PARIS (Reuters) – “Je ne t’aime plus, mon amour” — “I don’t love you any more, my love” — was the wistful song of a love gone cold which greeted devotees of President Francois Hollande as they arrived at a rally for him last week.

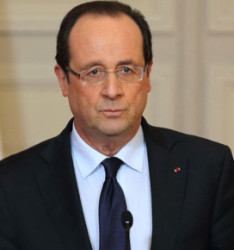

An odd choice to fire up a political gathering, the track nonetheless captured the deeply unloved quality of Hollande’s presidency just as he and his closet backers start to explore whether he has any real chance of a new term in 2017.

Just before he was elected in 2012, Hollande tweeted of the incumbent Nicolas Sarkozy, by then facing broad disenchantment: “Can you imagine five more years with the same?”

Now the same question applies to him. Since coming to power, Hollande has watched his ratings crumble to historic lows over a failure to restore the economy, doubts over his leadership and policy U-turns on security and other policy.

A poll published April 20 by the Viavoice agency found only one percent of voters think Hollande would make a “very good” president if given a second term next year; barely 10 per cent judged that he could be “quite good”.

A steep fall in membership of his Socialist party shows the disillusionment even among allies: the number of members has halved from 173,000 in the year he was elected to just 86,000.

While last week’s gathering in a Paris university building was largely attended by grey-haired supporters, France’s youth have little time for Hollande. Thousands have joined sometimes violent protests against a labour reform he says will encourage hiring but which they fear will make it easier to be sacked.

Polls show many left-wingers who backed him in 2012 won’t this time: Without wooing them back he has no chance. To that end, he has promised more subsidies to students and a pay rise for teachers.

Yet many on the left see the labour reform as a betrayal, the last straw after his 2014 pro-business switch and an attempted security crackdown that was ultimately shelved.