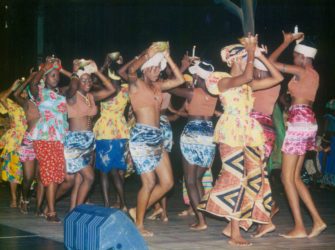

The National Dance Company (NDC) last week staged ‘A Celebration of African Heritage,’ as one of its six regular annual programmes on specified themes at different times of the year. This was a commemoration of the anniversary of Emancipation, and is no doubt very relevant to our discussion of African dance a fortnight ago.

The question of what is African dance will find further elucidation in an analysis of some of what the NDC offered in its suite of dances. The choreographies took the audience along a continuum of African dance in terms of themes, subjects and forms in modern dance, moving through items influenced by religion and traditions as well as traditional dance itself. These were approached in themes of slavery and in sections on ‘Identity,’ ‘Spirituality’ and ‘Glimpses of Traditions and Culture.’

The question of what is African dance will find further elucidation in an analysis of some of what the NDC offered in its suite of dances. The choreographies took the audience along a continuum of African dance in terms of themes, subjects and forms in modern dance, moving through items influenced by religion and traditions as well as traditional dance itself. These were approached in themes of slavery and in sections on ‘Identity,’ ‘Spirituality’ and ‘Glimpses of Traditions and Culture.’

For the most part they represented the outcome of research into African dance including surviving traditions in the Caribbean and tributes to others working in related areas of both African influenced and derived dance and music. Performances were done by the Company along with its associates, junior dancers of the NDC and students. The production included treatments of slavery such as “The Journey, “Memoirs” and others about an African identity as in “Children of Africa”. Then there was “Ode to Ailey” which adapted work based on the Black American Christian spiritual religion. There were other tributes made by way of choreography to songs about African derived traditions by Guyanese artists Dave Martins, Derry Etkins and the Yoruba Singers.

“A Celebration of African Heritage” was produced by Choreographer and Director Vivienne Daniel. She explored the African presence in Guyana and the Caribbean through such dances as “Landship”, “Bruckins Party” and “Masquerade Lives.”

What is African Dance then, where the NDC is concerned, had at least three answers. One was the use of African themes and subjects around which to devise choreographies. Two was the use of form and music like the Christian religion of Black Americans with its historical and cultural African background. Three was an exploration of Caribbean dance traditions, religious and secular, which have roots or origins in Africa and which demonstrate traditional African dance forms. In all cases these were choreographed dances rather than reproductions of a tradition.

The “Ode to Ailey” suite adapted excerpts from “Revelations” by American choreographer Alvin Ailey based on the music of Negro Spirituals. These go deep into the culture and belief of Black Americans out of the experience of slavery. It is African heritage – as the people adopted Christianity before and after Emancipation with certain styles to their music and dance with their faith and the way they express it informed by their cultural and political experience. It is dance culturally influenced by an African consciousness.

According to the programme notes, Ailey used “African-American spirituals, songs, sermons, gospel songs and holy blues” to “fervently explore the places of deepest grief and holiest joy.” Ailey described it as “sometimes sorrowful, sometimes jubilant, but always hopeful. There is the rhythm and atmosphere of black churches where the congregation would always clap their hands and dance to the gospel songs. This is not unknown in the Caribbean where the Christian “spiritual” or “revivalist” churches have that robust participatory element that quite often involves possession. In this way, there are different levels of translation of Christian worship into African styles and customs.

These very often in the Caribbean create such religions as Spiritual Baptist and sometimes just Baptist in Trinidad; the Barbadian Tie Head Religion or the Pocomania in Jamaica. Extreme forms of these will actually include real possession dances and sacrifices of fowls.

Daniel has an ongoing interest in Ailey, whose dance she has studied; various pieces from the long ballet “Revelations” form part of the NDC repertoire. In this way the company does African dance by explorations of aspects of the heritage and presence in contemporary society – in this case the expression of belief.

Many African dance traditions that have survived or have been revived in the West reflect the influence of Western society.

This is seen even among the very strongest of them such as Vodou (Haiti), Shango/Shango Baptist and Orisha (Trinidad and Tobago) and Pocomania (Jamaica). These involve the Roman Catholic Church and the Baptists. Others which are not necessarily religious or spiritual demonstrate various elements of European influence.

These were found in a dance by the NDC and associates titled “Masquerade Lives”. This was another choreography that did not try to be a direct copy of, or to reproduce the traditional masquerade as it was known in Guyana. It did not even rely entirely on traditional masquerade music. Yet the choreography treated with African dance by using the traditional form to inform the work.

There was flouncing but there was more variety than one would find in a session of flouncing.

The two most interesting pieces were “Landship” and “Bruckins Party”. The Landship is a Barbadian masquerade tradition – African derivation but with much European influence. This is a cultural movement developed among former slave communities in Barbados after Emancipation.

At its centre is the Landship dance which is a military-styled masquerade march and a maypole plaiting demonstration performed to the music of the traditional Tuk Band. The sources date its beginning as 1863, although there are suggestions that it has pre-Emancipation roots.

It imitates the British Royal Navy, with dancers dressed in naval uniform and commanded by a captain, although there may also be higher military ranks. The company of masqueraders also hold different positions and are appropriately dressed, just as in other masquerade bands of the past, or the La Rose procession of St Lucia. Apart from the highly skilled manoeuvres of plaiting the maypole, they dramatically enact other incidents such as “man overboard” when they rescue a crew member who falls overboard and revive him. This act much resembles the “doctor play” known in Jamaica’s Jonkunnu and other Caribbean masquerade performances, though none of the source accounts refer to a doctor play. This theatrical act of resurrection is found in African derived masquerade traditions.

The “Bruckins Party” is based on a Jamaican dance tradition. This is also African derived but with notable European influence. The National Library of Jamaica and other sources, like Olive Lewin, date its origin as Emancipation time – 1834 or 1838. It is known as an Emancipation celebratory dance with dancers in regal costumes to represent English Royalty at court accompanied by courtiers. However, there is a song that accompanies the dance which suggests an association with the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria in 1887. The words revolve around the refrain:

Augas maanin come again

Aagas maanin Jubilee

Queen Victoria Jubilee

Jubilee Jubilee

This is the year of Jubilee

Queen Victoria gi we free

“Aagas maanin” (August morning) is clearly the First of August and a reference to Emancipation. The mention of Queen Victoria is also linked to emancipation because the Africans had a firm belief in that monarch and gave her all the credit for ending slavery. However the song is also celebrating “Queen Victoria Jubilee” which coincided with the 50th anniversary of Emancipation; the two were celebrated together in 1888 in the Caribbean. It is not clear, therefore, whether the origin of Bruckins was 1834, 1838, 1887 or 1888.

Along with the ‘English Royalty,’ the dance involves rival courts, the Red and the Blue sets, who carry sticks and sometimes engage in a stick fight. The same rivalry is expressed in the Jonkunnu with its Set Girls in red or blue. The name “bruckins” likely comes from a particular part of the dance.

The dancers move in stately steps with one foot extended straight in front and the other knee bent. The dancers will execute a pelvic movement followed by a sudden break and spin, thus the “bruckins”. These were all suggested in the NDC choreography and are known features of African dance.

‘A Celebration of African Heritage’ by the NDC therefore demonstrates the company’s research into African dance which it interpreted in the ways analysed above. The emphasis was on modern choreographies but it appropriately sought to treat with various approaches to African dance at the time of the anniversary of Emancipation.