Today’s column attempts to draw lessons from global experiences with Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs), operating in the oil and natural gas sector. This effort is intended to aid my ongoing examination of Guyana’s impending development of a robust oil and natural gas sector. Today, such SWFs constitute an important subset of SWFs found in the natural resources sector; with the natural resources sector’s SWFs, in turn, comprising one element in a wide variety of SWFs. The lessons are presented below in no intended order of ranking.

Today’s column attempts to draw lessons from global experiences with Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs), operating in the oil and natural gas sector. This effort is intended to aid my ongoing examination of Guyana’s impending development of a robust oil and natural gas sector. Today, such SWFs constitute an important subset of SWFs found in the natural resources sector; with the natural resources sector’s SWFs, in turn, comprising one element in a wide variety of SWFs. The lessons are presented below in no intended order of ranking.

While as indicated last week, SWFs are multi-dimensional in character, in my view the hydrocarbons-based SWFs can be reduced to two essential dimensions. One dimension refers to economic matters, or more explicitly, the interplay between booming oil and natural gas export revenues and the functioning of the economy. And the other refers to design matters, or the rules governing the operations of SWFs. It is important to note that, in both these dimensions, there are enormous variations.

There is the further consideration that, unlike other countries with established SWFs prior to their hydrocarbons discoveries, Guyana has had no such previous experience; even though for decades, its extractive natural resources sector has accounted for the bulk of GDP, employment and export earnings.

Lesson 1

The first lesson global experiences teaches Guyana is that its SWF should be designed with two basic factors in mind, namely 1) avoiding/controlling inevitable threats and risks which rapid expansion of oil and gas exports pose; and 2) in so doing, seeking to propel the economy along a path that efficiently seizes development opportunities as they arise.

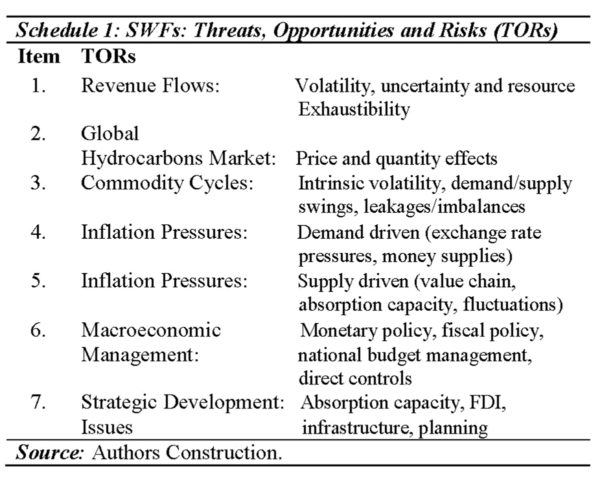

In these circumstances, five risks/threats typically appear along with two opportunities, which could be seized. One risk is the disruption effects of volatile and uncertain revenue flows. These disruptions are often compounded by the time-horizon the country faces, given its resource depletion/exhaustion rate. Such risks are observed in the global hydrocarbons market, where price and quantity effects are manifest; and discernible, in the form of repeated oil and natural gas ‘commodity cycles’.

Experiences show that such occurrences create inflationary pressures on both the demand (expenditure) and supply (cost) sides of the market. Prudent macroeconomic management offers scope for containing these threats/risks, particularly through the mechanisms of sensible national budget management. These mechanisms, however, require strategic focus on situating development priorities correctly. Here experience again suggests that focus on 1) the absorption capacity of the non-oil sectors; 2) the facilitation of synergetic foreign direct investment, (through institutional and policy changes); 3) the build-up of infrastructure; and 4) careful development planning and policy formulation are all central to the country’s ability to convert threats/risks into opportunities.

Schedule 1 summarizes these ideas for the convenience of readers.

Lesson 2

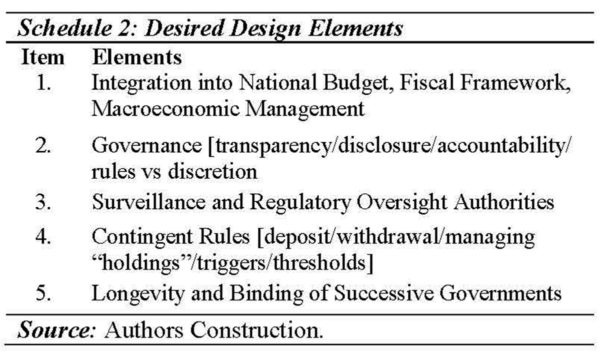

The second lesson follows logically from the first. That is, despite global variations in the design elements of SWFs, there are at least five elements common to successful SWFs. One such element is that SWFs seem to operate successfully only when they are systematically integrated into national budgetary processes and the wider fiscal framework.

