2016 remains a significant and celebrated year for Shakespeare. It is commemorated worldwide as the 450th year since his death in 1616, and following major and clamorous celebratory events in London and Stratford in April, there are still similar programmes continuing during this year in England and elsewhere, including Guyana.

Guyana would have participated in one of the most ambitious projects in 2014 when the National School of Theatre Arts and Drama (NSTAD) acting for the Department of Culture hosted a visit by the Shakespeare Globe Theatre. This English company set off on a world tour covering two years and some 180 countries performing Hamlet. The project was called “Globe to Globe Hamlet” and set off on Shakespeare’s 400th birthday on April 23, 2014 at the Shakespeare Globe Theatre in London and ended back in the UK on the 450th anniversary of his death on April 23, 2016. They performed in Guyana during NSTAD’s production of the 2014 National Drama Festival in November.

Guyana would have participated in one of the most ambitious projects in 2014 when the National School of Theatre Arts and Drama (NSTAD) acting for the Department of Culture hosted a visit by the Shakespeare Globe Theatre. This English company set off on a world tour covering two years and some 180 countries performing Hamlet. The project was called “Globe to Globe Hamlet” and set off on Shakespeare’s 400th birthday on April 23, 2014 at the Shakespeare Globe Theatre in London and ended back in the UK on the 450th anniversary of his death on April 23, 2016. They performed in Guyana during NSTAD’s production of the 2014 National Drama Festival in November.

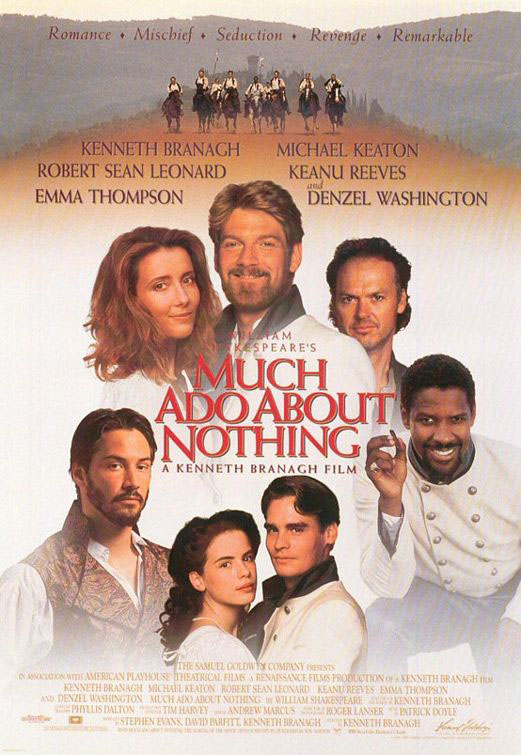

As a contribution to this elaborate series of commemorative programmes, the British High Commission in Guyana revived one of the most perfect of Shakespearean comedies – Much Ado About Nothing (1598). British High Commissioner Greg Quinn and Mrs Wendy Quinn in a programme called “Celebrating Shakespeare” recalled from the archives the second most successful Shakespeare film ever released, Much Ado About Nothing directed by Kenneth Branagh (1993). As a box office success it trails only Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet.

Another point of interest is that it is a BBC film, and the BBC has been at the centre of the 2016 anniversary celebrations of the world’s greatest ever playwright. The British broadcasting giant, a leader in radio and TV worldwide, is known for its films on a large scale for the big screen and on a smaller scale for TV, including serials of well-known works. It is also well known for screen adaptations of prominent novels. Among the memorable productions would be the Jane Austin classic Pride and Prejudice starring Colin Firth, and EM Forster’s Howard’s End with Emma Thompson, who won an Oscar for her role, Anthony Hopkins and Vanessa Redgrave.

Of further interest is that the BBC also converted to television films, West Indian novels, notably Phyllis Shand Alfrey’s The Orchid House and The Humming Bird Tree, a celebrated novel about growing up in a colonial Trinidad divided by race and class by Guyanese-Trinidadian writer Ian McDonald.

Of further interest is that the BBC also converted to television films, West Indian novels, notably Phyllis Shand Alfrey’s The Orchid House and The Humming Bird Tree, a celebrated novel about growing up in a colonial Trinidad divided by race and class by Guyanese-Trinidadian writer Ian McDonald.

Much Ado About Nothing has been around for a long time, but it is one of the outstanding successes among British films. It is actually a British-American film as the BBC collaborated with American filmmakers in its production. It was released on both sides of the Atlantic with much acclaim and wide box office sales. Part of its popularity had to do with the cast which includes Denzel Washington as Prince Don Pedro, Emma Thompson as Beatrice and the director Branagh, who was married to Thompson at the time when the film was made, as Benedick.

