By Nigel Westmaas

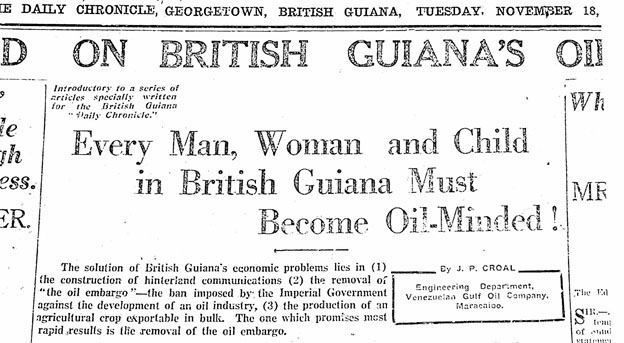

But for the name “British Guiana” the title in the image above could have been written in 2016. Yet, this eerily contemporary statement actually came from a Daily Chronicle editorial published on November 18, 1930, some 86 years ago. The editorial called on British Guianese to be “oil minded” as “the first stepping stone to progress along the lines of oil development…” adding that “there is a fair prospect of the colony developing a lucrative oil industry…”

It urged “every man, woman and child” to “think oil, dream oil, and co-operate in virile campaigns with the object of inducing our masters at Downing Street to lift the pernicious ban.” The ban or restriction in question was a likely reference to the British (Mineral Oil) Regulations of 1912. This restriction was aimed at foreign companies and citizens other than “British subjects” and applied to the “transfer of mineral-oil rights and property to aliens.” No one can say for sure what prevented the exploration and development of oil in British Guiana at that time. Perhaps British geo-political caution was one factor. Then the First World War stepped in and new directions and geopolitical distractions turned Britain and other potential prospectors away from British Guiana to the Middle East. It appears from press reports that by 1930 Britain relaxed the restriction on the search for petroleum in the colony by foreigners.

A Guyanese engineer, JP Croal, who worked for Gulf Oil in Venezuela, was quoted by the Daily Chronicle as exhorting the colony to drill for oil in British Guiana. Croal complained about British Guiana’s lost opportunities and invited “public men, political agitators and political parasites, doctors, lawyers, merchants, managers, clerks, schoolmasters (who are particularly tasked to drive the idea in the heads of the pupils), washerwomen, fishmongers, and all and sundry…” to ask him questions about oil’s potential in the colony. Meanwhile Venezuela, at the time Croal was writing, was already producing oil under its dictator Juan Vicente Gomez. In fact, Venezuela had moved from producing 1.4 million barrels of oil in 1921 to 13.7 million barrels by 1929, a gigantic production leap echoed by Saudi Arabia in 1930 where British negotiators persuaded the then King Saud to open up oil concessions. At first the cautious King Saud was reportedly only intent on pursuing water wells but was eventually convinced about the efficacy and impact of oil on the Kingdom. The rest is history.

A Guyanese engineer, JP Croal, who worked for Gulf Oil in Venezuela, was quoted by the Daily Chronicle as exhorting the colony to drill for oil in British Guiana. Croal complained about British Guiana’s lost opportunities and invited “public men, political agitators and political parasites, doctors, lawyers, merchants, managers, clerks, schoolmasters (who are particularly tasked to drive the idea in the heads of the pupils), washerwomen, fishmongers, and all and sundry…” to ask him questions about oil’s potential in the colony. Meanwhile Venezuela, at the time Croal was writing, was already producing oil under its dictator Juan Vicente Gomez. In fact, Venezuela had moved from producing 1.4 million barrels of oil in 1921 to 13.7 million barrels by 1929, a gigantic production leap echoed by Saudi Arabia in 1930 where British negotiators persuaded the then King Saud to open up oil concessions. At first the cautious King Saud was reportedly only intent on pursuing water wells but was eventually convinced about the efficacy and impact of oil on the Kingdom. The rest is history.

The question can be asked, based on our present-day knowledge of tenuous Guyana/Venezuela border relations, why a Guyanese working in the oilfields of Venezuela would be calling for a search for oil in British Guiana at that time. The reason is simple. The Venezuela-Guyana border controversy was not yet re-opened. The boundary between the two countries was considered a ”full, perfect and final settlement” by an international Court of Arbitration in 1899 but became an issue of contention about 1949, following the publication of a posthumous memorandum (written in 1944) of dissent with the original settlement by an American lawyer Severo Mallett-Prevost. Mallet-Prevost was the lawyer representing the interest of Venezuela during the 1899 arbitration.

The debate in the British Guiana press in 1930 presaged some of the contemporary discussions on the advantages of oil discovery for Guyana.

In 1919 the Colonial Office (British) granted to Elliot Alves, the chairman of the Venezuelan Oil concession, the rights to found an oil industry in Guyana. Michael Swan, in British Guiana: The Land of Six Peoples, referenced the early conjecture in Guyana that oil might be found in the North West district. In 1940-41 a company called Trinidad Leaseholds Ltd made a survey for oil in the area between Demerara and Corentyne but with no success. Swan concluded that it was “unlikely that oil will be found in the colony because the greater portion of British Guiana is composed of rock which was formed by extremely high temperatures so that any original organic materials held in these rocks would have been destroyed.”

But the search did not end there. In the 1950s there was a flurry of requests to search for and drill for oil, mostly in coastal Guyana.

The British White Paper of 1953 suggested that Gulf Oil Corporation “withdrew their application for an exploration licence” while Panhandle Oil Canada

Limited had abandoned “further exploration pending the clarification of the political situation.” The political situation of course was a reference to the election of the PPP government in the same year and the resulting political upheaval over the suspension of the Constitution by the British government.