Another element is that the template for governance of SWFs should meet established best-practices (as regards transparency, disclosure, accountability, with a bias towards rules-based, rather than discretionary-based procedures). Ensuring this outcome requires that the design of SWFs is unambiguous about the status of the regulatory/oversight/surveillance authority(ies).

Experiences also show that successful SWFs are transparent about the contingent rules governing how funds are deposited, withdrawn, and managed. They also have precise quantitative triggers and thresholds undergirding management’s activities. Finally, one element which seems to stand out above all, is that SWFs should be established as long-term commitments, capable of binding successive governments. More will be said about this element in later presentations.

Schedule 2, summarizes these observations for the convenience of readers.

Lesson 3

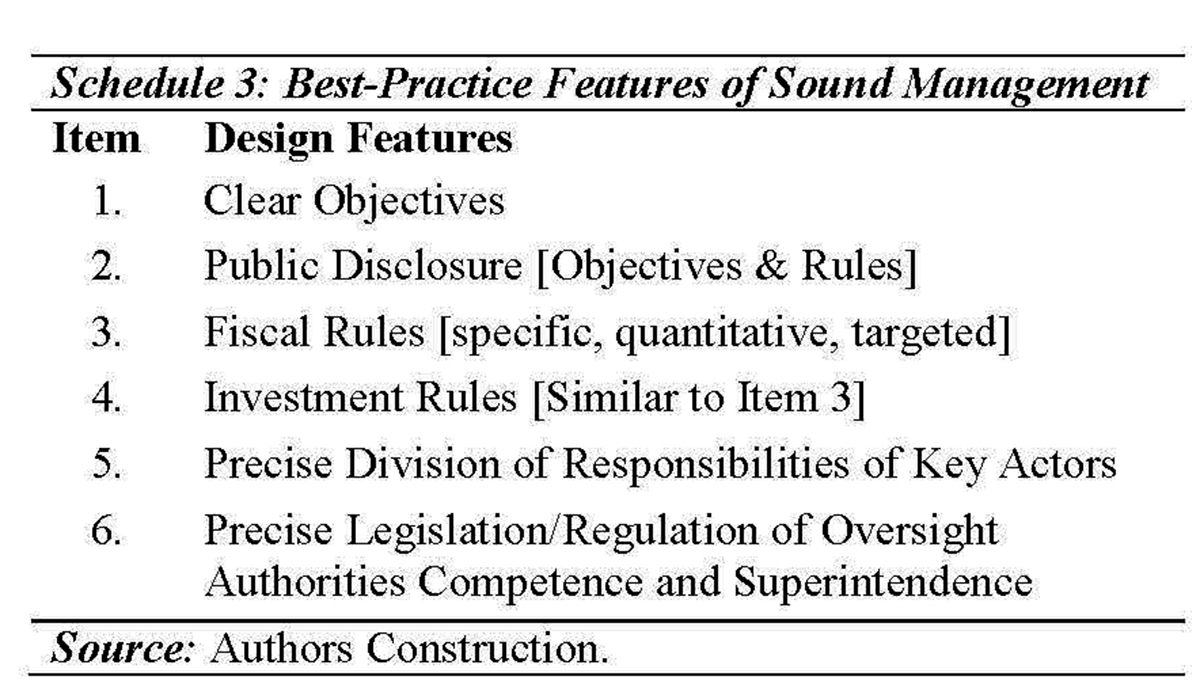

Based on reported performances of well-managed SWFs, certain best-practices have been identified. These include 1) a clear and precise statement of the national objectives, which the SWF is pursuing ; 2) public disclosure of these objectives along with the accompanying rules for securing their attainment; 3) typically, such rules should specifically identify the fiscal regulations/targets which apply for any additions to, or transfers from, the SWF, (as well as the investment rules). Here again, best practices suggest that SWFs should state precisely as well, the division of responsibilities for key actors, as well as equally precise legislation/regulation of their areas of competence and superintendence, in the established oversight and regulatory system.

For readers’ convenience the features of this lesson are summarized in Schedule 3.

Conclusion

Next week I shall continue this discussion, with additional lessons. I shall have more to say about two of the most troubling aspects of SWF operations, namely, determination of their national objectives and, the rules that derive from economic analysis of oil and gas ‘booms and busts’ in Guyana-type economies.