About two weeks ago the new vice chancellor of the University of Guyana, Dr. Ivelaw Griffith, corralled some of his associates and friends of the university at the Marriott Hotel to provide them with an insight into the state of the university, discuss the way forward, and make tangible commitments to the institution. This was undoubtedly a laudable endeavour, which apparently achieved its goal, and if the news reports are correct, commitments valued at some $14.5m were made.

Yet, important as they are, at this stage of the development of the university, such efforts can at best be only supplementary. It therefore came as no surprise that the gathering called upon the government to provide substantial emergency funding lest the university collapses. Perhaps if there was any chance that the university would have collapsed it would have been given more funds long ago but the more likely outcome of the persistent lack of proper funding would be is its perpetuation at increasing levels of decay.

Yet, important as they are, at this stage of the development of the university, such efforts can at best be only supplementary. It therefore came as no surprise that the gathering called upon the government to provide substantial emergency funding lest the university collapses. Perhaps if there was any chance that the university would have collapsed it would have been given more funds long ago but the more likely outcome of the persistent lack of proper funding would be is its perpetuation at increasing levels of decay.

As it is, Dr. Griffith is not alone in requesting more resources from the government, so he will have to present a good case as to why the university and not, say, the police, education or health sectors, etc. should be given priority. In 2012 I did a column arguing for increased government funding for the university and indicating that by regional and international standards the University of Guyana was underfunded by the regime (Gov’t can do more to fund university education. SN 15/02/2012). The situation has not changed much so most of that article is repeated below. So far as university funding is concerned, it provides a small historical backdrop, which may help us to better gauge whether the present government, in which there was so much hope, continues along the lines of its immediate predecessor.

*********

All who care to already know that funding is the major ailment affecting the University of Guyana. In 2009, I published a letter stating: “In 2003, the late Vice Chancellor of UG, Professor Dennis Irvine, (Higher Education and Economic Renewal-A Critique and Alternative Proposal) outlined what still appears to be the prevailing view. He argued that, in the final analysis, the pre-requisites for a top-class university are top-class staff and top-class facilities and that UG should make as its first priority the recruitment of quality staff, the professional development of existing staff and the rehabilitation of the physical facilities, especially the library and laboratories. According to him ‘This is something the government should be prepared to fund, and in discussion with the relevant authorities the University should make it clear that the developments which it envisages, and which it sees as making a significant contribution to socio-economic development, will only be possible if the University has the kind of solid foundation on which to build.’”

I am not coming to this issue with the misconceived notion that education is the primary driver of socio/economic development or that it is a requirement that governments ‘cannot afford not to afford’. For me, education is only one factor, be it an important one, in the process of development, but for its benefits to be maximised it must be situated in a properly crafted and implemented social policy.

