The finals of the National Drama Festival (NDF) begins tonight at the National Cultural Centre with one of the plays in the Open Full-Length Category. This festival allows us to continue an interesting study of the contemporary Guyanese stage. One of the notable observations about this theatre is the variety seen in it today, and the way the festival exhibits this in its mixture of old and new plays.

![]() The NDF attracts the leading companies in the country as well as a range of new groups, and these have offered a number of old established Guyanese plays that themselves represent some trends in the local theatre.

The NDF attracts the leading companies in the country as well as a range of new groups, and these have offered a number of old established Guyanese plays that themselves represent some trends in the local theatre.

Take for example, the play Miriamy by Frank Pilgrim directed by Ron Robinson. This play was brought back earlier this year at the Theatre Guild, on the very stage on which it was first created and performed in 1962. It is one of the first plays in the real growth of Guyanese drama in the modern era by one of the founding playwrights of the contemporary drama. It is a comedy which ascended to be one of the foremost of its type in the Caribbean at the time.

As a comedy it has established itself as among the most popular Guyanese plays of all time, having been brought back for several productions over the years and it remains exceedingly popular. It is a colonial drama, a comedy of manners that satirizes a truly colonial society. Although it is such an old play it has held its place as representative of a firmly established trend of popular theatre in Guyana.

As a comedy it has established itself as among the most popular Guyanese plays of all time, having been brought back for several productions over the years and it remains exceedingly popular. It is a colonial drama, a comedy of manners that satirizes a truly colonial society. Although it is such an old play it has held its place as representative of a firmly established trend of popular theatre in Guyana.

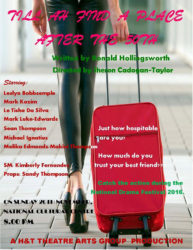

Joining Miriamy is another established play of the popular variety. This one, however, is much more recent. It is Till Ah Find A Place by Ronald Hollingsworth, directed by Sheron Cadogan-Taylor. This one is a situational comedy cashing in on a topical issue – that of a housing shortage that was very topical in the 1990s when it was written. Since then it has been one of the most popular plays in Guyana – brought back repeatedly and always in popular demand.

A number of sequels were written because of that popularity, in the same comic vein. Additionally, it was made into a film. Till Ah Find A Place also represents the trend of popular comedies in Guyana, as well as topical plays. This type of drama may be described as carpe diem since they seize the moment when some issue or prevailing situation commands the public’s attention and the playwright pounces on it to do a play and strike the audience while it is hot.

Some of these very dramatic types were seen in the preliminary rounds of the NDF, with some of them to be repeated in the Finals. For instance, there is Tenement Yard by Jemima Holmes, which represent a recent upthrust or resurgence of plays of its type in Guyana. The NDF itself saw one of them last year – Crack Jokes by Odessa Primus, while another appeared in NDF 2016 – A Scheme Yard Affair by Runasi Perry. These plays belong to the ‘Caribbean Back Yard’ tradition in the theatre.

Tenement Yard is a new play which reflects renewed interest in the form by new contemporary playwrights in Guyana. It is unbridled, often ribald humour, a trendy, popular play set in a tenement yard. There are stock characters and typical domestic situations that are tailor made for laughter.

The stock characters always reappear in the yard setting ever since the rise of this form in the Caribbean in the 1950s. This one follows the old tradition, as well as the new developing mini-trend in Guyana where this kind of play is becoming popular.

Other plays use humour to a lesser degree because, though sometimes funny, they belong to other types of drama which do not clearly represent any particular trend in Guyana. Collision is a love story, one that may be called a romantic comedy, written by Lorraine Baptiste and directed by Linden Isles.

This one also draws on topicality since its setting is a common one in which members of a Guyanese family return home from their USA residence to bury a grandmother. The situation that they find themselves in contains a touch of both humour and romance. Three women are the focus. Twyla Sealey plays the humour in a typical earthy, uninhibited neighbour whose role is to thrill the audience, which she emphatically did. Another is the lead, Melinda Solomon in a steady role that sometimes called for deep emotional reflection.

The role that combines all was the romantic lead in which Nathaya Whaul impressively succeeded in many emotional changes, much agonising as well as her own moments of humour.

