Introduction

Today’s column closes the discussion we are having on production of timber and non-timber products in Guyana’s extractive forest sector over the past decade (2006-2015). Last week’s column revealed that, similar to employment in the sector, production has been equally weak, fluctuating, and declining, as was exhibited earlier, in the sector’s macroeconomic/ national accounts performance.

It is standard to attribute this outcome of the sector’s production to two features. One is the negative impacts of weather events on output in tropical rainforests. Evidence has shown, these are notoriously negative and their avoidance requires great care is taken to plan production based on anticipated weather patterns. Unfortunately, this is rarely done by Guyana’s forest operators.

The second feature is the so-called mixed impact of the demand for wood products in both domestic and external markets. The domestic and external markets do not behave uniformly, and this is reflected in the pattern of product sales. Basically, it is found that the export market has been the main driver of production, with the shares of the local market seemingly residual. However, this circumstance is not true for all operators. As a rule, the larger ones, especially foreign-owned businesses, are more likely to fall into the category in which the external market is the main driver of production.

The second feature is the so-called mixed impact of the demand for wood products in both domestic and external markets. The domestic and external markets do not behave uniformly, and this is reflected in the pattern of product sales. Basically, it is found that the export market has been the main driver of production, with the shares of the local market seemingly residual. However, this circumstance is not true for all operators. As a rule, the larger ones, especially foreign-owned businesses, are more likely to fall into the category in which the external market is the main driver of production.

Low efficiency

As previous columns have observed, it is generally acknowledged among forest analysts that “the forest sector has been operating at a conversion efficiency of 40 per cent on average over the historic and current period” (Guyana National Log Export Policy 2016-20, Page 23). Indeed that document goes on to observe that there has been “no significant improvement in this rate over the many decades of conversion and processing.” Quite a few factors account for this outcome. And in this section, I shall indicate the more prominent of these.

First, recent surveys on the level of efficiency in the sector have found wood products conversion and processing, disproportionately utilize old machinery and equipment. Second, this circumstance places severe demands on operators to service and maintain such old machinery and equipment; in particular parts are hard to acquire (purchase). And, fabricating these locally is quite costly. Further, the revealed attitude from the survey data is that most operators wait until the equipment breaks-down, and then seek to get it fixed! Systematic scheduling of maintenance is far from standard practice for most of the surveyed wood processing concerns.

Third, in order to be in a position to provide routinized maintenance, training of the workforce becomes essential. For most operators this appears too expensive, especially when seen from the point of view of the costs of providing this training, as well as the increased payments trained workers can demand. The benefits that will be obtained from savings on break-downs, higher productivity, and better conversion efficiency rates are not as readily apparent, and are therefore overlooked.

Fourth, analysts also refer to the typically inefficient layout of Guyana’s forest operations. This feature reduces productivity in the sector, as well as the absolute output of forest products. Indeed the GFC has gone as far as claiming a number of large forest concessions “have not been making optimal use” of potential sustainable extraction. And, to the extent this is the case, they are underutilizing these concession acreages.

Substantial underutilization

A similar observation, which also reinforces the existence of substantial underutilization of production possibilities, can be made about the already installed milling capacity in the sector. Thus the GFC has reported from a recent survey of mill capacity that: 1) aggregate existing sawmill processing capacity is at 40,000m3 per month for logs (480,000 m3 of logs per year for processed logs); 2) aggregate plywood and veneer capacity is at 10,000 m3 of logs per month. This gives a Combined Milling Capacity of 50,000 m3 of logs per month or 600,000 m3 per year. Based on the information cited in last week’s column, this compares poorly with a total reported production averaging only 323,000 m3 of logs over the period 2010-2015. (Guyana National Log Export Policy, 2016-2020)

Such high levels of underutilization of both forest products potential output and processing facilities of the sector (particularly given all their defects previously identified in this column), indicate the problems of the sector are deep and structural in their dimensions. It is not surprising therefore, to discover that most of these have been echoed in a World Bank Report which had assessed ‘forestry’ as part of a larger Guyana Agricultural Sector Review Study published way back in 1992.

