Saturday, 19th August, 1939, start of Test Match # 274, the final Test in the three match series between England and the West Indies. The atmosphere was almost surreal as the silvery barrage balloons cast their ominous shadows across the Kennington Oval, London, with the threat of war looming larger with every passing day.

Conscription had started two days before the cricket season commenced; the front pages of the 2nd of August newspapers had announced evacuation plans for children from major cities, the details of petrol rationing had been posted, air raid shelters were being distributed, and travel was increasingly hard as the forces commandeered the railroad and road networks…

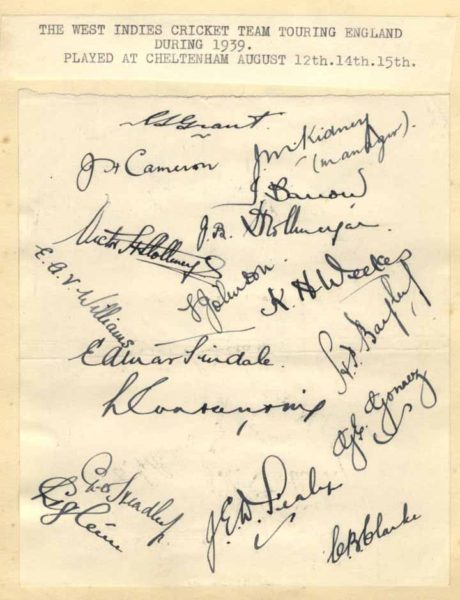

The three day Test concluded in a draw on Tuesday, as 1,216 runs were scored. The hosts battingfirst compiled 352, to which the visitors replied with 395 for 6, by the close of play on Monday. The Stollmeyers ‒ Jeffrey, 59, and Victor, 96 ‒ George Headley, 65, and Ken Weekes, 137, with eighteen 4s, laid the table for Leary Constantine. The cricket magician – Leary could perform virtually any feat with a bat or a ball ‒ must have realized he was playing in his last Test, he would be 38 by the autumnal equinox. Resuming on the final day on 1, he plundered the English attack for a further 78 in an hour, to follow his five wicket haul. His innings included eleven 4s and one six off of Perks into the pavilion.

The 1940 Wisden Cricketers Almanack recorded the occasion as follows, His batting reached a climax of audacious adventure at the Oval Test…Constantine gave the England bowlers such a cracking, like a strong man suddenly gone mad at fielding-practice . The English fielders were scattered around the boundary in a vain attempt to stop the massacre which ended with wicketkeeper Wood running a long way to take a stunning catch off of a ball that had taken flight from the back of the bat. In England’s second innings, Hutton, 165, and Hammond, 138, joined the run feast whilst adding 264 for the third wicket in three hours. It was Hammond’s twenty-second Test century, one more than the Australian Don Bradman. It was the last Test for six Englishmen and eight West Indians.

The arrival of a letter from Kent County Cricket Club on the 24th of August, notifying the tour party that their first class encounter at St Lawrence Ground, Canterbury, from the 30th August to the 1st September might have to be cancelled due to the County’s inability to field an eleven, as players were joining up or being called up to the forces, set off a chain of events…The decision was taken to abandon the tour ‒ the first time ever a Test tour had been aborted ‒ over the objection of some members of the party. The other games forgone were Sussex at Hove, 26th-29th, August; W E Butlin’s XI at Skegness, Lincolnshire, 2nd-3rd September; England XI at Folkstone, 6th-8th, September; H D G Leveson-Gower XI at Scarborough, 9th-12th, September; and two matches versus Ireland, at Dublin and Belfast, (dates unknown)

The West Indies had enjoyed a tour of mixed results. They had lost the Test series 1-0, having collapsed in the second innings in the First Test at Lord’s, and had an overall record of ten wins, six losses, eighteen draws, with two games abandoned. The visitors had been part of the debate of that summer’s experiment, where eight ball overs had been delivered in first class and club cricket.

George Headley had the best aggregate for the summer, 1745 runs, for an average of 72.70 per innings. At Lord’s, he contributed 106 out of 277 in the first innings, and 107 in total of 225 in the second. It was the first time any batsman had ever scored two hundreds in a Test at Lord’s. Headley had previously performed the feat in the Third Test versus England at Bourda, Georgetown in 1930.

