Conclusion

Never easy

Given the experience and frustrations over the years, many in the Caribbean are surprised that Caricom was able to see 43 years and seemed poised to, and capable of, reaching its golden jubilee in seven years. The path was never easy and Caricom can point to numerous achievements, including in the area of functional cooperation for which it deserves kudos. It has added new members and has increased its cooperation with others since its establishment. Progress is evident in the area of education and disaster preparedness. The region appears to respond to every institutional crisis that has fixed it over its chequered life with the establishment of one form of committee or another.

Given the experience and frustrations over the years, many in the Caribbean are surprised that Caricom was able to see 43 years and seemed poised to, and capable of, reaching its golden jubilee in seven years. The path was never easy and Caricom can point to numerous achievements, including in the area of functional cooperation for which it deserves kudos. It has added new members and has increased its cooperation with others since its establishment. Progress is evident in the area of education and disaster preparedness. The region appears to respond to every institutional crisis that has fixed it over its chequered life with the establishment of one form of committee or another.

Despite the progress, doubts linger about the ability of the integration movement to sustain itself into the distant future. The concern arises from what appears to be the failure of the movement to create and solidify the foundation for its long-term independent survival. The essential concern is about the difficulty that the region is experiencing in developing and expanding its production, finance and knowledge structures after nearly 50 years of trying. These are the three areas in which progress is needed to expand opportunities for, and achieve greater involvement of, the people of the region. They are required to deepen and intensify the integration movement and to justify keeping the faith in the philosophy that underpins integration efforts. The focus of the rest of this article will be on the production structure, particularly as it relates to cross-border trade. Data on investment flows is hard to obtain and as such cross-border investment flows will not be discussed here.

Bedrock

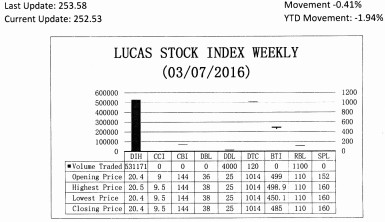

The Lucas Stock Index (LSI) remained unchanged during the second period of trading in March 2016. The stocks of four companies were traded with 536,391 shares changing hands. There were no Climbers or Tumblers. The stocks of Banks DIH (DIH), Demerara Distillers Limited (DDL), Demerara Tobacco Company (DTC) and Republic Bank Limited (RBL) remained unchanged on the sale of 531,171; 4,000; 120 and 1,100 shares respectively.

The bedrock of the integration movement is the production structure. This is the sphere of activity that determines what is produced, how it is produced, by whom it is produced, for whom it is produced and under what terms it is produced. The finance and knowledge structures aid in this process of determining how the goods and services are produced and under what terms and conditions they are produced. With the formation of the Caribbean Community and Common Market came expectations that the economic activities among member countries would increase rapidly and bring benefits to people living in the member countries. It is the virtue of liberalism, that economic philosophy that champions the merits of markets, free trade and liberty for all. The struggle for economic independence eventually took all the countries of Caricom to the altar of liberalism. Some were helped with packages of structural adjustment from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) while others bought into the wisdom of the market and the value of liberty on their own volition.

Dreams of integration

It was to the market that all the countries of Caricom turned once again to realize the dreams of integration. By 1989 when Guyana started implementing its economic recovery programme, uncertainty had given way to realism. An energized Guyana held the potential for increased demand for products from the Caribbean. The theory of comparative advantage helps to determine what is produced and by whom it is produced. Guyana was thought of once again as holding the key to the food security of the region through the vast agricultural potential of the country. Any progress in agriculture was expected therefore to come from Guyana. The liberal economic policies of Guyana and the rest of the region gave rise to the belief that the market would allocate the scarce resources of the region responsibly. Market demand and prices determine who gets the goods and services that are produced. It was felt too that the market would distribute a substantial amount of the production of the region within the region.

Where Caricom was concerned, the production structure was also assessed by the level of trade between member countries. Greater amounts of trade often signal growing economies which are reflected in higher levels of real gross domestic product. The greater the amount of trade, the stronger the economies are expected to become. Stronger economies lead to a deepening of the Caribbean integration movement. And so it is the state of trade among member countries that creates angst among many in the Caribbean, especially among those persons who are rooting for the success of the movement. A review of trade among Caricom countries over the period 2005 to 2014 helps one to understand the reason so many remain pessimistic about the future prospects of the regional integration movement.