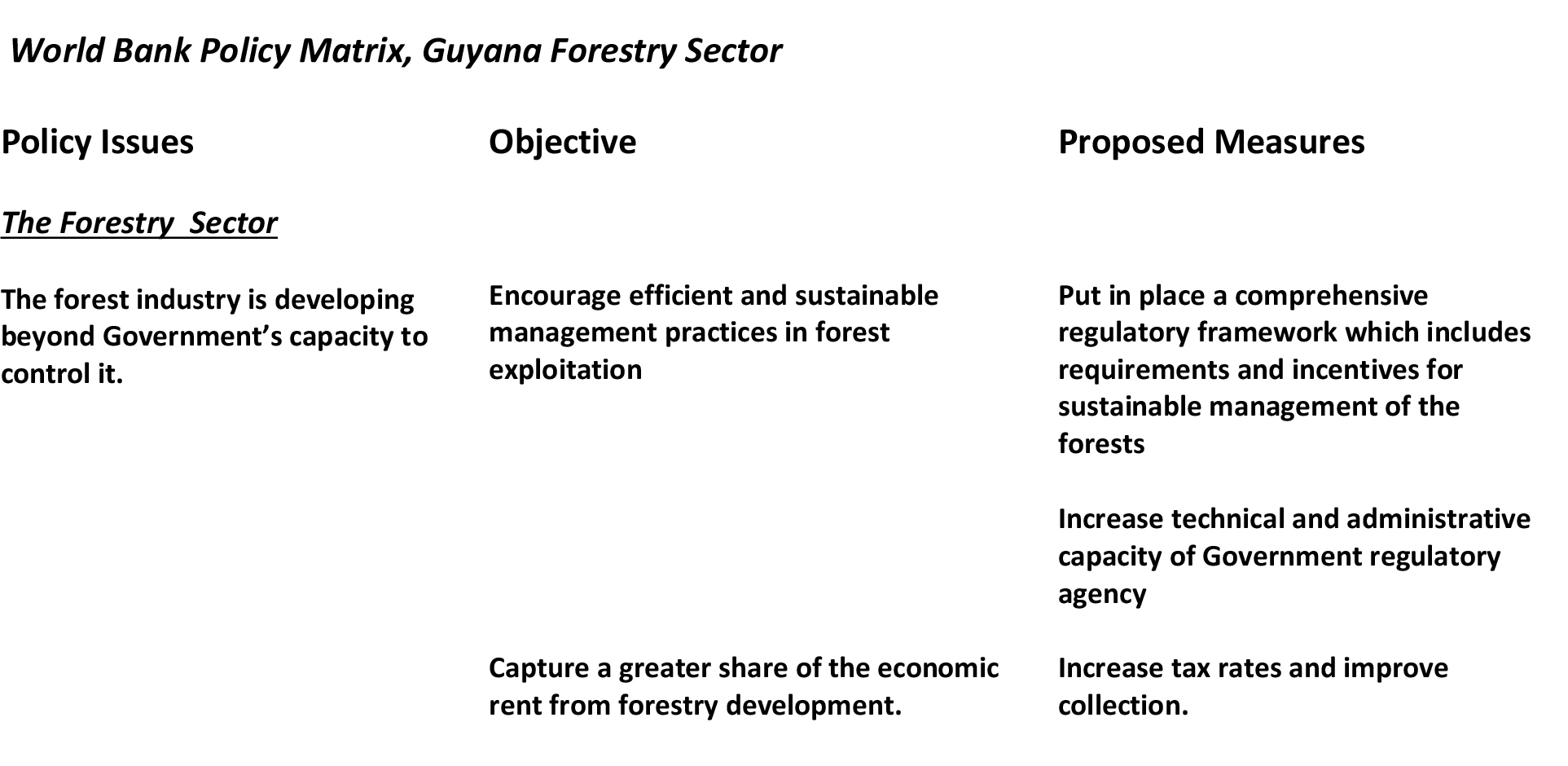

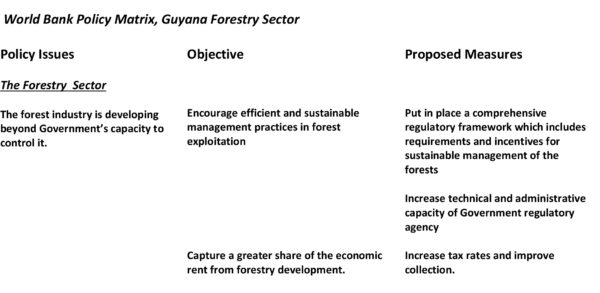

That Review had diagnosed the sector as having developed to a point “beyond Government’s capacity to control it” back then. It focused reform objectives for the sector on 1) encouraging efficient and sustainable forest management practices and 2) securing part of the sector’s value for investment in the development of the sector. For these purposes the World Bank emphasized three policy measures; namely, the creation of a regulatory framework; improvement in the technical and administrative capacity of the Government regulatory agency; and, increasing revenue flows to the agency.

That World Bank Policy Matrix for the forestry sector is reproduced below.

Source: World Bank, Agriculture Sector Review 1992.

Next week I shall examine the export performance of the sector, and then turn to discuss the GFC’s recently released National Log Export Policy 2016-2020.