. Some industry insiders believe that the competition in the minibus industry intensified after the closure of the LBI Estate in 2003 and again after the closure of the Diamond Estate in 2011. There is a fear in some parts of the industry that the same thing will happen following the closure of the Wales Estate. One cannot prove the assertions of concerned industry operators. Yet, one cannot ignore the observed trend in vehicle purchases in the period following the estate closures as seen in the following table.

Vehicle purchases

In the first year after the closure of the LBI estate, minibus purchases increased by 21 per cent in 2005 and expanded even more in subsequent years. The data in the index of vehicle purchases indicates that the competition in the minibus market however would not necessarily have come alone from a growth in minibuses purchased. It might have come from an increase in unfair competition from operators of private cars.

The increased competition on some routes is extremely fierce and produces dangerous driving habits. Industry insiders identify ‘hotplaters’ as the worse type since they do not conform to any of the rules of the industry. Hotplaters are always on the move and do not enter the minibus park. They escape paying the parking fees and take advantage of wireless technology to stay ahead of enforcement officers and to seize payload opportunities spotted or rounded up by an assistant. Hotplaters use nimbleness to gain a competitive advantage. It has converted touting into a sophisticated art.

Movement of cargo

The other component of the road transport market is that which deals with the movement of cargo. As with the passenger transport market, data collection on the cargo transport market was difficult. But experience and observation enable one to know that the cargo market is multifaceted. The type of equipment used in the cargo market is determined by the type of cargo being transported. Some cargo can be general such as shoes, clothes and paper. Others could be highly specialized such as fuel, milk, ice-cream and fish. The equipment needs vary. Guyana has dry goods vans or cargo vans. It has open top vehicles like the canter and sand truck. It has flatbeds and it has tank trailers which are used to fetch fuel. It also has refrigerated vehicles and some that are described as ‘high cube’. For the purpose of this article, the various types of vehicles used in cargo transport in Guyana would be referred to as motor carriers.

Motor carrier market

The motor carrier market is differentiated by the type of product being transported and each market carries its own condition of supply and demand. The demand for specialized motor carriers might not be as great as the demand for carriers needed to move non-perishable cargo. As such, supply and demand of transport in the cargo market cannot be generalized. It is important to point out here that some minibuses are used in the cargo market, but that is an insignificant amount. The minibus as a mover of cargo is important on long-haul routes, particularly those of 72, 73 and 94. These are the Mahdia, Bartica and Lethem routes. The minibus is not intended to carry cargo, and even though it could carry a limited amount, represents a dangerous alternative to the larger vehicles built for that purpose.

Inland service

Because of population distribution, most of the transport system in Guyana is designed to provide inland service. As a result, it can be argued that motor carriers have the monopoly over cargo transport service in the coastal areas of Guyana, and except for attempts to service parts of the hinterland, the motor carriers represent the best mode of transportation between most built-up areas in the country. The production structure of the country has contributed to the dominance of the motor carrier over other modes of domestic transportation that are used to move cargo. Guyana, for most of its history, was a predominantly agricultural economy. It exported most of its major agricultural and forestry products, namely rice, sugar and timber. Even where agricultural produce was not being exported, there was a need to get it to domestic markets. As such, Guyana spent more time building roads that made it possible to get produce from the farm to domestic markets or points of export.

Like elsewhere, the pervasive use of the motor carriers is linked to the benefit of accessibility and speed. It is easier to make far more deliveries with motor carriers than with boats and airplanes. Motor carriers do not need special features like water, rail and air transport do in order to facilitate movement of goods. More often than not, the motor carriers are needed to deliver goods to points to be used by other modes of transport and to be picked up at the delivery end. Consequently, motor carriers are often easy to use between most pickup and delivery points. In fact, motor carriers are usually regarded as the universal coordinator between the several modes of transportation.

Interesting feature

A particularly interesting feature of the motor carrier service in Guyana is the relative lack of terminals or warehouses used by carriers. Most motor carriers use the shipper’s location for loading and the consignee’s location for unloading cargo. This feature helps to keep costs low. It also presents a problem for other road users. It is not uncommon to see motor carriers lined up at the side of the road waiting to sell, collect or discharge cargo. Sometimes they block the vision of other motorists and present them with an unnecessarily dangerous driving hazard.

This foray into a discussion about the transport industry in Guyana was premised on the belief that it would have been easier to gather information about the various markets that make up the sector. But the breadth and depth of distinction within the sector required too many definitions and distinctions that our undeveloped record-keeping system does not accommodate. It has become necessary to use several more weeks of research to obtain more information. Yet, it was possible to glean that the industry exhibited many of the social and political tendencies of Guyana.

Restraint on freedom of expression

One example of that attitude is the special restraint placed on the freedom of expression of transport operators in Guyana. Minibus owners, for example, are not permitted to print a name on the bus or to advertise anything other than what is sanctioned by the government. There is therefore no long-term advertising on the minibuses. The minibus market therefore cannot be distinguished by a brand. This restraint causes every minibus operator to be tarnished with the same brush.

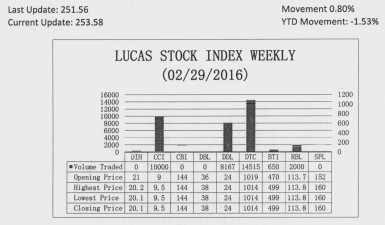

The Lucas Stock Index (LSI) increased 0.80 percent during the final period of trading in February 2016. The stocks of five companies were traded with 35,332 shares changing hands. There were three Climbers and one Tumbler. The stocks of Caribbean Container, Inc. rose 5.56 percent on the sale of 10,000 shares. The stocks of Guyana Bank for Trade and Industry (BTI) rose 6.17 percent on the sale of 650 shares while the stocks of Republic Bank Limited (RBL) rose 0.09 percent on the sale of 2,000 shares. At the same time, the stocks of Demerara Tobacco Company (DTC) fell 0.49 percent on the sale of 14,515 shares. In the meanwhile, the stocks of Demerara Distillers Limited (DDL) remained unchanged on the sale of 8,167 shares.