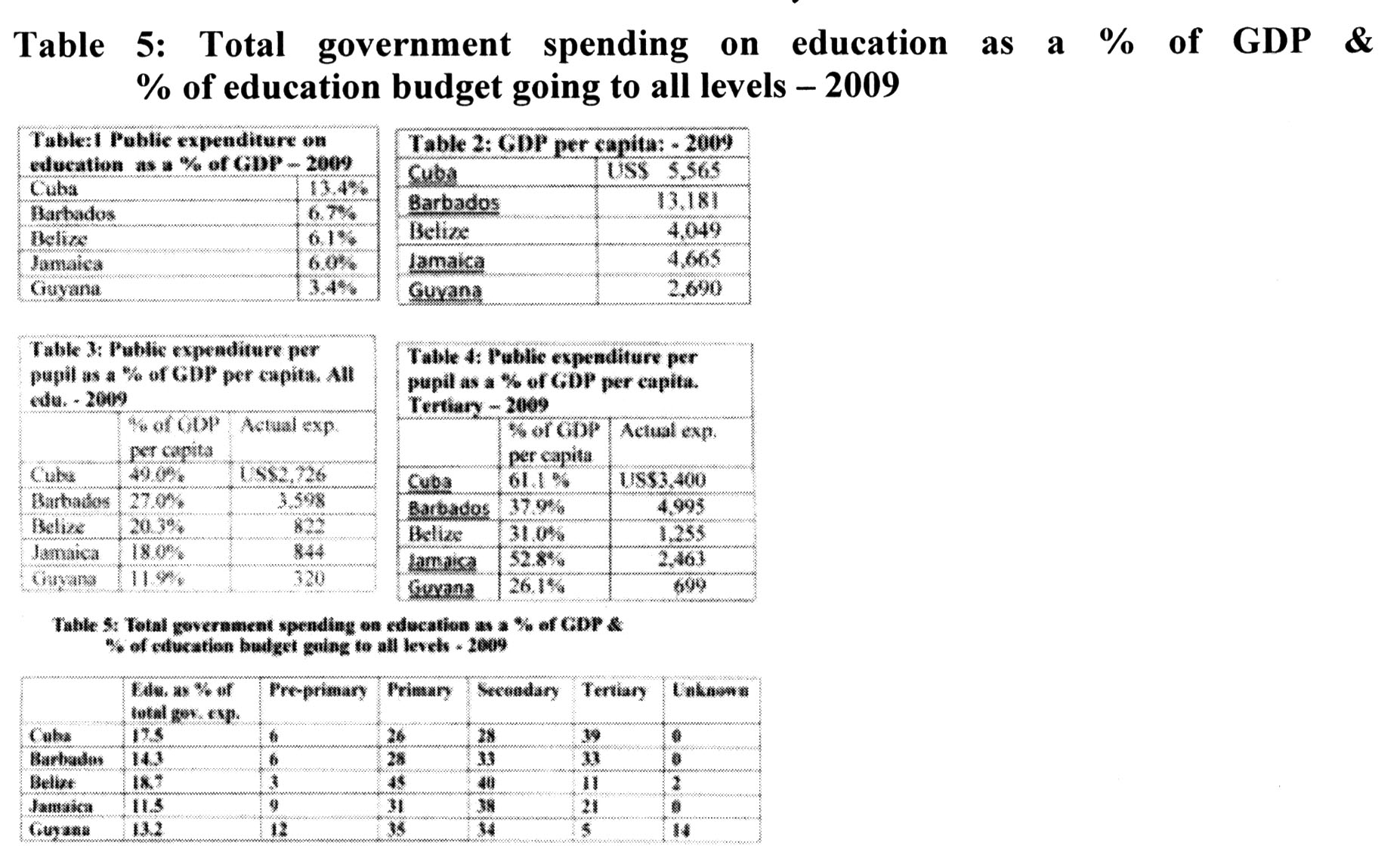

The following tables were constructed from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics online data- base and the World Bank’s World Development Indicators. The countries where chosen based on relevance and statistical availability.

Tables 1 and 2 suggest one reason why Cuba has achieved its reputation in the field of education and why we are at the lowest level in terms of educational achievement in the Commonwealth Caribbean. That country spends some 13.4% of the value of its total production on education while in 2009 Guyana is shown as spending only 3.4% (Although the figure is extremely low and maybe is related to the 2006 rebasing of the GDP). In the Caribbean Community, Barbados is thought to have arguably the best education system and the figures help to indicate why this is so. Although it spends a much smaller proportion of its GDP than Cuba, GDP per capita is much larger, allowing it to allocate an average of some US$3,598, which is more than Cuba but some ten times more than Guyana’s US$320 on each student in the education sector.

The situation is as alarming when we consider spending on tertiary education. Table 5 shows that the governments of Cuba and Barbados spend 39% and 33% of their education expenditure respectively at the tertiary level but that Guyana only spends 5%! Cuba spends 61.1% of GDP per capita income and Barbados 37.9%, allowing the latter to allocate nearly US$5,000 per tertiary pupil against Guyana’s US$700. Note is taken of the fact that tertiary education is not only university education and that allocations are usually skewed in the latter’s favour, but given the level of the comparative disparity, this can bring no solace to Guyana. Table 5 indicates that some 14% of Guyana’s education budget is not accounted for. While this needs to be noted, the proportion is so large that I believe it might well have something to do with educational allocations to our various regions.

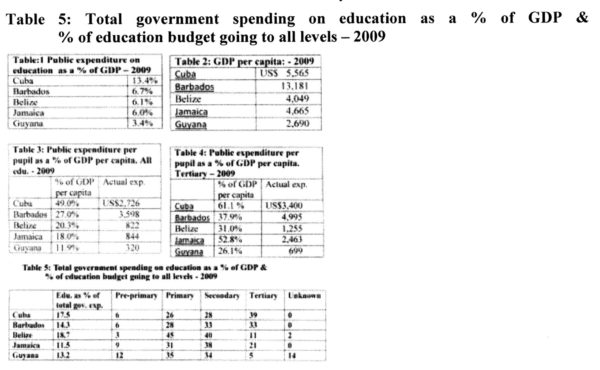

I have been told that Guyana as a comparatively poor country has no choice but to spend less on tertiary education. However, this contention is not borne out by Table 6, which suggests that irrespective of how poor you are, if you wish to have a decent tertiary education system you have to be prepared to pay for it. Burundi is the poorest in the table with a per capita income of US$163 but in order to provide tertiary education it spends over 500% of GDP per capita for an actual allocation per student of US$831. Guyana has a per capita income more than 16 times that of Burundi but spends less than that country per pupil on tertiary education.

The above figures indicate that notwithstanding its stated commitment to the education system in general and to tertiary education in particular, the regime has not been walking the talk. The government’s own numbers, found in its 2008-2014 Education Strategic Plan, show that although funding from the sector rose from US$60.3m in 2001 to US$74m in 2007, the amount going to education fell from 17.2% to 14.8% of the budget in the same period, and – according to the number in Table 6 – to 13.2% in 2009!

This suggests that the education sector has been losing its importance in the general scheme of things.

The data given above is intended to be only indicative of the kind of approach we need to adopt and some of the questions we need to answer as we go forward. The above are only some of the factors that a government must take into consideration when it seeks to establish priority and allocate funds, but my own view is that, notwithstanding our relatively poor condition, more could and should be done for the education sector. Funding university education is an expensive business but we should seek to adopt a consensual approach based upon a realistic collective vision.’