The visitors hastily arranged to leave on the first available ship. The team, minus Constantine and Manny Martindale who had homes in England – they were professionals in the Lancashire League – caught the midnight train from Euston Station, the main gateway from London to the West Midlands, the North West, North Wales and parts of Scotland.

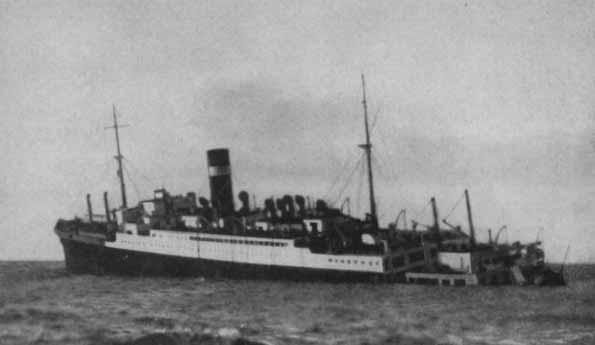

On Saturday, 26th August, the team departed from Greenock on the Clyde, aboard the steamship SS Montrose, of the Canadian Pacific Overseas Service line. Four hundred passengers boarded in Scotland, joining the eight hundred who had embarked at Liverpool, as the liner set off for Quebec and Montreal. The Admiralty recalled the ship two days out from port, but then allowed it to resume its trip six hours later. The next option available had been the liner, the SS Athenia which was scheduled to depart Liverpool on the 1st September.

At 11.15 am on Sunday, 3rd September, 1939, Britain’s Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain broadcast the following statement to the nation on radio:

“This morning the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German Government a Final note stating that, unless we heard from them by 11 o’clock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us.

“I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received, and that consequently this country is at war with Germany.”

Great Britain and France had declared war on Germany following the German invasion of Poland on the 1st of September, 1939.

The West Indies cricketers were now on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, their arrival in Montreal on Saturday, 2nd September having been confirmed by a telegram from T Geddes Grant Co Ltd, in Trinidad, the firm owned by the family of the Captain Rolph Grant. The SS Athenia, the other liner they might have taken was trying to avoid the shipping lanes frequented by the many transatlantic steamships that plied their trade between Europe and North America. The SS Athenia had departed Glasgow on the 1st September, for Montreal, with stops at Liverpool (2nd) and Belfast, without recall. The ship carried 1,101 passengers, mainly women and children, and 315 crew.

Fourteen U-boats had sailed from Germany in mid-August when it appeared that War with the West was imminent. Hitler had issued strict orders that the U-boats were to follow the Prize Rules (Prisenordnung) signed by Germany in 1936. Under these rules of engagement, merchant ships were to be stopped and searched and if found to be carrying contraband, they could be sunk, but only after the crews had been safely evacuated in lifeboats and provisioned for. The ship would be allowed to sail if no contraband was found. Warships or troop ships could be sunk without warning. Attacks against passenger liners were prohibited, unlike in the First World War when the Germans conducted unrestricted submarine warfare, and almost put a stranglehold on the shipping lanes of Britain.

At 12:56 hours Berlin time on the 3rd September, BdU (Commander in Chief of the German submarines in World War II) Karl Dönitz broadcast an urgent encoded message: “Hostilities with England effective immediately”. Two more messages followed, each one an hour apart; attacks on enemy shipping were to commence immediately in accordance with the Prize Rules, and vessels should feel free to begin hostilities without awaiting provocation.

A few hours later at 16:30 hours, the bridge watch on U-30 under the command of Oberleutant Fritz- Julius Lemp spotted a large ship on the distant horizon. The U-boat was at the edge of its northern patrol zone, Grid AM1631, about 250 miles northwest of Ireland and about 60 miles south of Rockall Banks. Lemp set off in pursuit on the surface, then dived for a closer investigation. The ship was blacked out and zigzagging at 15 knots per hour, away from the regular shipping lanes. It must be a British Armed Merchant Cruiser, a converted liner fitted with naval guns, and fair game under the Prize Rules, Lemp concluded.

