The reality

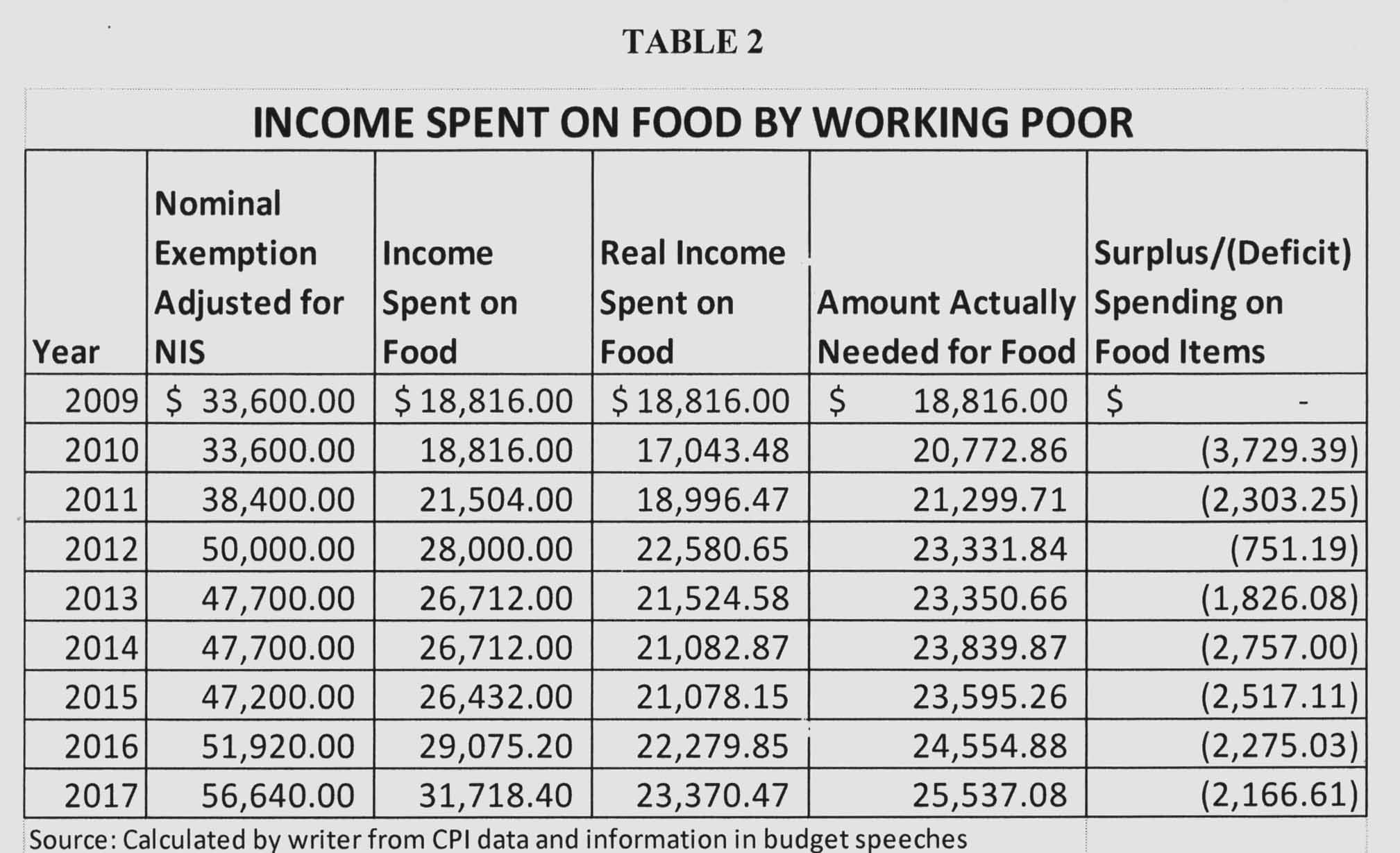

One could see from the data presented in last week’s article that the intention of the government is clear. It wants to see the people of this country better off than they were before. As a consequence, it has taken steps to reduce the burden of the working poor by increasing the exemption and reducing the tax rate in the 2017 Budget. Anyone who cares about the welfare of their fellow Guyanese could see the wisdom of making such a move. When the effects of the two courses of action are combined, the working poor will no longer have to carry the same proportionate burden as the well-off in financing the programmes of the government. Even though the exemption is $60,000, the reality for the working poor is that anyone in that category will have to be earning in excess of $63,559 in order to start incurring a tax liability and that liability will be minuscule, being less than 20 cents on the entire income. The tax relief extends well beyond the exemption amount. Income would have to be as high as $66,050 before anyone would have to pay as much as one per cent of his or her monthly income in taxes. These steps expressed in the budget ought to make the working poor happy, yet the laudable actions seem to be generating unfavourable reactions. They appear reluctant to believe that positive changes have come their way. Table 2 below offers some insight into what might be the problem.

the working poor will no longer have to carry the same proportionate burden as the well-off in financing the programmes of the government. Even though the exemption is $60,000, the reality for the working poor is that anyone in that category will have to be earning in excess of $63,559 in order to start incurring a tax liability and that liability will be minuscule, being less than 20 cents on the entire income. The tax relief extends well beyond the exemption amount. Income would have to be as high as $66,050 before anyone would have to pay as much as one per cent of his or her monthly income in taxes. These steps expressed in the budget ought to make the working poor happy, yet the laudable actions seem to be generating unfavourable reactions. They appear reluctant to believe that positive changes have come their way. Table 2 below offers some insight into what might be the problem.