The film is an extraordinary work in itself and is a very good selection with which to celebrate Shakespeare for a number of reasons. The play on which it is based is the perfect Shakespearean comedy with all the elements of the form. Added to that it is remarkable what the film does with it as an excellent demonstration of art and of Shakespeare in our time. This is a romantic comedy true to the type, in which “the course of true love never did run smooth”. In the main plot the marriage of the lovers Claudio and Hero is threatened by the malicious scheme of the embittered malcontent Don John. These kinds of complications involving misunderstandings, mistaken identities and villainy are typical of the dramatic form.

So, too, is the villainy. Don John is the characteristic Machiavel (or Machiavellian character) who would wrought evil for no justifiable or logical reason. The type is named after Italian political scientist, courtier, ‘diplomat’, politician and intellectual Machiavelli who was very controversial in his time. His very subversive writings were considered dangerous, were banned and it was an offence to have them in England during Shakespeare’s time. Machiavelli was inherently ruthless and bereft of principles, and so his name was given to villains in the drama who were inherently evil. So is Don John in this play in which he executes a plot to deceive the Prince and Claudio who are convinced they witnessed Hero in an act of infidelity the night before the wedding. This causes them to disgrace her before all assembled for the wedding. Again, true to the type, this led, not only to injurious slander, but to near tragedy. It causes Beatrice to push Benedick to “kill Claudio”, resulting in a challenge to a duel that could have ended in death and further tragedy. But in this formula of the Shakespearean comedy, tragedy is averted at the end and there is a satisfactory resolution and happy ending.

This is brought about by another typical character – the provider of comic relief, the humorous character Dogberry the Constable. When tragedy looms and the dramatic atmosphere is tense and heavy, comic relief is provided by characters of Shakespeare’s innovation who are written in to amuse the audience, often with low comedy if not outright farce. Shakespeare did indulge in slapstick to relate to an audience that loved it. Constable Dogberry and his watchmen in their stumbling, bungling fashion, discover the plot and arrest the villains, thus saving Hero’s reputation and averting the threatened tragic end to the play.

Yet another significant dramatic characteristic is the sub-plot – the romance between Beatrice and Benedick. It is a mark of the playwright’s genius the way he sets up matches of this type between characters who start out publicly loathing each other while being secretly in love. They are the intellectual life of the play, providing most of the wit, the mental substance and the very entertaining high comedy in the drama.

It must be pointed out that these factors characterise Much Ado About Nothing and make it a perfect example of its type. But they are outstanding features, only typical because they demonstrate Shakespeare’s genius. He was the one who took the standard classical comedy inherited from the Greeks and introduced his own innovations to the point where the term “Shakespearean Comedy” came into use.

Then, to double the experience for the modern audience, Branagh turned the film into a brilliant demonstration of Shakespeare in our time. It is clearly Shakespeare, yet it is a modern film that makes Shakespeare delightfully easy to digest. It is at the same time classical, faithful to its source and its age, and a work of twentieth century post-modernism. It is an art film that, we are told, did well at the famous Cannes Film Festival, while at the same time it was hugely popular as a big screen movie, making US$36 million, well above its budget of $11 million, according to the sources.

A most extraordinary achievement of the film is its language. It is fast moving, sustaining a hectic pace, even in rendering the longest and most complex speeches. The actors have an accomplished command of Shakespeare’s dialogue, delivering both those lines in prose and those in blank verse without distinction. Whatever else Branagh did, he was faithful to the original language, yet the actors delivered it in the rhythms of modern English easy to understand.

The setting remains Messina (Renaissance Italy), vividly played out in such sequences as the dinner party. Yet the costuming is one of the post-modern features of the film. While being casual, it does not distract from the time and setting and one still gets a strong sense of place. The film makes the landscape neutral; nothing jarred, one could hardly tell if it were mediaeval, Elizabethan or modern.

There are many modernistic impositions of images, symbols and inset sequences that are definitely artistic enhancements. Almost ironically, there is also the use of much realism. One inescapable example is the extremely steamy encounter between Borachio and Margaret, deliberately staged to deceive the Prince and Claudio. In the original play it is all verbal description, there is no physical display, but Branagh’s rendition is sexually graphic, with the effect that it was no doubt a damning verdict against Hero for any who witnessed it. There would be no escape or excuse for a woman caught in that voracious embrace.

The film is overflowing with energy and intensity, as in Claudio’s rage when he aborts the wedding ceremony, or Benedick’s threatening challenge to Claudio, or Beatrice’s venom in persuading Benedick to rise to the vengeance for the slander against Hero. The film is thoroughly successful even to the comic relief. The portrayal of Dogberry by Michael Keaton does full justice to Shakespeare while it adds the post-modernistic. The mannerisms are convincing, but the piece de resistance is the miming of horse riding so convincingly hilarious.

Much Ado About Nothing seamlessly bridges the gap of time between the Elizabethan and the present. It renders Shakespeare understandable, vivid, alive, entertaining and humorous. It is Shakespeare, yet a modern film done in a style that makes classical acting indistinguishable from contemporary performance. It is indeed a very dramatic and emphatic way to celebrate Shakespeare.