To mark the anniversary of Martin Carter’s passing in December 1997, Gemma Robinson looks at Carter’s work on independence from 1966.

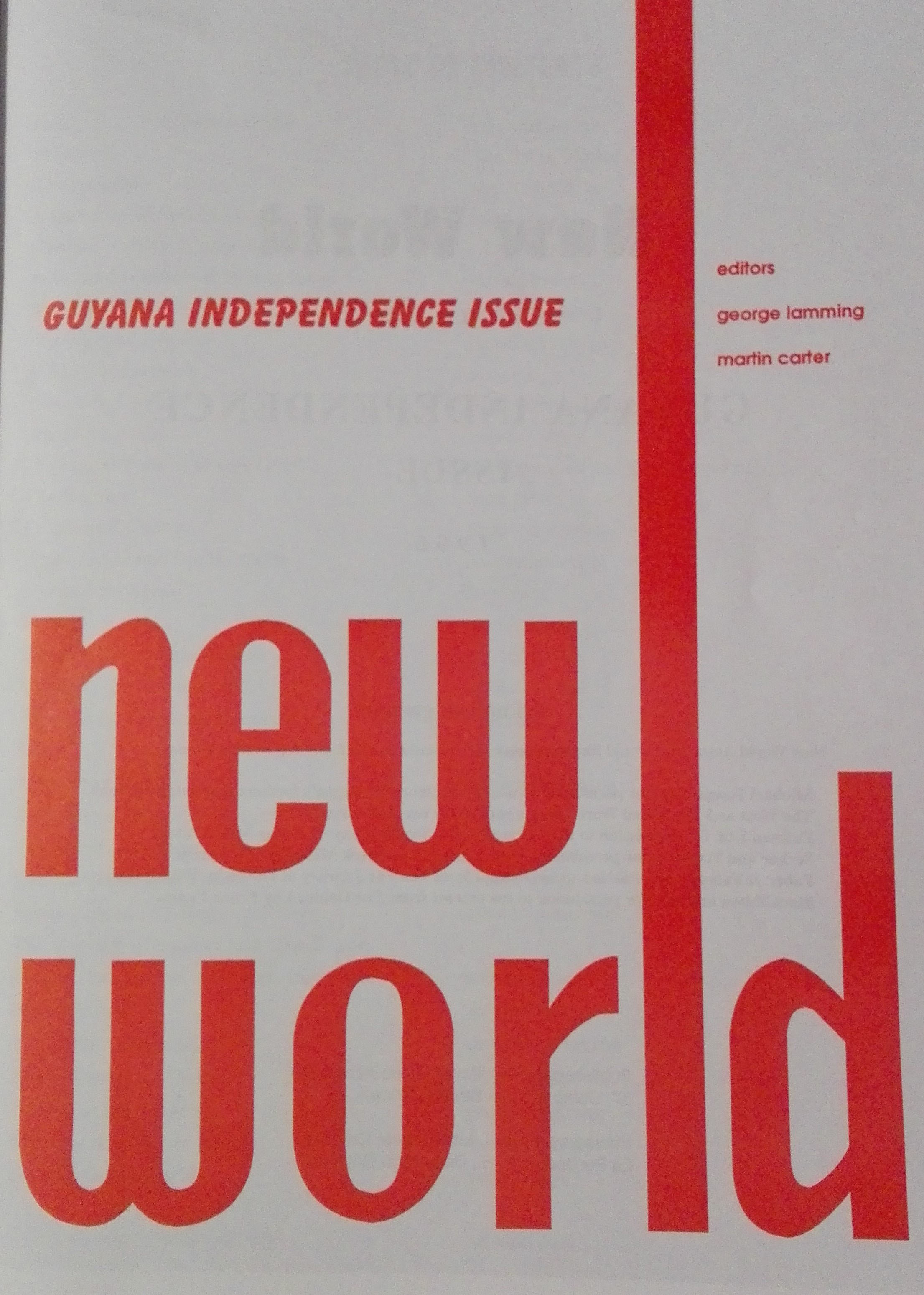

In 1965 David de Caires and Miles Fitzpatrick invited Martin Carter and George Lamming to edit a special issue of the journal, New World. The goal of the New World group was to debate the political and cultural future of the Caribbean. This special issue would be dedicated to Guyana and coincide with the formal declaration of its political independence. For Carter and the Barbadian Lamming it was a unique opportunity to explore the links between Guyanese politics, national identity and culture. The two took up the invitation and the New World:

