By Cynthia Barrow-Giles

Cynthia Barrow-Giles is Senior Lecturer in Political Science at the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus, Barbados.

Cynthia Barrow-Giles is Senior Lecturer in Political Science at the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus, Barbados.

“For me, a better democracy is a democracy where women do not only have the right to vote and to elect but to be elected.”

Michelle Bachelet, former head of UN Women, president of Chile 2005 and again in 2014.

BDW is the new wagon to hitch ourselves to. Earlier this month Theresa May became the second woman to ascend to the position of Prime Minister of Britain and not surprisingly one of her colleagues described her as an incredibly difficult woman. According to veteran Conservative Member of Parliament and a former Chancellor of the Exchequer of Britain, Ken Clarke, “Theresa is a bloody difficult woman, but you and I worked with Margaret Thatcher.” Equally degrading is the sale of a novelty item of United States Secretary of State Hillary Clinton as a “nutcracker”.

These are the kinds of adjectives that are normally reserved for powerful women in politics, in academia and elsewhere who hold firm convictions on issues, are outspoken, refuse to be defined by the groupthink syndrome and who also refuse to merely go along with whatever emanates from the male establishment. And if ever there was a sector of employment, that is dominated and is apparently the natural preserve of the male, it is politics.

Theresa May has acknowledged that she is an outsider, reportedly stating that, “There’s an obvious reason why I’m not part of the old-boys’ network — I’m not an old boy,” …I’ve always taken the same approach in every role I’ve played, which is I’ve got a job to do, let’s get on and deliver.” And she instantly reminds us of a Caribbean politician who many would have described as a “bloody difficult woman”. Few persons outside of Dominica knew the softer and compassionate side to her personality. That she regularly visited former Prime Minister Patrick John while in prison and his family left outside the prison walls was something she did not care to broadcast. She did what she thought was the right thing to do. That is something that many people seem not to understand.

So the expectation was that Eugenia Charles should have been more feminine, and that perhaps would have made her more acceptable. Eugenia Charles should have behaved as we are told that women ought to behave. Soft and malleable! So one of her colleagues described her thus, “Eugenia is not a cuddly person. She was highly respected but it was not the kind of old boy… First of all she is a woman…. she was not the kind of person who went out to a social evening… she would not sit at a bar…. she was not a chummy type of person. You could be very close, but not the ‘huggly’ chummy type of relationship that can develop between colleagues”. Enough said!

While I certainly cannot claim that I held any deep admiration for many of the political and foreign policy stances taken by Eugenia Charles, I did have the privilege of interviewing her and some of her colleagues a few short years before her death for an anthology, “Enjoying Power” devoted to her, edited by Professors Eudine Barriteau and Alan Cobley at the Cave Hill Campus, as part of the project, Caribbean Women: Catalyst for Change, undertaken by the Institute for Gender and Development Studies, Nita Barrow Unit.

At the time in response to a question on her relationship with her colleagues, she often said, “I didn’t have time for foolishness.” Now admittedly Eugenia Charles was then in her eighties and ailing but Charles Savarin (now President of Dominica), in describing Eugenia Charles’ approach to parliamentary business confirmed her uncompromising stance and repeated her statements, “I didn’t care who {was} doing the damn nonsense, I’m going to find fault with it. I didn’t go into parliament to waste my time, to have rubbish done. I didn’t have time to spare for that.” That is what is required in politics. Too many talkers, too little done. So bloody difficult women of whatever race, colour, nationality, age, ethnicity, and ideological persuasion, present yourself!

Clearly, not only is there tremendous diversity in the level of involvement of women in politics, but the strategies and tactics designed to influence political decisions, the degree of success they have achieved and the obstacles they confront depend on a number of cultural (including religion) geographical, economic, social and political circumstances. So we ought not to generalise, but what is obvious is that there is a tremendous gender or sex gap in politics.

Typically when we speak about women in politics we tend to view them primarily as voters and not as parliamentarians and in many countries far more women than men participate as voters and in the region as canvassers for male politicians than as candidates for political parties and only rarely as General Secretaries, Chairpersons of parties, and political leaders and fewer still as campaign organisers and party strategists.

But from 1995-2015 there has been an impressive increase in the share of women in national parliaments around the world, with the global average nearly doubling during that time – and all regions making substantial progress towards the goal of 30 per cent women in decision-making, except for the Caribbean and the Pacific. Indeed the Pacific region has been slow to change lagging behind other regions in terms of women’s share in parliament. The 2015 report of the Inter Parliamentary Union notes that the regional average increased from 6.3 per cent in 1995 to 15.7 per cent in 2015 (+9.4 points), but due primarily to gains made in Australia and New Zealand. Women’s share grew more slowly in the Pacific Islands, from 2.3 per cent in 1995 to 4.4 per cent in 2015.

