By Cynthia Barrow-Giles

Cynthia Barrow-Giles is Senior Lecturer in Political Science at the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus, Barbados. She also writes a weekly column, “Imagine that! Reflections with Cynthia Barrow-Giles in Barbados Today, where this previously appeared.

You might think that Caribbean politicians will take a leaf from transitional, well established and newer democracies in regulating the flow of money into the political system. Alas no! For we are doing so well on global indicators that even those who dare to raise any issue pertaining to corruption and abuse, are told that we are descending into stupid noises. This week I will continue my descent by focusing on one of my favourite topics, the controversial and dreaded issue of political party and elections campaign financing, in other words, political money. It is impossible to deal with the range of issues that political money deserves, nevertheless I will attempt to tackle a few of the critical aspects.

You might think that Caribbean politicians will take a leaf from transitional, well established and newer democracies in regulating the flow of money into the political system. Alas no! For we are doing so well on global indicators that even those who dare to raise any issue pertaining to corruption and abuse, are told that we are descending into stupid noises. This week I will continue my descent by focusing on one of my favourite topics, the controversial and dreaded issue of political party and elections campaign financing, in other words, political money. It is impossible to deal with the range of issues that political money deserves, nevertheless I will attempt to tackle a few of the critical aspects.

Democracy thrives on competition and elections constitute the cornerstone of democratic governance. By undermining competitive elections, campaign finance laws or lack thereof undermine democracy. Equally important is the fact that campaign finance can control the political process. Regulations on campaign finance are therefore seemingly designed to engender equity and equality and to prevent corruption or the appearance of corruption in the political process. Consequently, typically modern campaign finance regulations place limits on the methods used by candidates and parties to obtain contributions whether from firms, individuals and foreign governments, the size of those donations, whether those contributions are anonymous or not, gender balancing, access to State financing, use of government resources, access to the media, reporting lines, sanctions and the way in which political monies are spent in pursuit of electoral success and hence governmental power.

With respect to contribution limits in member states of the Commonwealth Caribbean, only Antigua and Barbuda up to 2015 had such restrictions and these were clearly inadequate. Globally such limits on contributions to candidates are designed to ensure a fair campaign playing field among political combatants. Now of course we instinctively know that unless national sentiments take a dramatic turn, it is difficult for a challenger to defeat an incumbent unless the former spends at least as much as, and probably more than, the latter during the campaign period. This is especially so in a context where the political party which provides the candidates with a political platform lacks a historical stance on which to build a support base. Inevitably therefore, newer political parties and their candidates face huge difficulties in any election context which tends to favour the more traditional and dominant political parties. Many political scientists writing on the issue argue that it is perhaps only by spending large sums on television and newspaper advertising, direct mail solicitations, an attractive social media platform and a small army of paid canvassers, that a challenger can develop the levels of name recognition, and voter mobilization needed to contend with the dominant political parties and their hegemony of the system. That is unless you already have a national profile.

