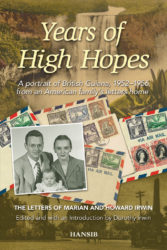

By Dorothy Irwin

Review by Donald Trotman

(737 pp Published by Hansib Publications Limited)

Just when the traditions of keeping personal diaries and of writing substantial personal letters have almost fallen into desuetude, here comes a book that loudly invites their revival, while at the same time straddling two eras and two continents.

Years of High Hopes encompasses the genres of both traditions – letter writing and diary keeping. In fact, it may even be called a reconstituted letter-diary, comprising nearly two hundred letters written in daily doses, some large, some small, but all uniquely flavoured with special story-telling quality, which the author’s parents, Marian and Howard Irwin, generate in their recording of daily events through the medium of letters.

Years of High Hopes encompasses the genres of both traditions – letter writing and diary keeping. In fact, it may even be called a reconstituted letter-diary, comprising nearly two hundred letters written in daily doses, some large, some small, but all uniquely flavoured with special story-telling quality, which the author’s parents, Marian and Howard Irwin, generate in their recording of daily events through the medium of letters.

While due credit must be given to Dorothy Irwin, the author of this book, it is submitted, with respect, that her mother Marian, should be credited with being the real author of it and that Dorothy be urged to accept her own part as co-author or glossator. For it is Marian’s remarkable written expressions that have made the book possible. Her peculiar gift of communicating ordinary, everyday events into grippingly dramatic prose, makes the book so sustainably interesting.

A wide and general description of the book tells the story of the life of a young American couple, Marian and her husband Howard, and their two infant daughters, Elizabeth and Dorothy, during the period 1952 to 1956, in what was then British Guiana; and the variety of their experiences and encounters during those years.

But that variety is so considerable, almost infinite, that it could do with some measure of classified arrangement that inures to the enhancement of it; and adds spice to the enjoyment of its readers; and the author has succeeded in doing this with an orderly and methodical collocation of its contents.

Consequently, the composite letter-diary of Marian and Howard together with Dorothy’s Prologue and Epilogue, may be divided into four conveniently understandable categories – Autobiography, Biography, Social and Political, History.

The letters relate the personal life experiences of the couple. Both educated college graduates and of apparently wealthy American families, they came to live in an underdeveloped tropical country where the amenities for comfortable living were not as available as what they were accustomed to; and a country which still suffered from the vicarious consequences of a ravaging war that had devastated the social and economic life of its governing imperial master, Britain.

Allowing Howard to pursue his biology teaching at the prestigious Queen’s College for boys and his outreach botanical researches in preparation for his future academic career, Marian was content to stay at home. She settled down to efficient housekeeping and household management, dutifully ensuring that Howard was well fed and tidily clothed, and devoting much of her time to the loving care and attention of their infant daughter Elizabeth, and later to the newborn Dorothy, while finding time to write her almost daily letters to her and Howard’s family in America.

These letters were consistently graphic and detailed, extending to events outside of the home, capturing the feeling and spirit of the Guianese people and objectively observing the social, political and economic conditions of the country.

What comes out of Marian’s letters are the vivid expressions of a courageous woman of strong character, determined to meet and beat the challenges of living in a strange country whose citizens were still walking waywardly in the footsteps of their forefathers, trying to find paths that would eventually lead them out of the labyrinth which had been systematically built by their colonial masters over many years of slavery, indenture, malign oppression and benign neglect. Marian insulated herself from the negative influences of these phenomena by consciously managing to avoid assimilating them. She wrote them away, stayed home for much of the time, cooked, washed, baked and sewed; she related only to a small circle of friends and engaged in few social activities.

As the days and years went by, Marian’s letters continued to be detailed and descriptive, whether they dealt with purely domestic matters or with extra-marital happenings. But her discipline of taking time to sit down and write in the midst of all her household chores and constraints was remarkably consistent. Her creative energies were not exhausted by these mundane preoccupations.

Howard took second place in the actual letter-writing exercise, but when he occasionally put his thoughts to paper to his own parents or to Marian’s, they could compete commensurately with hers. However, his ‘storkgram’ of October 11, 1955, sent to his in-laws informing of the birth of Dorothy (the author), is an exemplary lesson in literary brevity. It reads “Girl born 10th 9lbs 6oz blonde 21 in both doing well”

His letter of July 11, 1953 to Tom at pages 339 to 342 of the book was full of news of his work at school and in travels connected with his botanical researches in the wilds and interesting persons and places encountered during these outreaches. Similarly, one of April 21, 1956 to Marian while he was still in British Guiana and she had gone back with the children to the USA as his job had come to an end, went on about his own solitary existence.

But it is to Marian that we have to keep returning when the vitality of narrative has to be sustained. It is to her that we look for a searching account of the nuances, attitudes and mannerisms of Georgetown’s middle-class society, more particularly the genteel ladies of the city’s superficial social and cultural elite. It is from Marian that we get a bird’s eye view of the political and economic landscape of British Guiana in the 1950s.

It might very well be that Marian’s assessed observation of the economic conditions was more relative than real, having regard to the fact that she had come from a well-provided family household. Her comparison of comfort and convenience between life in America and life in British Guiana may have led her to making unfair assumptions which prevented her from accepting things as they were in her new host habitat, from wanting too many things as she used to have back home and from adjusting to a different economic environment of lesser sufficiency, though not unbearably unlivable.

Her reporting of the political situation in the colony was more realistic, giving an unvarnished sketch of the country’s political climate and leading political and official characters in the early days of its grant of independence, the greedy withdrawal of that grant, the revocation of the 1953 independence constitution and the retrograde return to imposition of direct rule by the United Kingdom government.

Despite the wide-ranging variety of persons, places and experiences displayed in the pages of Years of High Hopes, the focal part of the book is the Queen’s College Compound where Howard taught biology and which Marian saw as an extension of her life and his.

It commanded centre stage in the dramatic portrayal of the lives of the College’s masters, their wives and of the students and student activities. Details of many of these real-life performances are so enjoyably scripted in Marian’s letters, that they must be left to be relished by avid readers rather than be made to suffer from inadequate rendering by the writer of this review.

The author’s experience and expertise acquired in her career in the publishing industry in her country of domicile, the USA, have enabled her to compose the collection of letters which comprise the book, in a way that makes it seem as though she were living through and in those lettered experiences of her parents in the country of her birth, and spiritually bonding with them and with it.

The nostalgic Epilogue of Years of High Hopes, recollects her return to Guyana in 1994 with her father Howard and evidences a psychical connection by the author with a place she could not have recognized from memory, since she was only five months old when she was last there. But which her emotional intelligence let her know that it was and will continue to be a part of her and a place to which she belongs, wherever else she may happen to be, and however long she may happen to live.