The Captain of the SS Athenia, James Cook was heeding the warning British Admiralty had issued the week before, to be on a ‘war footing’. Earlier, he had hugged the Irish coastline to avoid the regular deep water shipping lanes which the German U-Boats would find favourable. During the day passengers had performed lifeboat drills, which were left stripped of their covers. Cook ordered the ship’s lights out and porthole curtains drawn over the ones which had been painted out. Passengers and crew were ordered not to smoke on the decks, lest the lights from matches or cigarettes be seen.

At 19:40 hours, after having shadowed the ship for three hours, from a submerged position Lemp ordered the firing of the first torpedo; the first shot in the Battle of the Atlantic had been fired. It was not a warning shot across the bow! It struck the ship’s engine room on the port side, ripping open the bulkhead between the boiler room and the engine room, and destroying the access stairs to the upper decks from the third class and tourist dining rooms. The stricken ship stopped in its tracks, and began to settle by its stern. A second torpedo was fired, it malfunctioned and careened off course. Lemp feared the torpedo might circle back and strike the U-boat, and immediately ordered a deep dive. The U-Boat resurfaced in twilight, and Lemp examined the results of his action with a pair of binoculars. The liner did not appear to be sinking, so he issued instructions to fire a third torpedo, which also malfunctioned. Survivor reports claimed that the ship suffered another hit on the main mast, missing the radio room which suggested that the deck gun of the U-Boat was also fired, but this was never confirmed.

Concealing his approach Lemp crept closer to the prey until he was able to make out the name on the side. A review of the boat’s copy of Lloyd’s Register revealed the identity of the darkened steamship.

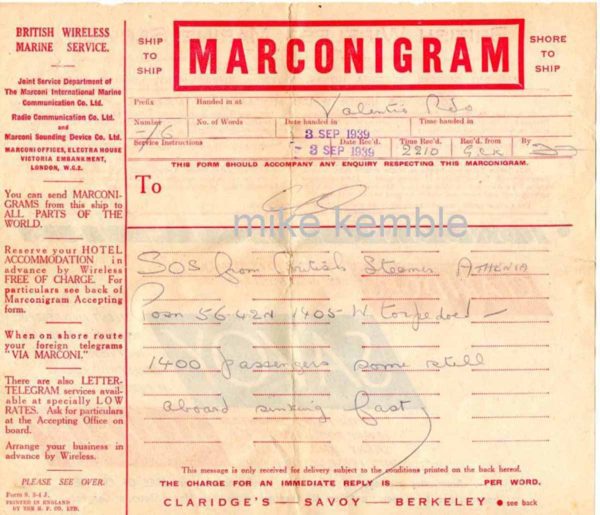

Oberleunant Lemp, Commander of U-Boat 30 had just torpedoed the SS Athenia, a Briitsh passenger liner of the Donaldson Atlantic line. The magnitude of his blunder was immediately apparent to the crew, they had sunk an unarmed passenger vessel. A few minutes later, the radio operator of the listing ship sent out a distress signal in plain English, giving the ship’s identity and position, along with the three letter code SSS, the indicator that the attack had come from a submarine. Lemp did not render assistance to his victims or report the incident to BdU, instead he disappeared silently in the darkness and later swore his crew to secrecy over the incident.

The sea was calm and the weather was good, and the ship remained afloat for more than fourteen hours. Several ships responded to the tragedy: Knute Nelson, a Norwegian merchant ship, Southern Cross, a Swedish yacht, City of Flint, an American cargo ship, three British warships HMS Escort, HMS Electra and HMS Fame. The German liner SS Bremen en route to Murmansk from New York, chose to ignore the distress signal. Miraculously only 112 lives were lost, including 19 crew. Several lives were lost during the rescue operation, including an entire lifeboat of survivors when their boat was chewed up by the propeller of the Knute Nelson. At 10:40 hours, on the 4th September, 1939, the SS Athenia rose vertically and then sank into the depths of the North Atlantic.

The attack drew condemnation from all over the English-speaking world. The British were livid, the Germans had broken all the rules of engagement and viewed it as a return to the barbarism of the First World War. An immediate consequence was the introduction of the convoy system for the movement of ships. American President Roosevelt refused to be drawn into the war despite the loss of 28 American lives.

The German reaction

Dönitz first learnt of the tragedy from the BBC, and as Lemp had not reported in, Berlin was still in the dark. Upon reviewing the assigned patrol zones in the Atlantic, Dönitz concluded that U-Boat 30 had been responsible for the sinking.