The other play in this group that was outstandingly funny was D-O-T Com written and directed by Clinton Duncan, which is, however, to be placed in quite a different category. It was hilarious, but is a kind of a sci-fi satirical comedy – a fantasy – creating a very funny situation out of current computer technology. It is a slick, snappy piece which was noted for the acting of a very effective quartet – Sonia Yarde, Michael Ignatius, Leslyn Bobb-Semple and Nicholas Singh.

The types of comedy continued to vary with another play by Baptiste: The Sweet Taste of Lemon. This, too, demonstrated the popular comedies that have dominated the Guyanese stage for many decades. It is the picture of a home that deteriorated into dysfunctionality, touching on the social ill of drug dealing, corruption of youth and the value of a concerned neighbour. It made use of farce and slapstick to create a comedy in which the rogue is exposed, there is moral rescue and all ends well.

Quite the opposite of those were the dramas that depart from the norms to experiment with different kinds of theatre. They were the avant-garde, post-modernistic types. Plays of this nature have been rising in Guyana in the last five years and showed that there are new playwrights in the country whose thinking departs from the realism which dominates Guyanese theatre.

An example of these is Subraj Singh’s Masque, the second play in The Rebellion Trilogy. This is a very intense drama with multiple interests and preoccupations. It is post-colonial, post-modernist, feminist and ritualistic theatre. Masque tells a historical tale of the Amerindians in Guyana from a pre-Columbian society to the present. Its main setting is a traditional nation of indigenous people; it is a tale of war, conquest, acculturation, betrayal, blood and vengeance.

The play is exceedingly violent and is a virtual revenge tragedy, dramatizing the tragedy of a whole nation of indigenous people and their contact with the Europeans, which is mainly confrontation and conflict, but slightly tempered by a symbolic inter-ethnic love story.

A number of performers including Lorraine Baptiste as lead actress, spirit of vengeance and dancer, Nirmala Narine in a non-violent, tempering romantic role, LeTisha Da Silva who had to play a mixture of deceit and seductive temptress, Tashandra Inniss as a probably uncharacteristic female warrior hunting for blood and revenge, Ackeem Fraser, Onix Duncan and others played out a drama dominated by violence.

Not far removed from this was Baraka’s Revenge by Melinda Primo Solomon, a mixture of dream fantasy, post-modernism, post-colonialism and theatre of ritual. It is mythical, drawing on legend, folklore, myth and history and using as a frame the mysteries behind the baccoo in the bottle in Guyanese folklore. This is linked to the African past which is dramatised in flashbacks and ritual.

This play has its share of violence, treachery and power in a traditional African society before the trans-Atlantic slavery. Its post-colonial element has to do with a sub-story of the beginnings of this other tragedy. The lead actress Kimberly Fernandes is at the centre of this drama, moving between the past and the present while having to be the strong warrior queen at one moment and the girl urgently concerned about the safety of her friends in the next. She is joined in this by Rae Wiltshire, an effective voice of reason and wisdom for the tribe, Ackeem Joseph, Nelan Benjamin and others.

The Final Chapter by Duncan is another in the avant-garde theatre. It is an Ionesco-type drama with very strong suspensions of belief, existentialism and a little touch of the absurd. Characters move in and out of fiction and reality, a story being written and writing itself. It is a clever and very intense drama with a team of performers working exceedingly well together, including Fernandes, Whaul, Wiltshire, Colleen Humphrey and Joseph.

Don’t Ask Me Why by Wiltshire is yet another type of departure as it explores a daring and controversial rewrite of the Christian creation myth. It is existentialist and very searching, playing with sexuality, gods, devils and the origins of mankind and even the original ‘sin’. It uses ironic reversals, especially between God and the Devil, played by Humphrey and Nickose Layne.

On the other side of the stage are the plays of social realism with elements of melodrama, suspense and variations of nursery rhymes. Jack and Jill (The Modern Epilogue) by Lloyd Thomas presents the last of those in its tragic tale of abuse, families falling apart and the motif of the wicked stepmother believably played by Tikoma Austin.

Blind Success by Odessa Primus has quite a message in its story of a blind boy inspired to scholastic success but torn between that and grief in a performance featuring Primus herself with support from Leon Cummings. The Ex by Sheron Cadogan-Taylor thrives on an element of suspense and intense melodrama and a touch of terror, carried mostly by Mark Luke Edwards.

One memorable effect in this play is the integration of dance in a real way as its Prologue is a very effective pas de deux by Whaul and Keon Heywood. Still another type is a story featuring children in a Sunday school finding