Castellani House is currently exhibiting “Homage to Denis Williams: An Exhibition of Artworks by Indigenous Artists – Celebrating Amerindian Heritage Month” at the National Gallery of Art, running until October 15.

This is another very significant display of work that illustrates the impact and importance of Amerindian art or the Amerindian presence in Guyanese art. These have become much more notable and thematically specific since the 1990s when the Indigenous factor emphatically claimed its place in the art of the nation.

This is another very significant display of work that illustrates the impact and importance of Amerindian art or the Amerindian presence in Guyanese art. These have become much more notable and thematically specific since the 1990s when the Indigenous factor emphatically claimed its place in the art of the nation.

In the colonial era, pre-independence Guyanese art developed after a long period when expatriate and visiting artists drew and painted impressions of Amerindian life through the nineteenth to the twentieth centuries. These included nineteenth century paintings by WH Hedges and Edward Goodall in particular, who simply represented people and landscape which documented visits to the interior. The work of Hedges was brought to general notice by Prof Sister Noel Menezes, while Goodall produced much work in support of anthropological explorations, particularly when he was hired by Robert Schomburgk. Others doing similar work were WL Walton and Dr William Leary Echlin.

For a very long time, extending beyond independence, that was the general representation of the native Amerindians in Guyanese art. There was a major change in the 1980s led by the work of Marjorie Broodhagen, Stephanie Correia and George Simon. Broodhagen, a major Guyanese artist, showed work with the influence of the Indigenous heritage both on canvas and in tapestry. A famous sample of this work used to be hanging in the George Walcott Lecture Theatre at the University of Guyana. Correia produced a large volume of ceramics making rich use of motifs and images, until she began to do the same with small drawings and paintings. Simon gradually developed as a painter with large canvases depicting hunters and other aspects of life.

The first important national impact that made a breakthrough and imposed the true depth of Amerindian art work was in 1989 when Oswald Hussein won the Guyana Visual Arts Competition and Exhibition with an outstanding work of sculpture that introduced the profound spirituality of the new Amerindian art that was developing. This piece of work heralded the shape of what was to come.

But it was not until the late 1990s that Amerindian art clamorously announced its arrival with the exhibition by “Six Lokono Artists” at the Venezuelan Cultural Centre in Georgetown. These artists were led by Simon who tutored most of them in St Cuthbert’s Mission and included Hussein (Simon’s half-brother), Linus Klenkian, Telford Taylor, and Roaland Taylor.

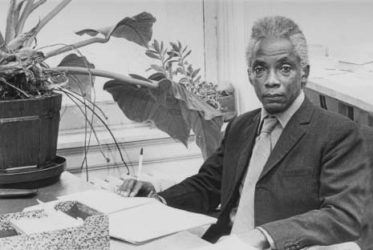

This exhibition pays homage to Dr Denis Williams, foremost Guyanese and Caribbean archaeologist and anthropologist, founder of the Walter Roth Museum and a major artist. Williams started off many other important movements, including the founding of the Burrowes School of Art and it was his painting, Human World, that was repatriated from England to establish the National Collection now housed in the National Gallery of Art in Castellani House. The exhibition is in his honour as an artist and as the great authority on Guyanese pre-history and the documentation of the ancient Amerindian presence in Guyana dating back 7,000 years.

Ohene Koama describes Williams as “a distinguished artist and writer” who further “founded the Museum of African Heritage (1985) and the National Gallery of Art, Castellani House (1993).” Koama explains that the exhibition, “led by the artist and archaeologist George Simon, an understudy of Dr Denis Williams, continues a trend where the sacred and secular art forms of the Indigenous peoples, bound in a variety of media, are summoned for expression and interpretation.” The creations flourish “where motif, form and subject matter compete and jostle for dominance.” (Exhibition Catalogue)

Williams’ relevant connection to the Amerindian heritage is also underlined because of the extensive work he did among the Indigenous people, and Jennifer Wishart, another understudy of his and former director of the Walter Roth Museum (and researcher at the UG), gives an insight into the ethos of how the people relate to the work. She recalled “stories of kanaima and the piaiman” and learning “to look at the leaves on the trees if I wanted to know if it would rain soon.”

