I didn’t set out to write books. I wanted to read and publish. But at some point I was inspired when I read Toni Morrison saying ‘if there is a book you want to read but it has not been written yet, you must be the one to write it.’ After I’d made up my mind to self-publish, swallowing the sensation of ego tripping and self-aggrandisement, there were some possibilities to be published by others. But I’d made up my mind that I could do both – write the books and publish them especially because publishers weren’t interested in publishing them.

Again, Toni Morrison, my mentor elect says that though the writing will be difficult, this should not be visible in the finished product. Those difficulties and product must appear symbiotic. Becoming philosophical is a great way to surpass those obstacles that greet you daily as you pursue any kind of vision. You have to tell yourself you can do it. And believe it. It must in fact be your will to prove it to yourself that such is possible. Doubt, anxiety, fear, lack of finance must be countered by constant affirmations like ‘only good can come.’ It became important for me also to speak less about the difficulties – which is half the task of overcoming and more about the learning experiences that come with the challenges. I learnt to appreciate ideas about the Universe responding to positivity and wanting us to succeed. It delights in success; sets up opportunities that mask themselves as challenges merely to test our Will.

So why these books?

An abridged answer is that I saw the pursuit of writing and publishing these particular books as a necessary homage to my ancestors. There is a vacuum of publications from a Guyanese perspective that look at traditional African practices and their retentions in Guyana. This is the case for both fiction and non-fiction.

Guyanese Komfa: the ritual art of trance – is from my PhD research, which was completed in 2009. After I finished, I tried to send the thesis to publishers but responses didn’t come, though this would have been my preferred route. I made initial attempts to contact publishers, but didn’t always pursue them after I didn’t get a response which may be because I sensed there might be issues with the form of the work.

Guyanese Komfa: the ritual art of trance – is from my PhD research, which was completed in 2009. After I finished, I tried to send the thesis to publishers but responses didn’t come, though this would have been my preferred route. I made initial attempts to contact publishers, but didn’t always pursue them after I didn’t get a response which may be because I sensed there might be issues with the form of the work.

It is multi-disciplinary, combining critical theory, social science, literary criticism and creative writing. I believe it was partly this that meant I was not rewarded funding by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) when I appealed for their assistance to do the PhD. The research proposal was turned down by Goldsmiths University which wanted me to do something on literature only – keeping it as a one discipline thing. I didn’t think that would have worked in the same way. I was eventually awarded a scholarship by my University, through the Caribbean Studies Centre at London Metropolitan University, headed by Professors Jean Stubbs and Clem Seecharan (a fellow Guyanese who was very supportive). Komfa, which acknowledges spirits of all the ethnic groups in Guyana is a powerful symbol of cultural identity for me. I used Dr Kean Gibson’s book Comfa Religion and Creole Language in a Caribbean Community (2001) as a main source, but this work was primarily sociological, though linguistics was also featured. I wanted to show that Komfa, as well as its social emphases can also be used to critically analyse the post-colonial and racially divisive political context of Guyana. It was for this reason that I chose to include a novella – titled ‘Komfa’ at the back of the book; but which has been independently published as Something Buried in the Yard. What is presented in Guyanese Komfa: the ritual art of trance is essentially a complex perspective that Guyanese seem at once to know and not know. Certainly there needs to be more understanding about it. Elder Eusi Kwayana was very encouraging of the original ideas for the work and it was he who introduced me to Kean Gibson’s book on Komfa. In his Preface to Guyanese Komfa he writes:

“Scholars may identify Komfa people by ethnic or regional origin. I knew one scholar who was a Komfa person from a Komfa mother who converted to Catholicism and suffered headaches. My own identification of the true Komfa people – and it is not anything I can ask a reader to accept – is by the Dance. I have seen in Guyana and Suriname this dance in which the feet of the votaries seem not to touch the floor or the ground of the Ganda. Asantewa captures this faculty in her fiction, but it is no fiction. I had told myself, subject to better and more certain knowledge that this feature is the reason that the Dance is called ‘wind dance’ in Guyana… As a person not up to date with the academy I found it new and refreshing that a novella about Komfa people was allowed in a thesis, not the topic, but the form of the work…Asantewa is aware that the story of Komfa is again coming into its own as a popular mode of communication. There is at least a strong current of popular preference for the story among forms of knowledge delivery. Her fiction captures the complexity of attitudes within any group coexisting with its unity. This condition is true for Komfa people as it is for Guyanese society and the nation building project overall.”

Something Buried in the Yard is extracted from the larger theoretical work in Guyanese Komfa. For expedience, here’s the synopsis:

“Something Buried in the Yard journeys into the Guyanese subconscious imagination, where identities are configured not by politics and race but cultural and collective experiences. The spiritual practice of Komfa is performed as a sacred ancestral rite and healing of the nation. The novel is set in 1992, at the time of the election that ended the 28 year rule of the African led People’s National Congress, and which gained victory for the East Indian led People’s Progressive Party. Explored through the eyes of ancestral spirits, this powerfully intriguing narrative compels all its characters to re-examine personal histories and ways of interacting with each other and their world.”

The title is a metaphor for the forgotten African ancestral traditions. It highlights the significance of reconnecting with traditional practices through which Africans felt at one time socially empowered. I hoped it might encourage Guyanese particularly to reimagine their sense of cultural and national identity, given its inclusion of the other ethnic characters comprised in the narrative. For others in the African diaspora, it is hoped that the book would reshape sensibilities about spiritual phenomena and address the cognitive dissonance that blights our understanding. In other words we know about these practices but generally pretend we don’t – as signalled in repeated phrase ‘see and blind. Hear and deaf’. The self-denial, consequent of enslavement and colonisation needs to be redressed. We’re actively continuing our psychic persecution by refusing to face what we know to be real. Komfa exists; it involves trance, spirit possession or altered states of consciousness, whichever way we choose to describe it. When knocked, the drums will rouse spirits – and some will respond and dance. Others will never return to that space mostly out of fear. Something Buried asks Guyanese to face the fear and the ambivalence about our traditional practices through which means we might begin to appreciate our dynamic cultural affinities.

Mama Lou Tales is a biography of my mother. I can’t say why I chose to publish this book alongside the two above but it complements my focus on folk narratives. It honours and acknowledges the life of a very ordinary woman, who like many made the journey outside Guyana in search of betterment. I had always questioned her life choices – which naturally impacted our lives. Why, for example, she left my father to rejoin the man who abandoned her, though he was her husband. She rarely complained about our ‘lot’ – that we don’t have material stuff; ‘silver and gold I have none’ she’d say, ‘but I have the word of God,’ embodied in the Bible (in her estimation a wonderful gift for which we should be grateful). We differed in our interpretations of God, but we are finally at some middle ground, I believe. I accept that not every ‘why’ has a ‘because.’ As well as telling my mother’s story, the book retells some familiar stories of village life in Guyana. For example, this one I titled ‘Baiya been hungry:’

“Three small boys love making mischief. Deh live near dis Indian lady in duh village. And yoh know dem houses deh close close under one another so yoh could see wha’ people doing, when deh cooking food and soh. Duh lady husband die. So she does be cooking and carrying food to feed he at duh burial ground. Dem lil boys following she all duh time fa see where she going wid duh nice food she cook. One day deh run ahead of she, climb up a tree and watch she put duh food down fa she husband. When she gone, dem boys come down from duh tree and eat out duh lady dead husband food and wrap deh plate an’ soh in duh towel.

Next day, she goh back fa put more food. She see duh containers empty. ‘Ow,’ she say, ‘Baiya been a hungry. He eat out all duh food.’ Dis time dem lil boys up in duh tree, hearing she and killing demselves wid laugh.”

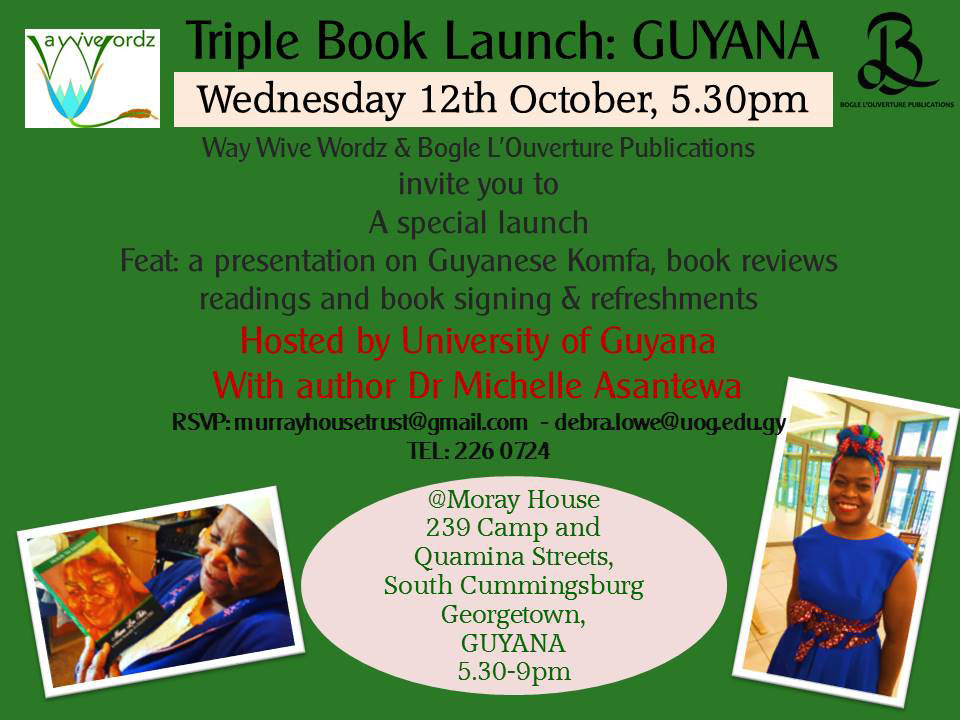

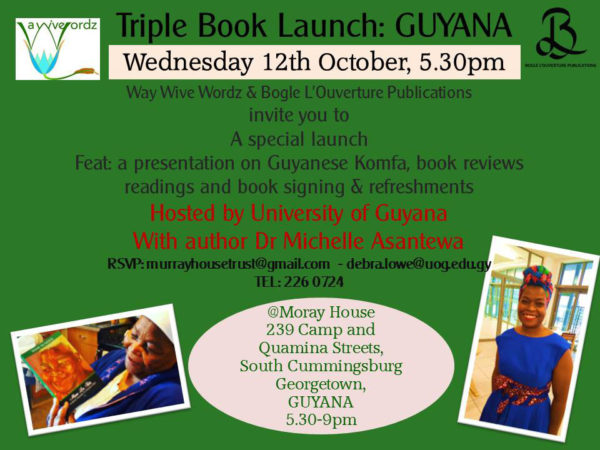

I’m especially looking forward to seeing the responses to the books in Guyana. A launch, hosted by the University of Guyana will take place at Moray House on 12th October at 5:30 p.m.. In writing and publishing these books I feel I’ve proven myself to myself. So finally I hope they will contribute to the continuing celebrations of Guyana’s 50th and a welcome tribute to Guyanese folk.