Guyanese Independence Issue included work by Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, Wilson Harris, C L R James, Walter Rodney, Nicolas Guillen, Sydney King (now Eusi Kwayana) and Ian McDonald. It stands today as an astute collection of voices dedicated to freedom-thinking.

In the Foreword then prime minister, Linden Forbes Burnham, acknowledged the importance of independence:

To many, Independence means merely the formal conceding of political and constitutional power by the imperialists to representatives of the local populace. [. . .] Few, however, address their minds to the need for cultural and artistic independence; to the need for formulating cultural and artistic goals for the new nations.

In presenting Guyanese independence as a cultural, as well as a political condition, Burnham added his voice to debates, led by A J Seymour in Kyk-Over-Al, about the distinctive nature of cultural independence in Guyana. Burnham continued that ‘we must acknowledge the urgent and essential role of the intellectual worker in the process of transforming our societies and nations’.

In the light of the polarising politics of the twentieth century, we might want to place Burnham’s statement alongside the testing question of literary critic, Gordon Rohlehr, who asked in 1972 ‘how far the politics of independence has kept in tune with the wholeness of creative sensibility and enquiry, which one can feel in our artists and scholars’. Wholeness here is an important word because it brings to mind its opposite. What was the task of creating a nation-state? After imperialism, it could never be the representation of only selected interests, but must be dedicated to understanding and reimagining the society for all. To Rohlehr, the documentary and imaginative commitments of Caribbean art and scholarship presented ways of seeing the world that were alternatives to divisive partial (maybe even party) perspectives.

To see and present the wholeness of Guyana was a demanding editorial task. Four themes guided the editors – ‘the land and the people’, ‘a backward glance’, ‘ours and elsewhere’, ‘voices from the future’ – focusing attention on Guyana as a nation being created out of a complex past. Party politics, however, were never far away. Lamming remembers that he and Carter agreed that the publication should ‘cut across all the party lines’. The decision to include the opposed politicians, Linden Forbes Burnham of the PNC and Cheddi Jagan of the PPP, was one way to tackle the tensions in this new nation and to see its complicated wholeness. Jagan’s autobiographical piece was the first article in the issue. Lamming held that it was only through Carter’s continuing relationship with the two men that the editors were able to unite, if only in print, two politicians who would remain irreconcilable.

But as one cultural bridge was made other gaps almost inevitably appeared. No women contributed to the Guyanese New World issue. Amerindian perspectives were visible only through Donald Locke’s designs. The impressive chorus of voices was pan-Caribbean, multi-disciplinary, but it was a fraternity. Wider-ranging questions about gender and ethnicity were not taken up in these pages, and what the viewpoints of say, Jessica Huntley, Janet Jagan, Edwina Melville, Rajkumari Singh and countless others, could have brought to this moment remain out of sight.

Was wholeness then an impossible dream, in print and in politics? It is certain that the partial perspectives of editors and contributors added up to a complicated total, but they could not cover the complicated whole of Guyana’s past, present and future. Yet understanding and reimagining that complex unity remained the task. Carter’s own contributions to the collection confronted how we might see the world as unified. The line, ‘All are involved!’, rang out from Poems of Resistance (1954) but countering this was:

Rude citizen! Think you I do not know

that love is stammered, hate is shouted out

in every human city in this world?

