The Indian High Commission in Guyana, especially through the Indian Cultural Centre (ICC) in Georgetown, has exposed Guyanese audiences to a variety of Indian performances and cultural forms. The production last week of a programme of Bhojpuri dance and music presented by performers from India was a reminder of the importance of Bhojpuri to Guyana and the Caribbean.

The Indian High Commission in Guyana, especially through the Indian Cultural Centre (ICC) in Georgetown, has exposed Guyanese audiences to a variety of Indian performances and cultural forms. The production last week of a programme of Bhojpuri dance and music presented by performers from India was a reminder of the importance of Bhojpuri to Guyana and the Caribbean.

Last week, in highlighting the work of Tagore, mention was made of the relevance of the Bengali in Guyana. Through indentureship, Guyana imported Bhojpuri from the north of India, as opposed to culture from Bengal, in an entirely different region.

In addition to the High Commission and its ICC, there are other institutions that have been responsible for keeping Indian culture and performance alive in Guyana. These include the Guyana Hindu Dharmic Sabha with its Nritya Sangh dance company – producers of Naya Zamana; the Nadira and Indranie Shah Dance Troupe of Nrityageet fame, and the Indian Arrival Committee. These are the modern agencies, whose orientation might be a little different from that of the Indian cultural clubs in colonial times that arose out of an Indian cultural awakening in British Guiana in the first one-third of the twentieth century.

However, even with the operation of these agencies and work done by Dr Vindhya Persaud, Dr Seeta Roath and Neaz Subhan, the Bhojpuri performance was a reminder of the considerable work yet to be thoroughly done as regards indigenous East Indian cultural forms in Guyana. This is a bit ironic on two fronts – one: the producers mentioned above, specifically the dancers, have indeed presented some folk and indigenous dance on stage in Guyana, and two: the folk and the traditional have been greatly affected by attitudes in a class-conscious society since the colonial efforts of the early 1900s.

However, even with the operation of these agencies and work done by Dr Vindhya Persaud, Dr Seeta Roath and Neaz Subhan, the Bhojpuri performance was a reminder of the considerable work yet to be thoroughly done as regards indigenous East Indian cultural forms in Guyana. This is a bit ironic on two fronts – one: the producers mentioned above, specifically the dancers, have indeed presented some folk and indigenous dance on stage in Guyana, and two: the folk and the traditional have been greatly affected by attitudes in a class-conscious society since the colonial efforts of the early 1900s.

Where the second factor is concerned, some work done by three others is significant, since they have either taken a different class position, or have recognised the class issue. One of these is ‘Teacha Raghu’ (Mangal Raghunandan), a Lifetime Fellow of the Institute of Creative Arts, Guyana, who is himself a folk performer. The other two are researchers Rakesh Rampertab and Rajendra Saywack. Both Rampertab and Saywack have written on the Bhojpuri factor.

But what is Bhojpuri? It is a language. It is a cultural factor including music and dance. It is a strong movement in India, and it has had a telling impact on Caribbean culture, particularly with the rise of Chutney.

Bhojpuri is a strong linguistic and cultural force in India and the Indian diaspora, particularly the Caribbean. It is one of the seven dialects of Hindi and is actually often called Hindi in the Caribbean. And quite like the Creole activism in the Caribbean, there have been moves in India for the recognition of Bhojpuri as a language in its own right. It belongs to the Uttar Pradesh, Bihar State and other regions of northern India and was exported to Trinidad, British Guiana and to a lesser extent Jamaica during indentureship. There are also music, dance and film associated with it. There are folk dance and folk music, and in contemporary times, Bhojpuri films, popular music and videos. The cinema industry—movies in the Bhojpuri language—has grown and may be regarded as ‘Off-Bollywood,’ although some of the leading mainstream Bollywood stars have appeared in them. They have, however, been criticised for “vulgarity”. It is not difficult to understand why when considering the steamy sexuality in many of the hot and sexy songs, dances and videos by Mumbai Pictures and others. They have certainly advanced in that regard from the old stage Indian melodramas.

There are, however, brands of folk music and dance known for a range of other focuses including themes of social importance. For instance, in the Bihar region there are strong traditions of folk singing in which villagers, and travelling performers sing at weddings, or on themes surrounding rites of passage, the harvest and agriculture and other elements of social life. Religion has also been a strong influence on these songs.