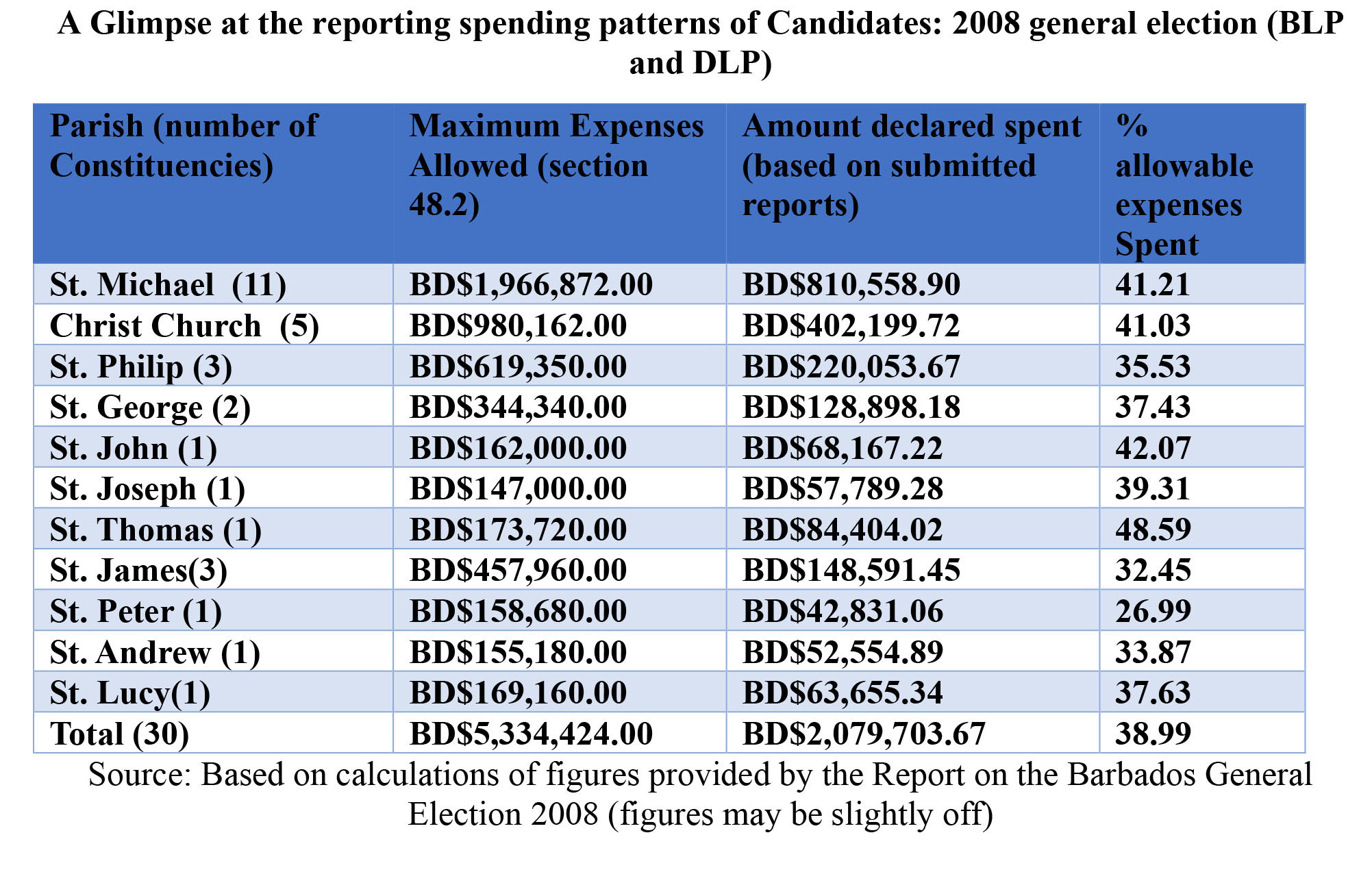

Let us take the example of Barbados. What are the paltry existing laws on campaign finance and spending under which the last election was waged? The Representation of People Act provides for each candidate to spend up to BD$10.00 per elector. Notably, the Act is silent on political parties, which is not surprising as political parties are not recognised under the Constitution. Further the Act specifies the time frame within which the political candidates are expected to submit their report on their finances to the Elections Commission. How many people in Barbados read those reports? I would venture to hazard a guess that perhaps a tiny fraction of the population does. The report of the Elections Department on every general election makes for interesting reading. And given my interest in the area I have taken a critical look at these reports to assess what is actually being reported against what the naked eye reveals about the level of spending at elections in this country. No surprise there, it is a paltry sum indeed and surprise, surprise, far less than what legally each candidate is legitimately empowered to spend. The 2008 elections in Barbados were no doubt keenly contested elections in which a newly organised Democratic Labour Party under the leadership of David Thompson sought to regain control of parliament and therefore assume the leadership of the country from a determined Barbados Labour Party led by Owen Arthur. In that election Barbadians observed the use of new technologies, electioneering strategies, high levels of advertising on the part of both political parties and electioneering paraphernalia on a scale perhaps not previously seen. What was declared by the candidates? The table below provides a summary of reported spending by all the candidates (There was no reporting by three independent candidates. Please do not get caught up in my calculations; it is the larger point that I wish you to grasp).