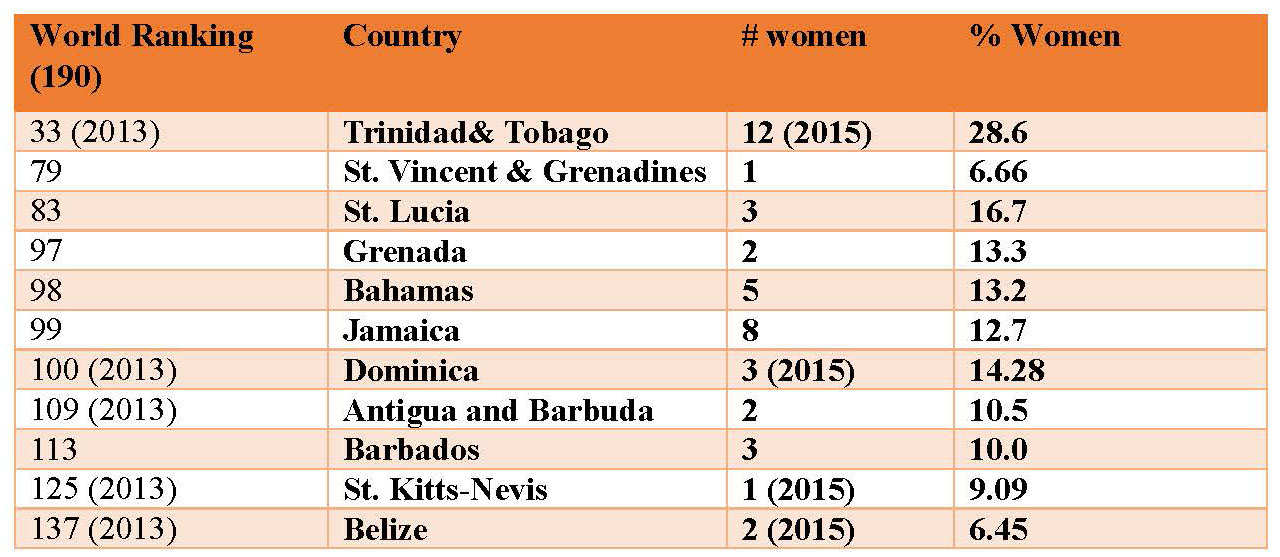

As the table below shows, the Commonwealth Caribbean still depicts a dismal picture of women in electoral politics.

Women’s Representation in National Parliaments (lower Chambers only) Selected Regional Countries

Inter parliamentary Union February 1, 2013.

Status of Commonwealth Caribbean Countries (excluding Guyana) Adjusted by Barrow-Giles (2015)

The 2015 report also points out that in 1995, nearly 61.6% of 174 countries that were surveyed had less than 10 per cent women in their single or lower houses of parliament with a mere 2.8 per cent of parliaments having attained 30 per cent or more. However by 2015, only 20 per cent of countries had less than 10 per cent women parliamentarians with 53.2% still having fewer than 20 per cent. In 8 per cent of the surveyed countries women’s representation decreased and in 2.3 per cent of these countries there was no change at all.

What are the drivers compelling such change? Undoubtedly, international and other obligations have been critical but they are insufficient as there is still much left to be achieved. Equally important to gender or sex justice is the need for women to intensify their voice and their agency by organising to demand change in not only the rules that lead to their exclusion and or maginalisation but also in the cultural, political and other mores that limit their participation. It was Karl Marx who argued that in a class divided society where class inequality is blatant, class action is imperative but can only be undertaken in a context of class consciousness. So too it can be argued that women’s level of political consciousness and empowerment be systematically enhanced as an important step towards achieving greater political equality and breaking through that highest, hardest class ceiling.

We can take a leaf from the Netherlands where the Association for Women’s Interests, Women’s Work and Equal Citizenship started a campaign called ‘Man/Woman: 50/50’ which in 1994 aimed to achieve 35 percent women in eligible places. This approach was adopted by the 51 percent coalition of Jamaica. The ten suggestions made by the Netherlands Association are:

1) Madam, you are wanted – political decision-making at the local level is important to women;

2) Women, strengthen your candidacy by training or by engaging a mentor;

3) Allies, motivate women and support them

4) Political parties, inform women about candidate selection and about the work of a councillor;

5) Local party branches, decide upon target figures on women party representatives;

6) Recruit women from other networks and organisations;

7) Break through the ‘looking for your own kind’ principle

8) Select women local party leaders heading the list of candidates;

9) Mark the names of the candidates with a M(an) or a W(oman);

10) Vote for a Woman

Women must keep their eyes on the prize and cannot expect others who do not have a vested interest in change to take that necessary step.

Three of the women referred to above have cracked the highest, hardest class ceiling, the fourth is attempting to do so and we must wait for November 2016 to see if like Margaret Thatcher and Eugenia Charles she becomes the first in the United States to have done so.