Such traditions made their way to the Caribbean on the sails of indentureship. The religious remained influential throughout, but the secular folk component was to develop into very important Guyanese and Trinidadian traditions. It is believed the language of the early singing in British Guiana and Trinidad was Bhojpuri, very much continuing the kinds of themes and sentiments from the north Indian origins.

Interestingly, Saywack points out that there was also a strong tradition from Bengal in the music. While he is correct about that and provides good evidence to prove the Bengali presence, there are flaws in his main thesis. Yet the taan singing supports the strength of the roots from Bengal and other evidence shows the Madrasi background.

Clearly, then, the foundations were not laid by Bhojpuri alone, but the tradition definitely led to much of what obtains in the folk and popular music of today. The estate villagers used traditional instruments and makeshift instrumentation, and there is even a theory that African drums and drummers found their way into the music and its rhythms. But as the music developed the tassa drums and the dholak were (and are) leaders in the rhythms and percussion.

The most important musical form to develop from these roots is the chutney. Because of the dominance of Trinidadian recordings and the fact that the Trinidadian music and recording industries are far more advanced than Guyana’s, there is a belief that chutney is Trinidadian. Although Guyanese are featured in the contemporary industry, it is still thought to be originally Trinidadian. However, it must be noted that Guyana developed its own brand of chutney from the same kinds of roots and traditions as what obtained in Trinidad, but independently of it. The proof of that may be detected in the sound, tenor, language and subject matter of the old forms of chutney heard in Guyana.

Much of this emerged out of East Indian villages, estate villages and among people who were once (and some still are) estate labourers. This music is indigenous, having evolved in British Guiana from those rural settings. There is very useful evidence of this provided by Rampertab, especially his writings in the Horizons magazine, edited by Vindhya Persaud. Rampertab writes about two women who were leading performers of Guyanese chutney. Indeed the old form of this music is quite distinguishable from the soca-influenced and more hybrid forms of chutney currently popular in Trinidad and Tobago. Even the early compositions of Sundar Popo, credited with pioneering and popularising chutney as a recorded and marketed music in Trinidad, are different from those of his counterparts in Guyana in the 1970s, and their predecessors in the 1950s.

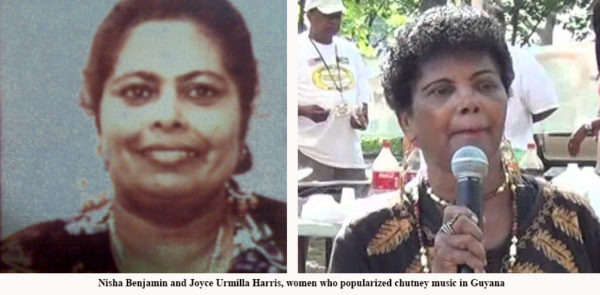

Chutney songs made popular by Nisha Benjamin and Joyce Urmilla Harris, for example, are clearly of a different strain. Such songs as “Oh Maninja” retain elements of early Guyanese chutney, even more than “Benjy Darling” which betrays some of the encroaching mix of the music. Definitely “Dis Time Nah Lang Time” is traditional stuff reminiscent of the original compositions.

Still, the best examples of this traditional indigenous chutney are in the radio advertisements that the Beharry (Bihari?) company used to advertise Indi curry powder and Champion baking powder. “. . . gyal tell me whey yu cook, nah /Indi curry an Champion baking powda.”

Chutney has certainly made great strides, particularly in Trinidad and Tobago where it has a share of the market and a place in carnival. This was propelled by a certain degree of hybridisation – the rise of chutney-soca or soca-chutney.

The brand pioneered by Sundar Popo was continued by Sonny Man – still a true brand of chutney even with the instrumentation influenced by the modern recording industry.

The explosion that followed in this music was led by Drupatee (Ramgoonai) probably the first East Indian woman to cross over into the calypso/soca arena in Trinidad. Note that her progress was already long pre-dated by women in chutney in Guyana. Drupatee’s rise was not without controversy in the Trinidadian Indian community (Saywack provides an analysis of this). Yet it is similar to the rejection and denunciation of chutney, largely by middle-class Indians in Guyana who find it vulgar and disgraceful.

But Drupatee’s “Mr Bissessar” was an explosion in the mixes, taken over by Kanshan and Babla from India and the contemporary leaders such as K I, Ricky Jai and Guyanese Rajendra Ramkellawan and Terry Gajraj. Yet, the strongest strain in this chutney-soca is still the tassa emphasised by Drupatee.