It is those Indigenous spiritual elements that lend depth and meaning to the art and help to give it its distinct identity. The power of that element is not as terrifying as in the Lokono Artists’ show of 1996, since at that time it was new and more concentrated in a smaller exhibition, but there are pieces here now that recall that quality – Edward Klenkien’s “Anaki”, for instance, and Roaland Taylor’s “The Power of the Forest”.

There is notable new work from Victor Captain, who would be fairly new to the public audience, particularly in his large pieces “Shape Shifter” and “Protector”. The case of Nigel Butler is similar with his suite of “United #1, #2 and #3”. Anil Roberts, a promising painter represented here by “Mother Nature” and “The Chant”, will be remembered as a former student of Simon at UG. More widely known would be Anna Correia-Bevaun and her striking employment of motifs in “Pottery and Carpets” and “Curtains and Pots”. Desmond Alli is even better known as a sculptor, but in this exhibition shows off his more recent preoccupation with acrylic on canvas and mixed media. Indeed, his “Cosmology of Pre-Columbian Civilizations” is the most impressive of his paintings, a very large canvas with his most successful attempt at exploring motifs, imagery and colour.

But that spiritual factor is most startlingly evident in some of the pieces from Simon and Hussein whose work fairly well dominate the exhibition. Where the larger pieces of sculpture are concerned, Hussein’s “Tribute to the Ocean” is memorable for its carved and polished precision which only pretend to conceal the suggestion of the uncontrolled supernatural. Equally so is another of the larger exhibits in saman, which are of similar interests in bird beaks, bird spirits and spirits of the forest that made Hussein so exceptional when he rocketed to fame in 1989.

“Sakanto” is less imposing in size but just as outstanding in its quality of mystery and of protean forms among the forest animals and landscape. Many other pieces continue that preoccupation, recalling such presences as kanaima, hunters and ventriloquists in animal or forest form, as Hussein tell tales without the use of any human figures. These may be found in a variety of pieces such as “Dog on Moon”, “Anaconda”, “Mask” and “Jaguar” – a popular manifestation of the shape-shifting kanaima.

At this phase of his long career, Simon does not fail to surprise with a fresh approach to his studies of the environment, animism manifested in protean animal forms not unlike the interests of Hussein, and the rainforests. He shows off a new suite of very large canvases such as “Aishalton”, “Tree Dimension #1” and “Forest Lotus”. These works in oil and acrylic are dominated by a motif of roots in keeping with a prevailing imagery of forest trees, gnarled roots, branches and contact with the earth.

“Aishalton” recalls the Southern Guyanese village, famous home of petroglyphs and rock paintings. Here Simon interplays these Amerindian motifs with those of the roots to capture audience interest in yet another new collection of paintings. It is a master class by a foremost painter. He does a similar mix of images and motifs in “Bimbiri – Dragon Fly”, where roots translate themselves into forms suggesting the dragon flies.

All these works are connected by the techniques and prevailing visual impression. “Umana Yana – Meeting Place” is an abstract piece based on the Indigenous ‘benab’ such as the one reproduced in Kingston, Georgetown, as well as the concept of a place for ceremonial meetings. The roots continue to be ubiquitous vehicles for inexhaustible and infinite shapes and suggestions, spectacularly presented in a range of colour schemes. In these paintings the use of colour help to demonstrate yet again a fresh, new Simon; this time with bright, rich colour blends and shades which are yet lighter in tones and certainly not near to primary colours. They are reminiscent of the way Simon shook up his audience with a new flair in his series of the “Shaman” and “The Milky Way”, and again with his explorations of kanaima-like jaguars, spots and mergers of myths and painted forms.

Like the “Homage to Wilson Harris” painted by Simon, Roberts and Philbert Gajadhar on the UG Turkeyen Campus, this tribute to Williams honours another Guyanese artist, a writer whose archaeological work ties him to the Amerindian heritage in Guyana. It is an imaginative way for Castellani House and for the several Amerindian painters and sculptors to give a visual offering to a master in celebration of the month of Amerindian heritage in Guyana.