Birds chirp cheerfully and the soothing sound of the waves softly swishing ashore hide the horrors that exploded here decades ago.

No visible signs remain of the Cubana 455 tragedy save for a solemn stone obelisk erected in 1998 at the aptly-named Payne’s Bay, St James, on which the title of the youngest passenger, the nine-year-old Guyanese girl, Sabrina, is carved at the top of one stern facade but only as a male misnomer and in a symbolically severed surname – Harry Paul. Nearly five miles out, what is left of 57 other people and their ruptured tomb lie hidden 1 800 feet under the sparkling blue sea.

Yet 40 years on, former pilot Jim Lynch clearly remembers the sharp stench of jet fuel. It was everywhere that indelible day, sickening slicks of it seeping among the strewn plane wreckage and human remains floating in the calm expanse, when he joined a Barbadian Coast Guard cutter and they sped across from the south side on that surreal, sunny October 1976 afternoon following the downing of the Douglas DC 8 airliner.

Yet 40 years on, former pilot Jim Lynch clearly remembers the sharp stench of jet fuel. It was everywhere that indelible day, sickening slicks of it seeping among the strewn plane wreckage and human remains floating in the calm expanse, when he joined a Barbadian Coast Guard cutter and they sped across from the south side on that surreal, sunny October 1976 afternoon following the downing of the Douglas DC 8 airliner.

“At first I did not see anything unusual, but there was a very strong smell of kerosene – jet fuel. Then I noticed the bodies draped over the gunwales of the other boats and the occasional body part and personal possessions in the water.”

A young Air Traffic Controller (ATC) attached to Seawell Airport at the time, Lynch was enjoying his day off and in Bridgetown, when he heard news about the crash of the big four-engine jetliner just off the scenic west coast and curving Paradise Beach.

“I telephoned Ted Went, then Director of Civil Aviation for permission to go out with the Coast Guard as a representative of Air Traffic Control and he agreed to call them and ask the last boat going, to wait for me – there were about three Coast Guard boats in all and the others were already on the scene,” he said in a recent online interview.

Jim rushed to his father’s office, borrowed Dad’s car and raced for the Coast Guard Station near the popular fishing village of Oistins – which many tourists love because of the fabulous fish fry and the fact that the beaches are on the direct flight path of the jets swooping down to land at the nearby airport now termed Grantley Adams after the first Prime Minister.

That day, Pilot Wilfredo Perez did try really hard to make it back to the familiar runway and save his 72 passengers and crew. The valiant Captain’s words are immortalized in aviation history, his voice astonishingly calm and clear on the famous recording, “Seawell, Cubana 455” he suddenly calls in politely at about 1:23 p.m, and then as the Air Traffic Controller (ATC) acknowledges him, he continues in thickly accented English, quavering just a bit: “We have an explosion! We are descending immediately! We have fire on board!”

“Cubana 455, are you returning to the field?” the Barbadian officer asks pensively. “Aqui, Cubana 455. We are requesting immediately – immediately – landing!” Perez raises his voice slightly.

The Controller responds, “Cubana 455, you are cleared to land.” Perez replies with one word, “Roger” and then he abruptly orders in his native Spanish,

“Cierren la puerta! Cierren la puerta! (Close the door! Close the door!).”

Perez had already turned around the crippled plane with its burning breach, and been well on his way in, when a second powerful bomb concealed in a Colgate toothpaste tube and left by Venezuelan, Hernan Ricardo Losano, 21, detonated in the washroom at the tailend of the plane.

The radio crackles, the Controller comes on at 1:27 p.m: “Cubana, we have full emergency on standby.” But this time, it is the unforgettable, urgent and ultimate utterance of the co-pilot: “Eso es peor…!” he yells in alarm, “Pegate al agua, Felo! Pegate al agua!” (That is worse…! Hit the water, Felo! Hit the water!), a reference advising Perez, using his Cuban nickname, to avoid slamming into the crowded coastline, saving countless more lives on the ground. The experienced pilot agrees, instantly turns the huge jet and steers it away from the small island, rising high and then hurtling in a death descent towards the ocean with the terrified travellers screaming frantically in the five minutes of hell since his initial alert.

“Cubana, este es Cari-West 650. Podemos ayudar en algo?” a nearby aircraft queries in concern, “Can we help you?” But there is silence.

Jim recalled, “When we got out to the site, off the west coast, there were about four other fishing and pleasure boats around, apart from the Coast Guard.”

