Photos by Joanna Dhanraj

The bus stopped and let off its passengers on the ubiquitous red road that runs through the North West District. Unlike other stops, here there is noise; a cacophony of people asking prices, laughing or greeting one another in other languages. Here, the aroma of cook-up and fried fish mingles with the stench of urine from nearby urinals, cigarette smoke and men’s stale breaths laced with alcohol.

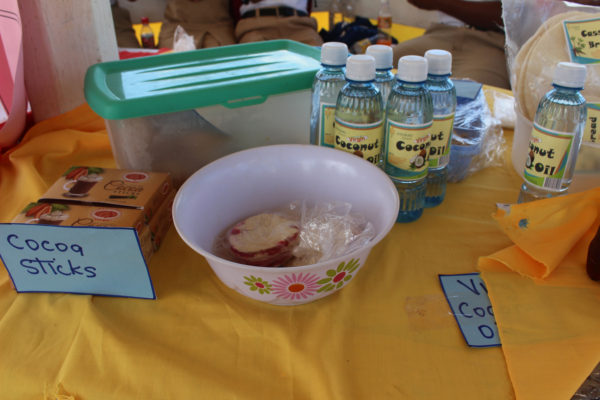

Many of the buildings are painted in different colours but share the same rusty red dust-stained bottoms. The drains are filled with black water and oil floats on the surfaces. Men half-sit in chairs at tables with liquor and cutters; younger ones play pools while sipping beers and singing along to the dancehall music coming from speakers. Straight ahead, a black flowing creek could be seen between the stalls displaying peppers, bora, carrots, bananas and many other fruits and vegetables; snacks, clothes and footwear. Young workers roll barrels through the street headed for Transport and Harbours wharf. This is Kumaka.

An enquiry about the village was answered with directions to the Amerindian Hostel down the street. A wooden bridge would lead you right to it, they said. The long bridge was almost three feet above the ground and the water marks that stained the edge of the ground showed why it was built that high. It was dry and baby crabs scurried into surrounding holes. Precisely at the end of the bridge stood the hostel, which had seen better days. A few pieces of clothing hung on a line in the verandah but there were no other signs of people staying there.

Just at the side were a few other houses. In one of these houses lives Deon Hernandez; originally a resident of Wauna, he moved to Kumaka 16 years ago. He said he moved to be closer to the market where meat, fish, fruits and vegetables are readily available. Though there aren’t many jobs to choose from, there are more here than at Wauna.

“Most people living here are peaceful and kind,” Hernandez said. “The same kind of people I met when I come here, the same kind of people you’ll find now.”

When he lived in Wauna, he used to catch the tractor to come out to Kumaka but when he missed it, he had to walk. He recalled, as a little boy, looking forward for the trip to Kumaka on Tuesdays (one of the market days) even if it meant walking.

Kumaka is the brightest of all the other villages especially on market days, Tuesdays and Saturdays. It is the central village of Region One he indicated. According to him, now that he lives here it isn’t as exciting as it used to be since he’s working here now and life’s become more of a routine but he says coming here meant betterment.

An advantage of living here is being able to farm since it has a relatively clayey soil unlike most other areas where sand can be found and the acushi ants that come with it, cutting the plants at night. However it also comes at a disadvantage since the place floods easily. Hernandez and his family felt the brunt of this until he decided to dig a drain straight out to the creek. Now he isn’t affected by flooding anymore.

Other advantages, he said, are being close to the schools in Mabaruma; his children attend the primary school there. He is also closer to Transport and Harbours wharf, which comes in handy whenever he chooses to travel to Georgetown by ferry.

Hernandez is a construction worker, but he has a side gig carrying fuel to mining areas in Barama with his boat. He also has a kitchen garden which he was working in while he talked with the World Beyond Georgetown.

Most people living here, he added, do small-scale farming of vegetables and ground provision, while others work on public transportation or are caught up with gold mining.

Asked about the Amerindian Hostel, Hernandez said it has been around since 1998. His father had worked there. The building, he said, had been wired but never had access to electricity. Today there is only one person on the premises.

Hernandez stressed that they would like to have access to electricity and potable water in his section of the village, since most of Kumaka already has. He makes do with a generator for electricity and when it doesn’t rain and he’s all out of water he travels by boat to the Hosororo Falls to get some. Added to the list of developments he wishes for better roads as well.

Walking back out on the bridge we see Nidra Joaquin sitting with her granddaughter looking out at the creek from her boutique, which is still under construction.

“I was born in Port Kaituma, raised in Wauna and moved to Kumaka a number of years ago. When I moved to Kumaka I was still a teenager. I moved with my parents. Years ago before we moved, we used to come out by tractor. You live a way better life in Kumaka than in Wauna. If you want something, the market is right there. You ain’t got to come out so far,” Joaquin said.

According to the woman she only recently opened her shop at the back of Kumaka instead of remaining in the market. “I like living by the waterside. Living on the road bad. When vehicles pass it does left the clothes I selling full of red dust. You could imagine them people who got to hang out them clothes after washing it,” she noted.

Joaquin has access to electricity via the power plant in Mabaruma. We don’t get light 24/7. We get light from 5 – 11 at nights and from 5 – 7 in the mornings I would like to have light 24/7. I would like to have [potable] water 24/7 also. We use the rain water. When we don’t get rain we got to go by the [Hosororo] falls.”

Nearby, a Hosororo Primary School pupil was paddling home for lunch all by himself in his canoe; a familiar sight here.

Vendor Stanley Archer is from Georgetown but spends most of his time here.

“When I first came to Kumaka I was working with Transport and Harbours,” he said. “I work on the boats as a super cargo (assistant to the purser or ticket man). I start with Transport since ‘74. I was 14 at the time. Them days [your pay] was 93 cents an hour. I stayed with my brother Dennis Archer whenever I come this side. I started to bring up lil goods, lil DVDs, clothing and start selling in 93 after I left Transport,” Archer said.

This trip he’s been here since July.

“I find the people to be peaceful. The only time you find a problem is when them people drink,” he said.

Business has its good days and bad. But though it may be slow here sometimes, he admits that it works out better here than it does in Georgetown where he left a little shop from which he sells beverages and food stuff whenever he’s there.

“The good thing about living here; you have access to the market filled with fresh organic greens and the air up here is fresh,” he said.

“I never find it difficult living here. The only problem is that you ain’t getting enough light and water and the road is terrible. The other day we went up to White Water Heritage [day activities] and the road was so bad that we took a long time to get there. If we had better roads, we could have spend a longer time at the event. Instead, we had to come away early. We could also do better with a cargo vessel.”

Leaving Kumaka, the bus had to stop to refuel. Imagine the urbanites’ surprise when the tank was filled not by a pump, but from gallon bottles using a makeshift funnel!