Dear Editor,

After a relatively calm decade, the Guyanese banking system is suffering under Minister Winston Jordan. One of the main drivers of this decay is the conspicuous lowering of the confidence levels of the private sector in the economic management of the affairs of the state by Mr Jordan. One way this can be represented is in the rise of non-performing loans (NPLs) in the financial sector.

I have said before and I am saying it again: Carl Greenidge would have been a much more reassuring pair of hands for Guyana at the Ministry of Finance. The current office holder, with three successive budgets, has not once but twice proven to be one big amusing entertainer who does not have the awareness of the needs of the economy to be able to deliver the required policy actions to get Guyana back on track. What is clear is that he just cannot comprehend the real needs of the people and bring common sense to the economic problems of the nation.

What really matters today is not how much bad economic news you can report on in your budget speech, but what concrete actions you are capable of taking to stabilize the economy. But we all recognize that economic strategy is not Mr Jordan’s forte. This mentality of taxing a flat economic cake, frustrating the productive sectors and spending recklessly on projects like the D’Urban Park parade ground is clearly an intellectually bankrupt economic strategy. His saving grace is hoping for oil before 2020. But that is exactly that ‘hope’, because oil will not flow until 2021-22 at the earliest based on information I saw.

What really matters today is not how much bad economic news you can report on in your budget speech, but what concrete actions you are capable of taking to stabilize the economy. But we all recognize that economic strategy is not Mr Jordan’s forte. This mentality of taxing a flat economic cake, frustrating the productive sectors and spending recklessly on projects like the D’Urban Park parade ground is clearly an intellectually bankrupt economic strategy. His saving grace is hoping for oil before 2020. But that is exactly that ‘hope’, because oil will not flow until 2021-22 at the earliest based on information I saw.

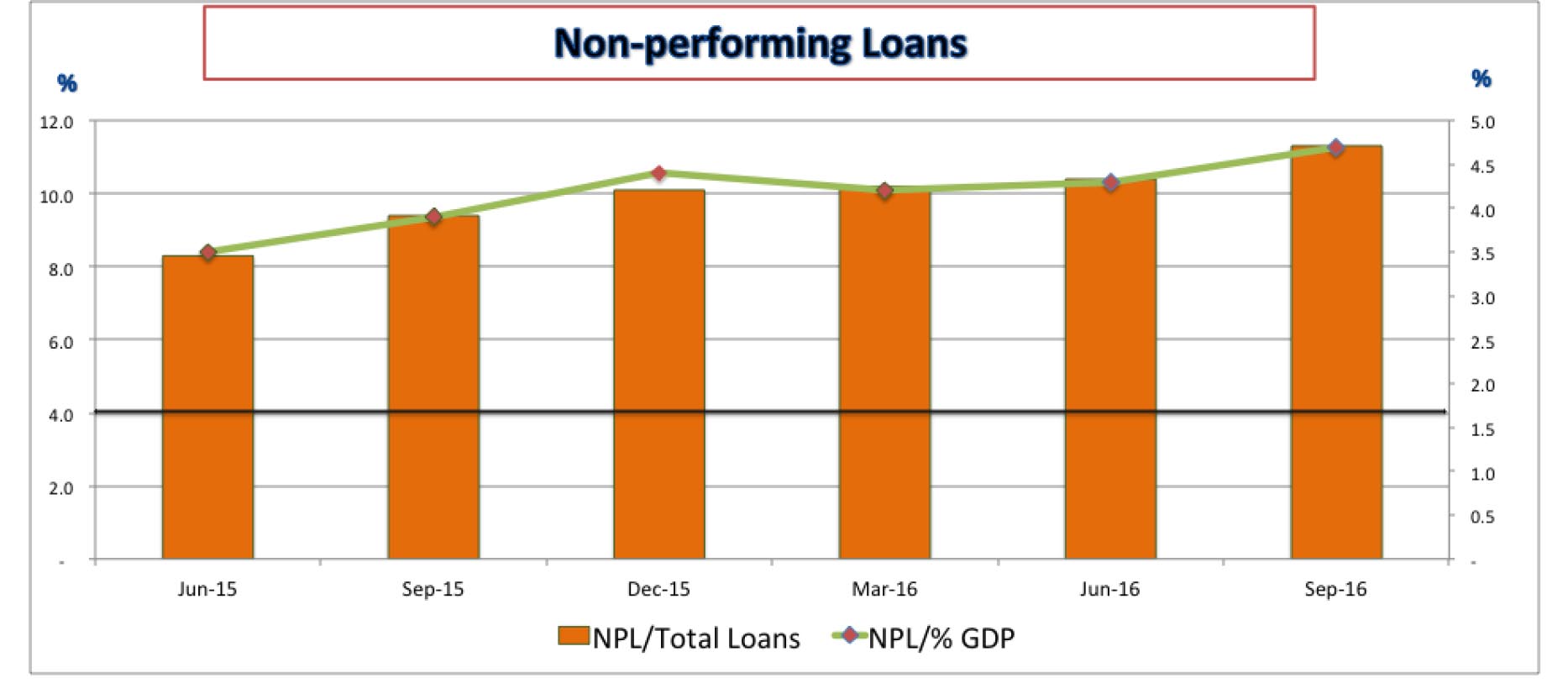

Let me put some facts on the table to back up why I believe that there is an unprecedented decay happening in the banking sector. Asset quality is an essential part of sound banking, and one of the main indicators of its quality is the ratio of non-performing loans (bad debt) to total loans in the system. As the graph below illustrates, the Guyana rate of loans going bad is almost three times higher than the world’s average of 4% of total loan portfolio. What is even worse is that the bad loans have multiplied by some 36% since the Granger administration came to power. In simple language the size of the bad debt portfolio is clearly going in the wrong direction.

The source of the data in this graph (at top right) is the Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Guyana. NPLs (or bad debt) in the banking sector have moved from 8.3% of all loans in June 2015, at the end of the PPP term, to 11.3% in September 2016. I was reliably advised that at the end of 2016, the rate of bad debt is now some 11.5% of the total loan portfolio. This data clearly indicates the predictable adverse economic trajectory.

The rise of NPLs (bad debts) is a salient feature of a financial crisis. The concern is that persistently high NPLs lock in sluggishness in the economy. For the banks, delays in debt repayment make obtaining further credit more difficult, which often leads to a second round of debt default and even more bankruptcy in companies, especially small businesses.

Any sensible banking leader plagued with a high stock of NPLs is likely to focus on internal consolidation and improving asset quality rather than providing new credit. Because a functional enforcement mechanism at the Bank of Guyana, a high NPL ratio means all the banks will have to do greater loan provisions, which reduces capital resources available for lending, and dents the profitability of the sector. This will drive an even further slowdown of economic growth, which in the end comes full circle to the ordinary man and woman. The graph above proves this fact by illustrating how bad loans as a percentage of GDP have deteriorated by some 35% under the Granger administration since June 2015. At the end of 2016, I am reliably advised that the bad debt as a percentage of GDP was almost 5%. That immediately creates a real but permanent leakage from the economy. Can we afford this?

Any serious government would have done some strategizing around this issue from day one, but it is now clear that the life of ordinary people has little meaning for the ruling elite in the Granger government. From their public actions, they have reduced the most complex issues into sweeping political generalities. Regular people are suffering because of the intellectual deficit in the Granger administration. But do they care?

Yours faithfully,

Sase Singh