“While putting on a wet suit handed to me by a Coast Guard sailor, I also noticed what appeared to a school of sharks cruising under the water around the boats,” and from then on he stayed watchful, as “I spent most of my time down the ladder at the back of the largest Coast Guard boat fishing out pieces of the aircraft and handing them up to the rear deck – I had gone out there to make a contribution, not to sightsee.”

Some of the lengths were too massive to pull out by hand. Lynch, a tough, hard-talking Barbadian originally from Christ Church, later qualified as a pilot and flew planes, becoming a seasoned operator for Tropic Air, Air British Virgin Islands (BVI), Carib Aviation and LIAT.

“I only collected aircraft pieces. No body parts came anywhere near the boat I was on the back of, but by then it was (a while) after the actual event. I never saw any faces of the deceased, just bodies – the heads of those draped over the gunwales of the other boats were on the inside,” he reports straight forwardly.

Now retired and living in Canada, Lynch recollected: “in the nearest pleasure boat – with at least one body hanging out of it – there was a man in the front striking match after match to light a cigarette, and none would stay lighted. Immediately we all started shouting at him ‘NO SMOKING!’ – because there was a real chance the kerosene vapours would also light and there would be a massive uncontained flash fire over the water.”

One witness from the “Jolly Roger” sailing ship, informed an official Inquiry that he spotted the stricken jetliner “when it was about two and a half miles away at about 400 feet altitude as it was proceeding inbound from the west towards the shore.”

He disclosed “it seemed to be unstable with the wings dipping and (thick) black smoke coming from the number one engine. The aircraft then went into a steep 80 degree climb to about 1 000 feet, fell off on its right wing and crashed (intact) into the sea.”

Some 1 400 pounds of wreckage were recovered including portions of the cabin interior, control services, nose gear, main gear and walls of the washrooms, among them the inside segment of one lavatory covered with soot, heat damaged and with numerous punctures of its surface.

A Cuban explosive expert who was not named in the diplomatic cables studied, maintained at the Barbados Judicial Inquiry (BJI), that there were two separate blasts. “He stated that the evidence indicates that the first explosion took place near rows 10 or 11” and the other near or inside the economy class lavatory, citing conclusive evidence based on chemical and metallurgical examinations. Control of the plane was lost due to catastrophic control cable damage.

“Twice he mentioned the CIA (United States Central Intelligence Agency) stating that they were experienced in explosive sabotage devices and trained personnel how to make and use them,” American Ambassador to Barbados, Theodore Britton wrote in a message to the State Department.

Among the 15 or so broken bodies pulled from the ocean, were the shattered remnants of Sabrina, who had been sitting with her doting grandmother, Violet Thomas and aunt, Rita Thomas near to where the first incendiary C4 device casually left by Losano’s accomplice Freddy Lugo, in a camera bag under a window seat blew up and started a blaze that tore through to the outside wing.

According to some reports, the Thomases and their slim, pig-tailed charge had missed their original connection at Timehri International Airport and were hastily put on the next flight out, the Cubana, in an attempt to get them to Jamaica in time for their long onward journey to Canada, where the child was due for medical treatment.

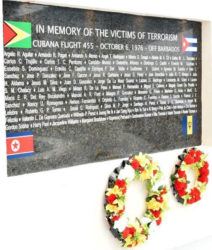

The trio was among 11 Guyanese murdered in the terrorist attack which also killed 57 Cubans and five North Koreans. Three of the latter delegation had fatefully postponed their departure, to meet with Foreign Affairs Minister, Fred Wills.

The BJI, that November, heard from the unnamed Chief Aircraft Engineer for Air Canada stationed on the island.

He coordinated and assisted in the examination and identification of recovered parts and components of the insured aeroplane, leased from Canada. He too identified rear fire damage and concluded that bits and pieces of metal propelled at high speed had shot into seat cushions, 2006 declassified American cables state.

A Jamaican Coast Guard Commander on duty with the Barbados Coast Guard, who helped pinpoint the two contacts of sonar location on October 24, by “dead reckoning” after much “conflicting” suggestions from the public, testified “there was no significant separation of wreckage, personnel or floatage found.”

It was all resting in a quiet area of the Bay, a deep grave off Barbados’s rich “Platinum Coast,” in which the pair of severed main chambers of the plane plunged to permanent place.

ID despairs how come it took 36 long years, amnesia and much squabbling for Guyana to build a basic wall memorial, in 2012 at the University of Guyana, to those who died in the Cubana bombing and the name of at least one local victim, little Sabrina, whose mangled remains are buried in Havana’s immense Colon Cemetery, is still listed wrong, inexplicably as a man again – “Harry Paul.”