LOS ANGELES, (Reuters) – When Jodie Foster wanted to explore the human relationship with technology and virtual intimacy in her latest directorial effort “Money Monster,” she opted to use Wall Street as her setting and raise the dramatic stakes by holding George Clooney hostage.

“I wanted to see how those things affected these two human beings, in this small little room, who are confined with each other,” she said.

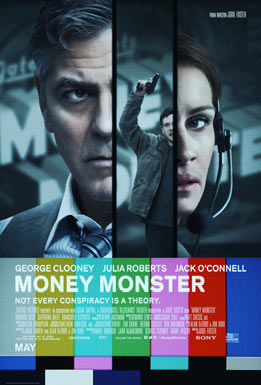

Sony Pictures’ “Money Monster,” premiering at the Cannes Film Festival this week and opening in U.S. theaters on Friday, sees Clooney play Lee Gates, a suave, showboating host of a money news TV program, held hostage live on air.

Gates and his producer Patty (Julia Roberts) are forced by the captor, who lost his life savings investing in stock that Gates had vouched for, to dig deeper into the technical glitch that wiped away millions of dollars of people’s savings.

“George’s disaffected old school journalist has to learn some new tricks, he has to become more of an activist journalist,” Foster said.

The film taps into millennial disillusionment through the captor Kyle (Jack O’Connell), a young man unable to provide for his family, which Foster said “did tap into something, there’s a certain rage of a generation of people.”

“That’s the smack in the face, it’s almost classist in a way, in that we told (millennials) that you could achieve something and actually you’re not going to be able to get a job. That’s enraging,” she said.

“That’s the smack in the face, it’s almost classist in a way, in that we told (millennials) that you could achieve something and actually you’re not going to be able to get a job. That’s enraging,” she said.

While the film presents an American story, the larger social and financial themes of “Money Monster” will resonate around the world, Foster said.

“Europe is going through massive financial crisis … so this isn’t foreign to them. I feel like this feels pretty international, I don’t feel like it’s purely an American film,” Foster said.

“Money Monster” is the fourth feature film directed by Foster, 53, who started acting as a child and has won two best actress Oscars for 1989’s “The Accused” and 1992’s “The Silence of the Lambs.”

Amid the hot button topic over the lack of gender diversity in Hollywood, Foster said things haven’t improved much for female directors over her career, and have been made worse by studios not wanting to take risks in the current economy.

“I don’t know why women are seen as a risk, that’s really the question,” Foster said.

“Forty, fifty years I’ve been working in the film business, why would I be a risk? But it’s gender psychology.”