(‘After One Year’ (1964))

These tensions between unity and division, love and hate, can seem very contemporary. They were uncompromisingly explored in the essay that Carter wrote especially for New World Quarterly: ‘A Question of Self-Contempt’. The essay sketched his political awakening in 1950s with the exacting imagery of the poet: ‘And every Sunday night a meeting in an unpainted hutch with grey dust like history’s night-soil between the creases in the floor. Sometimes no more than five of us. Five bewildered creatures on a Sunday night repeating ourselves like desperate obeahmen’. In this tale of political origins, Carter did not shy away from the conflicting emotions of optimism and despair.

To Carter these were ‘great days’, but they were also tormented by concerns about the world and the possibility of changing it for the better: ‘Outside the world. Dog dung in the street. A black man in South Africa. Love beneath the stars. Firelight in the cane-pieces. Degradation, absolute vomit. Bed. Same tomorrow. Tomorrow again. Tomorrow always’. Carter’s lens focused back and forth between the details of life near and far. Tomorrow – that evocative word for the revolutionary mind – was offered up, not as a promise of better times, but as a future denied or a future that had already failed.

Yet Carter would not turn away from seeking a better world or trying to understand his place in it. He recognised that his colonial status in an imperial world was not a neutral fact, but a traumatic challenge to his personal identity: ‘Self was here in visible location, aware of the datum and exigence of land and community. But who was my? Who self?’ In the essay Carter went on to trace how imperial thinking, with its formulations of power and race, will always be at odds with the personal and the political aims of freedom-thinking. He remembered being told a story:

of a man, who, applying for the post of hangman, had written the Superintendent of Prisons to say that since he was a little boy it had been his ambition to become a hangman one day.

The symbolism of the anonymous hangman and his noose has been used historically to reinforce a notion of blind justice, but within a colonial society with a plantation past, the roles that people dream for themselves are always caught up in that history. The story of the would-be hangman of British Guiana was symbolic for Carter as part of a larger cultural story about the ‘degradation’ of possibility and hope for society. The young Carter, only 23 when the PPP was founded, sought another world, and in doing that he questioned our understandings of identity as well as society.

Thirty-three years after independence Lloyd Best, the Trinidadian intellectual, revisited the legacy of the New World Group and the independence issue. He wrote that ‘the effect of putting out journals, booklets and pamphlets was to emancipate voices’. The story of the Guyana Independence issue both supports and complicates this claim. David de Caires remembered the discussions surrounding its publication:

Well I was the hard man because I was the man who was actually in touch with the market, paying the bills and I knew where copies go. And I said I thought we should print a thousand, whereupon Lamming, who has this very Oxford accent: ‘O my God! What a travesty man!’ he said, ‘I’d sell 5000 outside Lords in London in one afternoon’.

Lamming imagined an enthusiastic audience wanting independence writing, an audience not just in Guyana but across the globe. It was an inspiring example of freedom-thinking in practice.

In the end de Caires was persuaded by Lamming’s winning enthusiasm, but they did not sell all the copies: ‘Suffice it to say we eventually printed a big number. It was about 10,000, it could have been more and I never got paid for all the copies we sent abroad. I think we were all overruled by George’s extraordinary optimism’.

If we wanted to, we could find in the unsold, unread copies of New World a symbol of the challenges faced by independence movements to create whole communities. But that would fail to see the importance of freedom-thinking and the hope that fuels it. Although independence might be gauged as a fixed moment in time, we also know that the acts that create communities can take place over long chaotic periods, preceding and following any formal declarations. Carter’s and Lamming’s independence work – and the enthusiasms, doubts and debates that appear in the pages of this special issue – did not escape failure, but nor did they abandon optimism. This apparent contradiction is present in Carter’s poetic sensibilities as well. In ‘Black Friday 1962’ he writes: ‘in despair there is hope, but there is none in death’. Carter reminds us of a difficult balance. Hope and despair are twinned emotions in our human lives. His work urges us to find a balance between these feelings as we try to oppose past hate, and live and love together in a new world.

Gemma Robinson is the editor of University of Hunger: the Collected Poems and Selected Prose of Martin Carter (Bloodaxe).