BELFAST, (Reuters) – After a decade of bitter compromises over paramilitaries and policing, Northern Ireland’s power-sharing government finally fell apart this week over the abuse by farmers of a green-energy grant to burn fuels such as wood pellets instead of coal.

The confrontation has exposed a growing rupture in trust between Catholic Irish nationalists and pro-British Protestant unionists whose cooperation underpins the 1998 Good Friday peace agreement that ended three decades of bloodshed.

While there is no sign of a return to violence that killed 3,600 people, the political crisis looks set to paralyse government in the province for months at the same time as Britain’s exit from the European Union threatens simultaneous shockwaves to its economy and constitutional status.

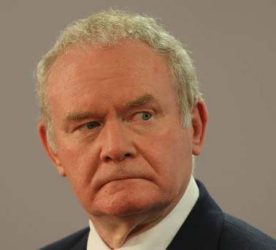

“I’m not sure that power-sharing can be restored now,” Jeffrey Donaldson, a senior member of the ruling pro-British Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) told Irish state radio RTE yesterday, a day after Irish nationalist, and ex-Irish Republican Army (IRA) commander, Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness, resigned over the affair.

“I really don’t think that Martin and his colleagues have begun to contemplate the damage the decision they made yesterday has done to the prospect of power sharing in the future.”

The Good Friday Agreement, negotiated by former U.S. senator George Mitchell and ratified in May 1998, effectively ended the “Troubles” that had torn apart Northern Ireland and was based on a power-sharing pact to govern by cross-community consent.

McGuinness’s resignation means a snap election is more than likely, bringing the power-sharing government to the brink of collapse. McGuinness raised the prospect of a lengthy renegotiation of any power-sharing, saying there would be “no return to the status quo” after an election.

There has been a decade of power-sharing between Sinn Fein, once the political arm of the IRA, and the DUP which have overcome fierce disagreements over rival marches, the legacy of the Troubles and constitutional issues.

The green energy scandal proved to be the final tipping point.

For months Northern Irish media have revelled in stories of farmers heating barns night and day to burn as many wood pellets as they and other business owners could to take advantage of a subsidy that gave them 1.60 pounds for every 1 pound spent.

Unlike a similar scheme elsewhere in the United Kingdom legislation lacked a cap and could cost taxpayers up to 490 million pounds ($595 million), almost 5 percent of the region’s annual budget.

First Minister Arlene Foster, who launched the scheme four years ago, apologised, but insisted her party closed it as soon as flaws became apparent.

While her refusal to resign was the trigger for the first collapse of the government since McGuinness agreed to share power with rivals a decade ago, all sides admit that the political fissures go much deeper.

“The heating scandal is the occasion for the resignation, it’s not the cause,” said Brian Feeney, a columnist for Irish nationalist newspaper the Irish News.

“They have a long list of grievances and they have just decided it’s not going to go on any longer.”

While the power-sharing deal calls for a partnership of equals, Sinn Fein says the DUP has been treating it with “provocation, arrogance and disrespect” culminating, they say, in the scrapping of a 50,000-pound grant for disadvantaged children to learn the Irish language just days before Christmas.

“Sinn Fein will not tolerate the arrogance of Arlene Foster and the DUP. We now need an election to allow the people to make their own judgment,” McGuinness said after his resignation.

An election is the “highly likely” next step, the British government’s Secretary of State for Northern Ireland James Brokenshire said on Tuesday, unless Sinn Fein agrees to appoint a replacement for McGuinness within seven days, something it has said it will not do. McGuinness recently took a break from some of his duties because of an undisclosed illness.

But an election appears likely to just mark the starting gun for a renegotiation of the terms under which the two parties share power.

Sinn Fein members in recent days have begun to hint at demands likely to be made including funding additional rights for Irish speakers and the lesbian and gay community, which the DUP has blocked and for inquiries into deaths in the “Troubles”.

Failure in those talks could cause devolved powers to revert to London and open the possibility of a deeper rethinking of the concept of power sharing.

The collapse of the relationship between McGuinness and Foster also risks paralysing the region’s response to Britain’s planned exit from the European Union as London prepares to trigger divorce talks.

Sinn Fein, which campaigned for Britain to stay in the European Union, says Foster has failed to properly represent the 56 percent of Northern Ireland voters who voted “Remain”.

Foster, who campaigned to quit the EU, said she must instead respect the opinion of the 52 percent of voters in all of the United Kingdom who wanted to leave.

“Brexit is a complete mess and everyone here seems to be ignoring it,” said Ollie Woodhouse, a 21-year-old bar-tender walking through central Belfast yesterday. “It is definitely time for change in Northern Ireland.”