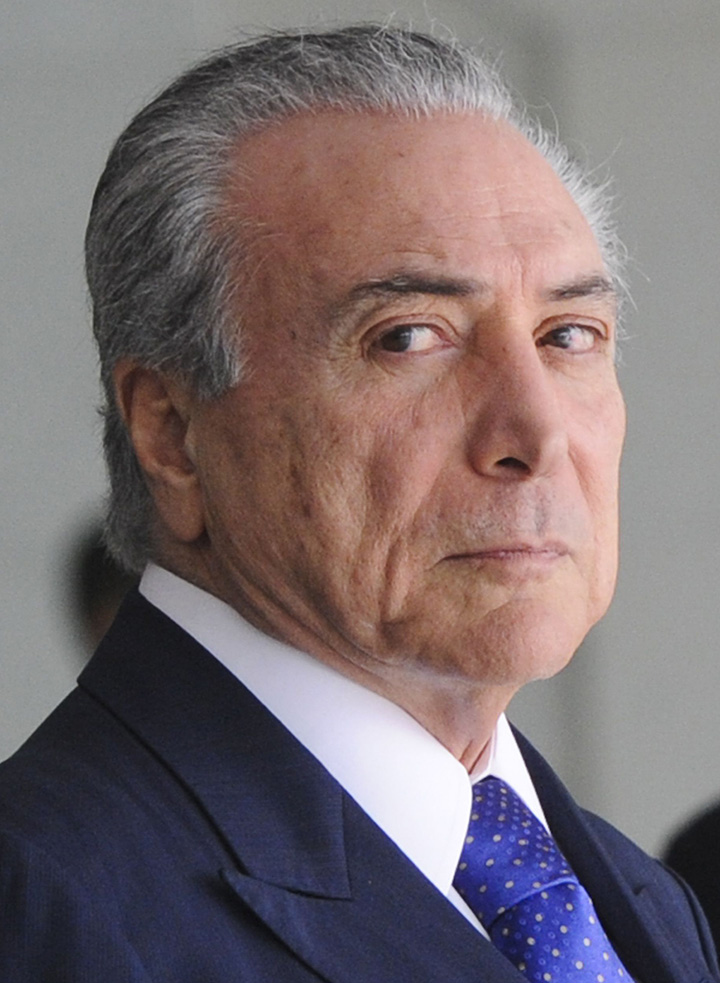

BRASILIA, (Reuters) – A Brazilian Federal Supreme Court justice yesterday ordered Congress to start impeachment proceedings against Vice President Michel Temer, deepening a political crisis and uncertainty over leadership of Latin America’s largest country.

Justice Marco Aurelio Mello told the lower house to convene a special committee to consider the ouster of Temer over charges he helped doctor budget accounting as part of President Dilma Rousseff’s administration.

Another committee is already analysing similar charges against Rousseff, a leftist who is scrambling for support to defeat an impeachment vote in the lower house as early as mid-April.

Although the unprecedented decision can be overturned by the full supreme court, Mello’s ruling raises questions about future governance of a country mired in political turmoil, an economic recession and an institutional crisis increasingly being handled by Brazil’s judiciary.

Because Temer is next in line for the presidency if Rousseff were impeached, the possibility of his ouster complicates the calculation that lawmakers must make if they vote to oust Rousseff. If one is guilty of the charges, the ruling suggests, the other is guilty too.

“This takes away some of the momentum for her impeachment,” said Sonia Fleury, a political scientist at the Getulio Vargas Foundation, a business school and think tank in Rio de Janeiro. “Her opponents will now have to rethink their strategy.”

Fleury said it is unlikely that the 11-member court will overturn Mello’s decision.

Brazil’s currency, the real, extended losses following the ruling, frustrating investors who hope a Temer administration would be more market-friendly and pull the economy out of what could be its worst recession in a century.

Lower House Speaker Eduardo Cunha, a party colleague of Temer’s and the third in line for succession, had previously declined to start impeachment hearings against the vice president. Cunha, also embroiled in a scandal over corruption charges related to the kickback probe around state-run oil company Petrobras, could appeal the decision, according to local media reports.

The prosecutor who first accused Rousseff of breaking the fiscal responsibility law has said that Temer should not be blamed for the government’s fiscal manoeuvres.

Temer yesterday stepped aside as the head of the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party, the large, ideologically amorphous party that until last week was the main coalition partner for Rousseff’s Workers’ Party. By stepping down, analysts said, Temer can avoid responding to attacks against the party for leaving the coalition.

“Temer is trying to distance himself from the party to avoid being accused of influencing political decisions aimed at destroying president Rousseff,” said Augusto de Queiroz a political scientist with Brazil’s congressional research service.

One of Temer’s closest allies, Senator Valdir Raupp, said on Monday that Congress should call for new presidential elections to end the political impasse. Others have echoed the suggestion.

Yesterday, Rousseff made light of the possibility, suggesting lawmakers themselves agree to end their terms early. She also rejected calls for a cabinet reshuffle to help her muster political support against an impeachment vote.