The McBride Oil & Gas (Texas Company) sought and received a concession to explore for oil along the coast and offshore in 1954.

In 1958 Standard Oil signed an agreement with Governor Sir Patrick Renison to permit offshore and coastal exploration of the colony.

Soviet special representatives came to British Guiana in 1962 amidst political turmoil and a raging global Cold War and reportedly found a “promising oil bearing area of about 40,000 square kilometres” of the country that was likely productive.

But all the foregoing efforts to locate oil were either unsuccessful or stalled.

In 1972 Guyana closed down the Georgetown to Rosignol railway because oil was plentiful and cheap globally. Approximately a year later came the 1973 oil embargo and the cost of oil shot upward causing a global crisis; now the decision to terminate the railway appeared imprudent. Subsequent woes in Guyana and other countries proved the correctness of actively distrusting even stable commodities such as oil on the world market.

The search for oil, or the concern that oil was needed apparently returned, as in 1981 the then PNC government announced plans to establish a national petroleum corporation to supervise oil exploration and development. The minister in charge Hubert Jack told the Guyana National Assembly that “prospects for finding oil in commercial quantities were good.” But Guyana’s economy at the time would have been relatively free of the obsession with the search for oil as there were other “commanding heights of the economy” available. For centuries, beginning from the period of slavery, sugar stood out as the standard bearer for the Guyanese economy. Bauxite came later.

Alan Adamson, in Sugar without Slaves, reflects on the rise of British Guiana’s (Demerara’s) export of staple products between 1789 and 1802. According to him, sugar exports rose by 433 per cent, coffee by 233 per cent and cotton by a whopping 862 per cent in that period. It was deemed the “planter’s golden age”. After cotton and coffee had withered away sugar became number one, lasting seemingly for an eternity with the moniker “Bookers Guiana” in tow. Bauxite became a significant boon to Guyana’s economy for a while but this too waned by the 1980s. Sugar has declined from its central role in the Guyanese economy over the last few decades and has for all intents and purposes collapsed. Oil has now become the new refrain of economic rescue, success and glory.

The dream realised?

One of the first acts of the new APNU+AFC administration in May 2015 was the invitation to President David Granger, Minister of State Joseph Harmon, and AFC Executive Member Raphael Trotman (Trotman was not yet Minister of Natural Resources) to be flown to see the Exxon Mobil rig and its active work on the newly discovered area for exploration, 100 plus miles off the Guyana coast. The image of the Guyanese leaders on the deck of the oil rig was symbolic of new energy and a potentially new lease on life for the Cooperative Republic with the prospect of dazzling oil revenues. The expectations were initially placed in the context of immediacy. But with subsequent releases from Exxon Mobil and the government of Guyana some aspects of the enthusiasm were backpedaled. The reality of oil companies and their technical and economic power and leverage over small states looms over any negotiation and agreement. For its part the Guyana government subsequently announced its own priorities. The timing for the benefits accrued from oil drilling was pushed back to 2021. Reality, it appeared, had set in.

Exxon-Mobil—a tributary company of the first and once powerful global oil giant, Standard Oil—is now the de facto multinational that can facilitate incredible wealth which can either turn country’s fortunes around, or lead to ruin when the host society is unable to manage its petroleum revenues.

The ABC countries have already stated that Guyana will be “in complete control of its destiny” and that the Guyana government will be negotiating with a private company, in this case the conglomerate Exxon-Mobil. Of course, statements are one thing, reality is another. The history of the major Western capitalist economies is that they have multiple options and hidden and open ways to place pressure on governments in the developing world. Guyana for its part announced a new regulatory mechanism in the form of an oversight body to monitor the expected 700 to 1.4 billion barrels of oil at the Liza sites. The thirst for black gold is now as much in the air as it was back in 1930 when a Daily Chronicle editorial enthused:

“Black gold has made the wealth of America, it is creating wealth for the neighbouring republic of Venezuela, it has enabled Trinidad to withstand the shocks of sugar and cocoa adversity, and if the results of recent prospections in British Guiana are fulfilled it should provide more real prosperity for this poor benighted country than was ever dreamed of…”

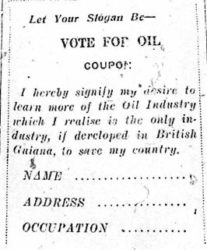

Whatever the result of the Exxon-Mobil oil exploration for Guyana it is absolutely necessary that Guyanese from all walks of life and positions in and out of the state weigh carefully one point in the Vote for Oil coupon from the Chronicle of 1930: “learn more about the oil industry” before oil flows and money is transferred in 2021.

Is Guyana prepared for oil after a relatively long search?

Whatever the outcome for petroleum revenues in the next few years, Guyana cannot be complacent in ongoing negotiations with Exxon-Mobil and with the use of oil wealth in the society at large. As noted in other historical experiences, even very wealthy oil societies like Trinidad, Nigeria and Venezuela have succumbed to the vagaries of the international market as well as to corruption, mismanagement and misuse of oil revenues. Can oil provide the epic needs and changes that Guyana requires? Or will it, as in the case of our neighbours Venezuela and Trinidad, provide mixed or even fatal results? Will the expected oil wealth be equitably utilized or squandered in the hands of a corrupt few or mismanaged by another modern state that possesses no clue how to be transparent and fair with economic riches? What are the potential environmental hazards of oil mining? Restating what the Chronicle printed in 1930, we must become “oil minded” in both senses, that of expectation and that of caution in relation to the advent of a new lease on economic life for Guyana in the form of oil money.