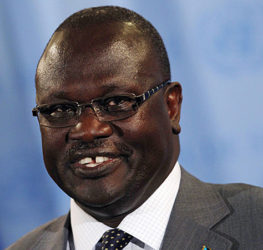

JOHANNESBURG, (Reuters) – South Sudanese rebel leader Riek Machar, who fled to Democratic Republic of Congo in August after fierce fighting, is being held in South Africa to stop him stirring up trouble, diplomatic and political sources said yesterday.

Removing Machar from circulation would be a blow to his rebel SPLA-IO faction in its three-year war with President Salva Kiir’s mainstream SPLA, and could sway a conflict the United Nations fears is tilting towards genocide.

Over a million people have fled the world’s youngest nation since conflict erupted in late 2013 when Kiir, an ethnic Dinka, fired Machar, a Nuer, as his deputy. The cross-border exodus is the largest in central Africa since the 1994 Rwanda genocide.

In South Africa, a well-connected regional political consultant said Machar was being held “basically under house arrest” near Pretoria with his movements restricted and his phone calls monitored and controlled.

“If he wants to go to the toilet, he has to hand over his phone and a guy stands outside the cubicle,” the source said.

Foreign ministry spokesman Clayson Monyela denied Machar was being held against his will, describing him instead as a “guest” of Pretoria as South Africa tried to prevent the civil war sliding into genocide.

“Him being our guest here is part of our responsibility as a mediator,” Monyela said, adding that it was “difficult to predict” the duration of his stay. “It’s very hard to put timelines on these peace and security situations.”

Dickson Gatluak, a Machar spokesman in Ethiopia, denied there were any restrictions on Machar and dismissed the reports as misinformation. “This is not true. It’s baseless and unfounded,” Gatluak told Reuters in Juba.

“Dr. Machar is safe and doing his normal duties as usual. He is communicating to us daily, including his field commanders in the entire country.”

Attempts by Reuters to speak to Machar in South Africa via his spokesman there were unsuccessful.

Kiir visited his South African counterpart, Jacob Zuma, on Dec. 2 to “review… the latest regional political and security developments on the continent”, according to a South African statement that gave no further details.

Refugee accounts and human rights reports point to both sides in South Sudan targeting civilians along ethnic lines.

Machar reached a peace deal in 2015 with Kiir but the agreement fell apart in July, leading to several days of intense fighting in Juba, the capital of the five-year-old nation.

Machar himself was wounded and after fleeing to Congo went to Sudan – a long-term supporter of his rebel faction – for medical treatment. He then turned up in South Africa in October for more treatment.

A diplomatic source said the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, an eight-country East African group, had asked Pretoria to make sure Machar did not leave. The United States, Britain and Norway had supported that request, the source added.

“He keeps going back and mobilising his people and stirring up problems,” the source said. “It’s best to keep him here for a while.”

Machar flew two weeks ago to Ethiopia, which has also tried and failed as a mediator, but was refused entry and given a stark choice: go back to South Africa or get dumped in Juba, to be left at the mercy of Kiir’s troops, two of the sources said.

“The Ethiopians told him there were two planes sitting on the tarmac – one heading to Juba and one heading to Joburg – and told him he had 10 minutes to decide,” the political source said. “It didn’t take long.”