We know that far, far more was spent on the elections. But the existing law has a notable gap. It does not demand of political parties any disclosure requirement. So we are told that money spent is acquired through cake sales and car washes. But we know better and indeed a few businessmen are now sounding their voices to the call for regulation of the system. Why is this important? Because political parties are highly dependent on private sources of finances, notably from big business. And we need to know what these companies get in return for their financial support. The government manages a huge portfolio in terms of contracts and the procurement system is of immense importance. In Jamaica for instance, following the 2011 general elections six (6) firms publicly disclosed (the then existing laws did not require this) that they had contributed some J$69 million (approximately US$630,000) to the two major political parties. Whilst this is of immense value, it was reported that about J$1 billion was spent on the elections, much more than what the candidates were legally allowed to spend.

Now what of foreign government involvement in the politics of Commonwealth Caribbean States especially in the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS)? In my many election observation missions with the OAS and the Commonwealth across the region, the various teams have been told of foreign monies entering the system on an unprecedented scale. Certainly, from time to time in Barbados we heard of Taiwanese contributions to parties, in Guyana it was Jewish contributions (not from the State of Israel), in the OECS it was Venezuela and Taiwan in particular. Noted Caribbean journalist Rickey Singh thus spoke of “dollar diplomacy” and ‘energy diplomacy”. In St. Lucia, observation teams were informed of US$1-2 million contributions to individual parliamentarians from 2006-2011 by the government of Taiwan; monies which were ‘gifted’ to these parliamentarians without the benefit of being deposited into the consolidated fund where perhaps some oversight may have been proffered. A forensic audit initiated by Prime Minister Kenny Anthony following the St. Lucia Labour Party’s victory at the polls in 2011, of some of the constituencies where such money was ostensibly being used for community based projects, revealed the level of naked abuses, sleaze and general corruption associated with such funds.

I am however hopeful. The signs are there. Jamaica, which has a long history of clientelism and corruption after corruption scandal concerning Ponzi schemes, contributions of Dutch funds to parties and drug money entering the political system became the first Commonwealth Caribbean country to legislate a tough political money regime. This was the combined result of a number of things: the near collapse of the State in 2011; the demise of Prime Minister Bruce Golding; the defeat of the Jamaica Labour Party after a single term in office by the Portia Simpson led People’s National Party, in combination with a progressive and forward thinking Elections Commission working closely with experts from the OAS and Commonwealth, and a vibrant campaign orchestrated by the well known activist and political scientist, former senator and political leader Trevor Monroe and his National Integrity Action. Of course we ought to weigh the value of overly regulating the campaign activities of political parties in the interest of transparency and anti-corruption against its cost to competition. But the sounds of protest can be heard on social media and it will continue, the sound of frustration by sections of the business community, trade union movements and other interested persons have begun and it will not abate, even though Barbados is described as a ‘model democracy.’

Though there is so much more left to say on this issue, I end with a reference to the view of Trevor Munroe from Jamaica, who has insisted that across the region radical reforms are required to build institutional capacity, to strengthen anti-corruption laws, anti-corruption institutions and integrity building capacity and that there is an urgent need to deal decisively with political party registration and campaign financing disclosure. He continues that “the consequences of continued failure in these regards are grave and serious. First of all in regard to economic growth, the increased levels of poverty and in the intensification of the burden on the backs of the poor who suffer the most when scarce resources are diverted away from development into the pockets of the corrupt.”

These sentiments were echoed in an excellent guest column article written by Peter Laurie and which appeared in the Barbados Today published on Tuesday April 07, 2015 on bolstering Barbados democracy in which among other things, he argued that Barbados “desperately needed campaign finance reform”.

But “one and one is not two”! Imagine that! Let’s make some stupid noises.

“Blow the dust off the clock. Your watches are behind the times. Throw open the heavy curtains which are so dear to you – you do not even suspect that the day has already dawned outside.” (Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn)