In today’s column I introduce the second topic in the series appraising Guyana’s economy in the coming time of oil and gas production and export. This topic will be presented in two parts. First, I provide a brief delineation of the oil and gas discovery, based on company releases and reportage in industry publications. Second, I summarily appraise the complex issues to be encountered when transforming the “discovery” into production and export.

In today’s column I introduce the second topic in the series appraising Guyana’s economy in the coming time of oil and gas production and export. This topic will be presented in two parts. First, I provide a brief delineation of the oil and gas discovery, based on company releases and reportage in industry publications. Second, I summarily appraise the complex issues to be encountered when transforming the “discovery” into production and export.

Before starting this task, I must respond to those readers asking me to provide an ndication of estimated global medium and long-term oil demand, derived from the same sources utilized when drawing policy lessons for Guyana. This information should help provide a more rounded picture of the four policy lessons, discussed in the two previous columns. This information is provided in the next section.

World oil demand

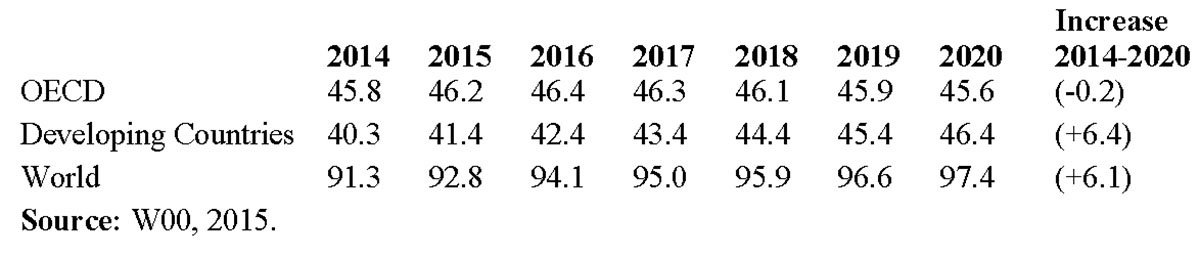

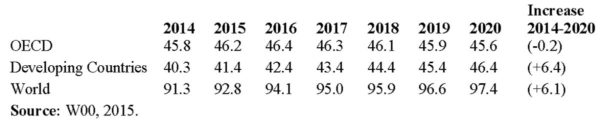

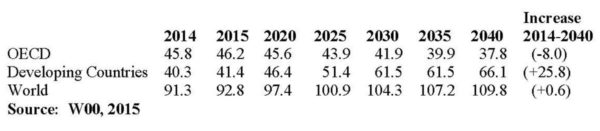

Tables 1 and 2 respectively, indicate estimated global oil demand over the medium (to 2020), and long-term (to 2040), as revealed in the World Oil Outlook, (WOO), 2015. It shows that over the medium and long-term, the developed (OECD) countries will face falling demand. Indeed, as this decline steepens, the further the estimates go out in time.

However, the reverse occurs for the developing countries. Their oil demand accelerates going forward in time; increasing by 6 per cent over the medium term (2020), and rising to 26 per cent over the long-term (2040).

Table 1: Estimated Medium-Term Oil Demand (MB/d)

Table 2: Estimated Long Term Oil Demand

For the world, the estimates reveal an increase of 6 per cent over the medium term, falling to a marginal increase (0.6 per cent) over the long-term. In the previous columns on this topic, I have already indicated the complex considerations which drive these outcomes. I will not repeat here, but portray in the next section the so-called “potentially massive Guyana discovery”.

‘Potentially massive’

Regrettably, there was not much information I could access in the form of articles, essays, or other extended literature detailing Guyana’s oil and gas exploration prior to Independence. Wikipedia reports oil exploration gained significance in the 1940s. It was later though, in the 2000s, that this exploration became noticed worldwide and the oil majors began to show increased interest. Indeed, the US Geological Survey’s World Petroleum Assessment, 2000, had identified the Guyana-Suriname Basin as a significant reservoir, potentially holding as much as 15.2 billion barrels of oil, which would make it one of the world’s largest identified deposits.

Last week’s (September 25) Sunday Stabroek carried an enlightening piece by Nigel Westmaas, referring to aspects of the pre-Independence “search for oil in Guyana”. As he has indicated, American majors as well as the Soviet Union had showed interest in oil exploration during the 1950s. Further, the public had demanded pursuit of oil exploration as Independence approached.

As matters presently stand, industry specialists allude to what is known geologically as the ‘Atlantic mirror image theory’. This theory posits that the offshore ‘Upper Cretaceous Formations’ in our basin mirror that of West Africa on the other side of the Atlantic, where billions of barrels of oil have been ‘discovered’, including Ghana’s recent offshore Jubilee deposits.

Stabroek Block

Guyana’s discovery is located in the Stabroek Block. This is an area of 6.6 million acres or 26,800 square kilometers offshore the Guyana coastline. Oil and gas exploration is taking place there under an agreement between the Government of Guyana and ExxonMobil’s local subsidiary, Esso Exploration and Production Guyana (45 per cent ownership), along with its partners: Hess Guyana Exploration (30 per cent) and China National Offshore Oil Corporation, CNOOC Nexen Petroleum Guyana (25 per cent).

During the late 2000s, four companies were engaged in oil and gas exploration in Guyana; ExxonMobil, Repsol, Century Guyana Ltd, and CGX Energy.

The ExxonMobil discovery was announced in May 2015, after the successful drilling of its Liza-1 well. This well was drilled to 17,825 feet in 5,719 feet of water, located 120 miles off the coast. It encountered 295 feet of oil bearing sandstone reservoirs. The initial estimation was for 700 million barrels of commercially recoverable oil.

Subsequent to this, a Liza-2 well was dug nearby (2 miles away) seeking to confirm the Liza-1 findings. The Liza-2 well was drilled to 17,963 feet in 5,551 feet of water. This encountered 190+ feet of oil bearing sandstone in the Upper Cretaceous Formations, leading ExxonMobil to declare: “the Liza-2 well confirmed the presence of high-quality oil from the same high-porosity sandstone reservoirs that we saw in the Liza-1 well completed in 2015”.

Commercially recoverable oil is now estimated at 800 million to 1.4 billion barrels, an amount more than twice the original estimate.

By industry standards, this is a “giant find” and therefore justifies ExxonMobil’s press description of it as: “a world class discovery”. Not surprisingly ExxonMobil and partners have since signalled their intention to drill other exploratory wells, starting in 2016-2017.

Conclusion

Several dynamic features of economic significance stand out about this ‘discovery’. These include 1) its location off-shore Guyana; 2) its size, which classifies it as a “giant deposit”; and 3) its development by foreign interests under agreement with the Government of Guyana.

These will all be addressed as I proceed to pinpoint the key considerations arising out of moving from discovery to production. And here, I will urge that geo-political factors (fixing the oil price and border controversy) will largely determine final outcomes.