The Führer was furious, and accused Britain of sinking the ship to lure the USA into the war. Years of effort to erase the world’s memory of the unrestricted submarine warfare of World War I had been wiped out in a flash in the first few hours of declared hostilities. The Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebels was ordered to broadcast that no U-Boats had been in the area at the time of the incident, and that the SS Athenia had been sunk by a British submarine or mine. On October 23rd, the Völkischer Beobachter, the official Nazi newspaper published an article accusing the First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, of sinking the SS Athenia to turn other countries against Nazi Germany.

Oberleutant Lemp maintained radio silence until the 14th September when he requested permission to drop off Adolf Schmidt for urgent medical attention in neutral Iceland, following an encounter with two British warships after sinking the British freighter Fanad Head. When U-Boat 30 limped into port on the 27th September, 1939, Lemp had sunk another ship, the SS Blairlogie. He had had shown remarkable courage and leadership under a punishing depth charge attack, and brought his boat home despite severe battle damage.

Lemp expected to be relieved of his command or to face a court martial, and admitted to Dönitz he had sunk the SS Athenia in error. Dönitz then sent Lemp to Berlin to Grand Admiral Erich Räder, Head of the Kriegsmarine (Nazi Navy) from 1939 to 1943. After the debriefing, Räder reported to the Führer who decided for political reasons that the incident should be kept secret. This massive cover up was only unveiled by Räder during the Nuremburg Trials in 1946.

Räder took into account Lemp’s performance, opted against a court martial and ordered Lemp to alter the Kriegstagebuch (U-Boat log book ), and two pages were clumsily replaced; the detailed originals were swopped for false reports indicating that U-30 was 200 miles west of the incident at the time. At Nuremburg, Räder claimed not to have never seen the Völkischer Beobachter article.

Adolf Schmidt who had become a POW in 1940, had kept silent about the incident despite several interrogations. Schmidt had been sworn to secrecy by Lemp in privacy, felt the oath ended with the war and provided testimony at Nuremburg about the incident. He had been one of the few seamen to go on deck and witness the tragedy.

And the West Indians?

On the 4th September, 1939, at the Westmount Athletic Ground, the West Indies played a Montreal XI. The hosts batting first were dismissed for 35. The visitors responded with 207 for 8. Montreal were 64 for 5 when stumps were drawn.

A second match scheduled for the next day was cancelled.

The Stollmeyers, Grant and Gerry Gomez remained in Canada, whilst the rest of the tour party travelled to New York by train, where the Jamaicans, Les Hylton and John Cameron departed. Manager Jack Kidney, Bertie Clarke, Derrick Sealy and Foffie Williams arrived in Barbados on the 13th September, aboard the SS Argentina. Tyrell Johnson sailed on to Trinidad the next day whilst Peter Bayley, the lone cricketer from British Guiana spent a week in Barbados before heading home. The Jamaican trio of Headley, Weekes and Ivan Barrow arrived in Kingston, from New York on the SS Antigua on the 24th September.

Test Match #275 was played on the 29th and 30th March, 1946, with New Zealand hosting Australia, in Wellington. It was scheduled for two three days but…

The next West Indies Test Tour was to India in 1948. The team assembled in London, after travelling by various boats to England. On the 16th October, the team boarded an Air India flight at Heathrow Airport, London and arrived in Bombay at 630 am on the 17th October.

Only Headley, Gomez and Jeffrey Stollmeyer remained from the 1939 team.

Oberleutant Fritz-Julius Lemp returned to U-Boat command. He was killed in action on the 9th May, 1941, in the North Atlantic east of Cape Farewell, Greenland. He had ordered his crew to abandon the badly damaged boat when he thought it was going to be rammed by a British destroyer. The ship diverted at the last minute, and the English crew was able to board and take command of U-Boat 110.

It was one of the most important captures of World War II, and one of the best kept secrets of the war. A crew from HMS Bulldog boarded the abandoned vessel and retrieved a Naval Enigma machine with the rotors set, ciphers and the current code books. The U-Boat was sunk to disguise the find and everyone involved in the event was sworn to secrecy.

Alan Turing and the codebreakers at Bletchley Park were able to crack the German Naval Enigma code with this snare. The course of the war in the Atlantic was changed.

Test cricket returned…