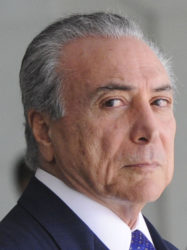

BRASILIA, (Reuters) – Brazil’s interim President Michel Temer said yesterday he would seek constitutional change to limit increases in public spending as part of a series of measures to curb a record fiscal deficit and regain investor confidence.

Temer, a centrist who took over from leftist President Dilma Rousseff two weeks ago after she was suspended pending trial, said the amendment would restrict growth in state spending to the previous year’s inflation rate, excluding debt payments.

Constitutional change requires 60 percent support in both chambers of Congress at a time of bitter divisions following Rousseff’s suspension on charges of breaking budget rules. She vigorously denied wrongdoing.

Temer said the move was the best way to restore Brazil’s credit rating, bring down interest rates and drag Latin America’s biggest economy from its worst recession in decades.

Brazil lost its coveted investment-grade rating in December due to its high deficit. Benchmark interest rates surged to 14.25 percent last year, stifling investment, as inflation hit double digits.

Temer, who was Rousseff’s vice president, will seek Congressional approval for a record deficit of 170.4 billion reais this year, excluding debt servicing, in a sign of the crisis in public finances.

“This will be the first test, for both the government and the legislature, to show Brazilians that we are working,” he told congressional leaders.

Finance Minister Henrique Meirelles, a former central bank governor, said a raft of reforms to be sent to Congress within two weeks was aimed at securing the government’s solvency. Brazil’s overall deficit will top 10 percent of gross domestic product for a second straight year.

To help plug the gap, the state development bank BNDES has agreed to the early repayment of 100 billion reais ($28 billion) owed to the Treasury, Temer said.

The proposed constitutional amendment would reduce the growth of mandatory health and education spending, Meirelles said. There would be a review of government subsidies and taxes could be raised temporarily, he added. More than two-thirds of the Senate and lower house backed impeaching Rousseff, whose popularity plummeted amid the economic crisis. But unpopular spending caps and tax increases at a time of rising unemployment could threaten Temer’s fragile coalition.

“The effectiveness of the new economic team … will depend critically on the degree of political support and the capacity of the Temer administration to build bridges and secure the necessary support in Congress,” Goldman Sachs economist Alberto Ramos said.

Brazil’s currency and Bovespa stock index were little changed on Tuesday, signaling investors were not optimistic the reforms would lead to a quick recovery.

Temer’s proposal to unwind Brazil’s sovereign fund, which holds about 2 billion reais ($563 million) in Banco do Brasil equity, sent shares in the bank lower. Temer also promised rigid rules for executives running pension funds and state companies.

Markets have warmed to Temer’s government, which has vowed a more business-friendly program than Rousseff, but the loss of a key minister to a political scandal on Monday showed the challenges he faces.

Some economists said the new proposals were a move in the right direction but not enough.

“The government has to announce measures that have effect by the end of the year and really increase revenues,” said Alex Agostini, chief economist at Sao Paulo-based Austin Rating. “They cannot get away from raising taxes, and they have to make clear that they will reform the pension system.”

In a rare bit of good news, central bank data on Tuesday showed a current account surplus in April for the first time in seven years, as a weak currency and fragile demand eased reliance on foreign investment. The repayment by BNDES, starting with a transfer of 40 billion reais, will save Brazil 7 billion reais a year, Temer said.

His government is examining the legality of the move after Rousseff was put on trial by the Senate for allegedly using money from the state bank to boost spending.

Temer said reforming Brazil’s generous pension system will be undertaken after developing a national consensus. Unions have strongly opposed changes that would reduce benefits.

The government is also considering whether state oil company Petrobras should be required to hold a stake in subsalt oil reserves.