By Michelle Yaa Asantewa

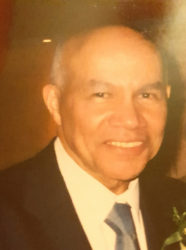

Michael Abbensetts, who inspired a generation of Black British writers and actors by writing strong, independent and believable black characters, challenging racial stereotypes, has died aged 78. Born in Guyana in 1938, he migrated to the UK in 1963 and became a British citizen in 1974. He is credited as being the first black British playwright to be commissioned by the BBC to write a series. Empire Road (1978-79), which despite its success, ran on the BBC for only two seasons, and was the first black drama series to be screened on British television. Nothing of its kind has been screened since.

Abbensetts was born in Georgetown into a middle class Guyanese family of mixed African and European heritage. His father, Neville John Abbensetts, was a doctor, his mother Elaine was a homemaker. Abbensetts once described his father as ‘a kind of Victorian character’ who was saluted by the police; such was the respect shown in those days to people like his father. He attended Queens College (1952-56) before moving to Canada, where he went to Stanstead College in Quebec and later studied at St George Williams University, Montreal (1960-61).

Inspired by a performance he saw in Canada of Look Back in Anger, by John Osborne, he decided to become a playwright. When he arrived in Britain in the early 60s there weren’t many black playwrights.

Ambitious and mindful that his decision to become a writer and not a doctor or lawyer had disappointed his father, he was determined to get his plays staged. His first play, Sweet Talk was performed at the Royal Court in 1973. Don Warrington and Mona Hammond played an unhappy couple, struggling with the economic, emotional and social demands of family life as Caribbean migrants. The success of this play, which won the George Devine award, led to his appointment as resident writer at the Royal Court and his first television play, The Museum Attendant (1973).

Abbensetts had worked briefly at the Tower of London as a security guard and translated his experiences into this play, which had both black and white characters. Critics recognising that he ‘could write white as well as black characters’ began to take notice of his work. He credits some of his success to a good agent who represented a lot of well-known directors and writers and who had asked some of the high profile white directors, notably Stephen Frears to direct some of his plays.

Abbensetts was asked by a young producer, Peter Ansorge, then beginning his career at the BBC, if he had any ideas for a TV series. He came up with Empire Road, which was set in a fictional location based on his experience of living in Birmingham. The lead characters, played by Norman Beaton (Guyanese) and Corinne Skinner Carter (Trinidadian) were styled on an uncle and his wife. Although it was considered a black version of the long running British Soap Coronation Street, Empire Road with its fully black cast was making a statement about the lack of black people on British TV.

Norman Beaton’s character (Everton Bennett) was called the ‘godfather’ which identified him as a respected leader in his community to whom others took their problems. Each episode was set up to explore a particular issue experienced by members of the Thornley community. In one of these single story episodes, Beaton skilfully provokes the migrant ‘question of belonging’ when in a progressive fit of drunkenness he and his brother-in-law (played by Joseph Marcell) discuss whether they would ever be accepted in the UK.

One of his most successful TV dramas, Black Christmas (1977) advanced ‘questions of belonging’ and redefining cultural space by exploring the consequence of mental health as experienced by black people trying to adapt to life in Britain. In this one-off drama for the BBC, ‘whiteness’ through the television is foregrounded against the pretentions of a perfect Christmas which a recent migrant family to the UK were attempting to celebrate.

Carmen Munroe, playing the lead had cooked Christmas dinner which included the traditional rum drenched Guyanese/Caribbean black cake but all was not well. Janet Bartley, playing Munroe’s sister-in-law was in a state of mental depression, brought on by the difficulties of trying to adapt to life in the UK and cope with her husband’s infidelities with white women.

It has been described by critic Stephen Bourne as ‘one of the best television dramas of the 1970s.’ This is perhaps because Black Christmas was ahead of its time. Nothing like it has since been featured on British television which so intimately explored the theme of mental depression, resulting in high numbers of black people in psychiatric hospitals in the UK. In writing this drama, Abbensetts once said he “wanted to deal with the fact that there are some black people in our society that we don’t seem to talk about.”

Between 1983-84 Abbensetts became a visiting professor at Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, USA where he met his first wife, Connie, a lawyer from Texas. When Connie died of cancer in the late 1980s Abbensetts returned to the UK. In 1994, Channel 4 aired the mini-series Little Napoleons, which reflected an overriding quality in his work to produce feisty, confident and aspiring black characters. He met these ‘larger than life’ characters in real life, Norman Beaton being one of them, for whom he wrote many of his leading roles. Beaton died in 1994, cutting short their lifelong friendship and signalling the end of a prolific era of writing for Abbensetts.

A collection of his works, Four Plays was published by Oberon Books in 2001. Regarded by many as an extraordinary talent, Abbensetts’ work gave voice to the lives of black migrant communities in the UK and answered his own anxieties, not only about racial identity and belonging but about the worth of a writer. As observed by Jessica Phillips, he had, after all achieved notoriety and was ‘better known’ than his father, ‘merely for writing plays.’

He remarried in 2005 to Liz Bluett and though they separated after a few years they never divorced. Abbensetts is survived by his only child, Justine Mutch, from a relationship with Anne Stewart prior to both marriages, his grandchildren Danielle and Sean and his sister, Elizabeth.

He had been suffering with Alzheimer’s disease for a number of years, which led to him living in residential homes in his later life. He contracted an infection from which he never recovered a week before his death on Thursday 24th November 2016. His funeral was held on Wednesday, December 7, 2016.