Economic capabilities

Before proceeding further with the discussion on trade relations among Caricom countries, it would be useful to point out that the regional movement usually recognizes the difference in economic capabilities among member states. Belize, Haiti and the island countries that make up the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) are referred to as the less developed countries of Caricom. The countries in this latter grouping are Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, St Kitts and Nevis, St Lucia, and St Vincent and the Grenadines. On the other hand, the five larger economic states of Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago are referred to as the more developed countries. The other point is that the trade data discussed herein does not include Haiti.

Size of trade

Intra-Caricom trade, measured as the average of imports and exports, was reported at US$2.8 billion in 2014. Over the 10-year period 2005 to 2014, the size of the trade is calculated as US$2.9 billion. The best years for the trade were 2008, 2011 and 2013 when in each of them trade exceeded US$3.2 billion. The bad years were 2007, 2009, 2012 and 2014 when the size of trade dipped below the period average of US$2.9 billion. The worst year for intra-regional trade was 2009 when the trade dropped 42 per cent. Intra-regional trade grew by two per cent over the period and, at that rate, does not give much comfort to anyone either.

The distribution of the trade between the more developed countries (MDCs) and the less developed countries (LDCs) of Caricom is an additional indicator of the limited integration among Caricom states. The MDCs account for 87 per cent of the intra-Caricom trade while the LDCs account for 13 per cent of the trade. The largest contributor to the trade was Trinidad and Tobago which was responsible for 39 per cent of the trade. It is followed by Jamaica with 17 per cent of the intra-regional trade. Barbados accounts for 11 per cent while Suriname controls 10 per cent of the trade. Guyana is the smallest contributor from among the larger grouping of Caricom members with an average of nine per cent of the intra-regional trade from 2005 to 2014.

When the data is disaggregated between the value of exports and imports, it becomes a whole new story. It shows the lopsided nature of trade. It also shows that the production structure of the region still does not cater for market demand from the region. The five MDCS account for 93 per cent of exports while the LDCs account for seven per cent. The biggest exporter among the Caricom countries is Trinidad and Tobago. It accounts for 73 per cent of the value of the goods that go to other Caricom countries. The remaining 14 member countries account for 27 per cent of the exports. Reasonable contributions are made by Suriname which accounts for eight per cent of the value of the exports, Barbados which accounts for five per cent while Guyana and Jamaica account for four and two per cent respectively. This means that Belize and the remainder of the LDCs contribute less than two per cent each to the intra-regional market. The overall conclusion from all the data is that most of the production undertaken in the region is sold outside of the region.

Burden of integration

While Jamaica is among the set of countries that send most of their produce outside of the region, it is the one that buys most from the region. Jamaica is the largest importer of goods from Caricom countries, accounting for one-third of the goods and services traded among regional countries. Jamaica’s spending is twice that of Barbados and Guyana, nearly three times that of Suriname and almost seven times that of Trinidad and Tobago. Jamaica spends much of its money in the region, but is unable to look to a regional finance structure to support its spending. It is interesting to note that Trinidad and Tobago sells the most to the region, but is among the countries that buys the least from within the region. Even St Lucia with seven per cent of the import trade buys more than Trinidad and Tobago. This either means that Trinidad and Tobago produces similar goods to those which the rest of Caricom produces or it prefers to buy goods and services produced outside of the region. If the former situation is the case, then the issue of complementarity seems to be downplayed by the exporting giant of Caricom. If it is the latter, then the burden of integration becomes more difficult to bear.

Right systems

Guyana’s trade with Caricom has been growing at an annual rate of six per cent over the review period and so has Suriname’s. This growth rate is three times higher than the regional average and indicates that both Guyana and Suriname offer significant potential for the expansion of regional trade. On the other hand, despite being the largest importer of Caricom products, Jamaica’s trade with the region has remained flat and even showed signs of declining over the period under consideration. The narrow range of products and the mixed performance of member countries in regional trade show that there is scope for Caricom countries to expand trade. Guyana, for example, needs to put the right systems in place in order to convert the single market into a national asset.