Following last week’s discussion of Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWF) as a mechanism for avoiding and/or controlling the triad of crises typically associated with booms in oil and gas export revenues, I describe below the Government of Guyana’s declared intention with regards to its own SWF.

Following last week’s discussion of Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWF) as a mechanism for avoiding and/or controlling the triad of crises typically associated with booms in oil and gas export revenues, I describe below the Government of Guyana’s declared intention with regards to its own SWF.

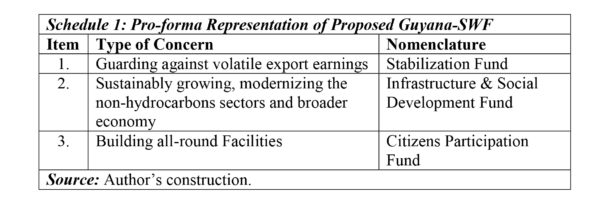

Recently, the Ministry of Natural Resources has declared Guyana’s SWF is intended to: 1) “protect the economy from the volatile nature of natural resource revenue”; 2) “grow and modernize the sustainable non-extractive sector of the economy; and 3) “enhance the capacity of our people”. Towards these ends three sub-funds have been proposed, namely, a Stabilization Fund; an Infrastructure and Social Development Fund; and, a Citizens Participation Fund. Additionally, the ministry has declared: “hydrocarbon development, and by extension all other extractive industries, can be catalysts for a green economy.”

Two technical matters: fiscal space and the Dutch Disease are central to a fuller understanding of the dynamic interplay between an oil and gas export boom and growth/development in small poor open economies like Guyana. These are respectively addressed below.

Fiscal space

As stated last week, in Guyana-type economies fiscal space refers to a boom in export revenues that gives room in the national budget for governments to spend without jeopardizing fiscal and monetary stability. Specifically, increased public spending that does not generate monetary/fiscal gaps is possible only if it 1) is fully financed by taxation; 2) is covered by external grants; 3) is at the expense of lower priority government spending; 4) can be borrowed by government from the banking system without negative consequences for macroeconomic balances.

Dutch Disease

As similarly indicated last week, economists define Dutch Disease (also known as the ‘curse of plenty’) as a function of four sequential outcomes: first, rising wages and prices in sectors other than the booming natural resources sector (oil and gas); second, consequential declines in these sectors’ productivity; thirdly, an appreciation of the exchange rate; and finally, price increases in the other sectors, which further reduce their competitiveness.

Usually, Guyana-type economies would possess weak linkages between their booming oil and gas sectors and others, together with low absorption capacity in their economies. This weakness, compounds the difficulties, resulting in de-industrialization and de-agriculturalisation of their economies.

This sequence, has been diagnosed as the causal link in Guyana-type economies, between their expanding oil and gas sectors and declines in other sectors, especially industry and agriculture. When interpreting, this causal link, oil and gas can be readily substituted for 1) any other commodity export, 2) massive inflows of foreign direct investment, and 3) foreign aid.

The term Dutch Disease was coined as a description of this sequence in the Dutch economy in the 1960s and 1970s (following its natural gas ‘find’). Economists admit that economic policy can sever this causal link, if the authorities 1) control/ sterilize the transmission of increased export revenues into the domestic economy; and 2) prevent the loss of competitiveness in other non-booming sectors, by improving their absorptive capacity. It is essential though, to recognize that expanding oil and gas revenues in such circumstances are usually both volatile and uncertain, reflecting the stark realities of the global hydrocarbons market.

Onshore or offshore?

In introducing SWFs (January 1) I had described them, in part, as “a long-term state-owned pool of money, invested in a variety of real and financial assets, which are held globally”. Several readers have enquired whether this fund or pool of money can be held in local assets (onshore) rather than globally (offshore). My response is that, in theory, the fund can be held either onshore or offshore or a combination of both.

There are, though, enormous risks attached to investing part or all of these foreign currency earnings in domestic assets of economies like Guyana. If the fund holdings are kept in domestic assets (onshore), there is a grave danger of these holdings leaking into the domestic money supply and the national budget. This would threaten financial stability due to, (but not limited to), likely changes in domestic prices (inflation) and the exchange rate, as well as the behaviour of economic agents (consumers and investors).

HSF

It may be useful at this stage to draw attention to Trinidad and Tobago’s Heritage and Stabilisation Fund (HSF). Having the largest Caricom oil and natural gas sector, the government had established the HSF in 2007, as a replacement for its Interim Revenue Stabilisation Fund. The HSF is designed to 1) stabilize government revenue in the event of crude oil or natural gas price deviations away from that used in preparation of their National Budget; and 2) save some of the energy wealth for future generations. The HSF operates through rules which indicate how its funds should be accumulated, held, and drawn-down.

Currently, as noted in my January 1, column, HSF holdings had equalled US$5.5 billion in late 2016. This is a tiny amount (compared to the holdings of the Top 5 SWFs). However, the HSF is ranked 8 out of 10, in the Linsburg/Moduell Index of Transparency. And, in 2011 the HSF was hailed as the world’s best performing SWF, with a 9 per cent per annum return. Nevertheless, the HSF has suffered from strong criticism by civil society and other groups in Trinidad and Tobago.

Conclusion

Based on my evaluation of reports/research on this topic, I shall seek to identify major lessons which Guyana might draw on, as it approaches the design of its own SWF and the political economy analysis of its impending oil and natural gas production and export.