Assumptions

The data in Table 2 are based on the exemption thresholds for income tax that were granted since 2009. The preparation of the data relied on several assumptions. One assumption was that the exemptions represent a reasonable estimate of the income of the working poor. Another assumption was that in global comparisons the poor spend an average of about 56 per cent of their income on food at the high end and that allocation of income was correct in the case of Guyana. In addition, it is assumed that most of the food purchased by the working poor does not attract VAT and that the non-food items that they buy attract VAT. Finally, this writer projects a worst case scenario of inflation running at about four per cent in 2017. One must keep in mind too that the private sector business strategy does not enable all of the working poor to earn money at the level of the exemption threshold and therefore many workers could be worse off than reflected in the Table above.

The last column of Table 2 is most instructive. It suggests that, even without the burden of VAT, many people earning a minimum wage and less had to borrow money to eat. The data in the Table enables one to see that the plight of the working poor was evident long before 2015 and was rapidly deteriorating after 2012. Guyana was one of those countries that had committed itself to cutting poverty in half by 2015 under the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). It made progress, but clearly needed to do more than it had done. That failure has left many Guyanese unable to take care of themselves. By 2014, the working poor had to find nearly $33,000 extra just to eat. Many were forced to lean on family members or perhaps call on friends for help. In some cases, the working poor might have even gone into debt to survive.

More desperate

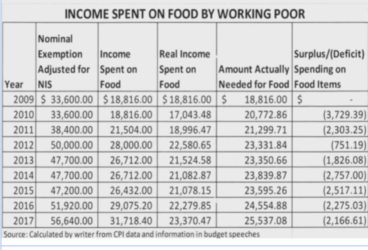

Matters appeared to be even more desperate where non-food items were concerned as can be seen from Table 3 above. The deficit for non-food items continued into 2015, even though it began to improve with some of the measures taken by the new administration. An item with an important impact is the value-added tax or VAT. At 16 per cent, VAT has contributed to the real deficit of the poor reaching as high as $75,000 in 2014. Though things continue to be tough, the deficit for non-food spending had fallen to its most manageable level yet in 2016 and was projected to improve further in 2017. However, things remain very difficult for the working poor when total spending is accounted for. They will still be short an estimated $22,000 in 2017 even with all the favourable changes planned.

As things stand now, the working poor will remain in a state of permanent dependence if further action was not taken. The reluctance to believe that positive changes have come their way might stem from a holdover feeling about the difficult past years where it looked as if there was no glimmer of hope for them. Under such desperate circumstances, people can easily be seduced into believing that better could be had by travelling abroad or engaging in some type of illicit activity.

The budget of 2017 is trying to ease the situation by altering the contribution that the working poor is asked to make towards government spending. It is one of several strategies that must be employed to bring relief and protection to that class of workers, and by extension all Guyanese. The government needs to have better information about the income and expenditure of families so that more effective policies can be designed and implemented in the future. While people might treat it as another item of government expenditure, the labour force surveys that are planned for 2017 and beyond represent an important initiative in the fight against poverty. That exercise, along with the establishment of a Poverty Measurement and Analysis Unit in the Bureau of Statistics to understand and respond better to the situation of the poor assumes immense proportions and should not be downplayed by anyone. The elimination of poverty remains a major objective of the global community as reflected in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that are to be achieved by 2030. The promise of the ‘Good Life’ depends on it and Guyana must not lose sight of that objective.

Contradictions

In closing out this discussion on individuals, one should not lose sight also of the fact that the issue of burden shifting goes beyond the working poor. Another group of taxpayers, those in the middle, has been made to increase their share of the burden significantly. Under the old proportional tax system, persons earning between $180,000 and $200,000 would have paid between 17 to 18 per cent of their income in taxes. With the new system, their share of the burden would have risen significantly to 25 per cent. In contrast, persons whose income exceeds $500,000 will see a reduction in their burden from 28 to about 26 per cent of income. This is where tax policy becomes a question of reasonableness and the design of the tax system assumes great importance. Contradictions of the sort facing the workers in the middle drive people to appeal for equity and fairness in the tax policies and the tax system. The final part of this article will address this point and its implications for the business sector.

(To be continued)

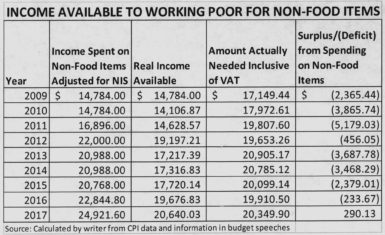

The Lucas Stock Index (LSI) fell 0.40 percent during the second period of trading in December 2016. The stocks of four companies were traded with 32,338 shares changing hands. There were no Climbers and three Tumblers. The stocks of Demerara Bank Limited (DBL) fell 1.39 percent on the sale of 8,710 shares. The stocks of Demerara Distillers Limited (DDL) fell 2.08 on the sale of 23,334 shares while the stocks of Guyana Bank for Trade and Industry (BTI) fell 0.33 percent on the sale of 237 shares. In the meanwhile, the stocks of Republic Bank Limited (RBL) remained unchanged on the sale of 57 shares.