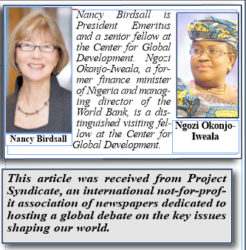

By Nancy Birdsall and Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala

By Nancy Birdsall and Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala

LAGOS – The countries of Sub-Saharan Africa have reached a critical juncture. Strained by a collapse in commodity prices and China’s economic slowdown, the region’s growth slipped to 3.4% in 2015 – nearly 50% lower than the average rate over the previous 15 years. The estimated growth rate for 2016 is lower than the population growth rate of about 2%, implying a per capita contraction in GDP.

Sustained economic growth is essential to maintain progress on reducing poverty, infant mortality, disease, and malnutrition. It is also the only way to create sufficient good jobs for Africa’s burgeoning youth population – the fastest growing in the world. As Gerd Müller, Germany’s development minister, noted at a recent press conference, “If the youth of Africa can’t find work or a future in their own countries, it won’t be hundreds of thousands, but millions that make their way to Europe.”

One way to sustain growth and create jobs would be to collaborate on planning and implementing a massive increase in infrastructure investment across Africa. Public infrastructure is particularly important. This includes highways, bridges, and railways linking rural producers in landlocked countries to Africa’s urban consumers and external markets; mass transit and Internet infrastructure to accommodate greater commercial activity; and electricity transmission lines integrating privately financed power plants and grids.

Major regional projects are also needed to knit together Sub-Saharan Africa’s many tiny economies. This is the only way to create the economies of scale needed to increase the export potential of African agriculture and industry, as well as to reduce domestic prices of food and manufactured goods.

While governments in Africa are spending more on public infrastructure themselves, outside finance is still required, especially for regional projects, which are rarely a top priority for national governments. Yet aid from Africa’s traditionally generous foreign donors, including the United States and Europe, is now set to shrink, owing to political and economic constraints.

But there may be a solution that helps Africa recover its growth in a way that Western leaders and their constituents find acceptable. We call it the “Big Bbond” – a strategy for leveraging foreign aid funds in international capital markets to generate financing for massive infrastructure investment.

Specifically, donors would borrow against future aid flows in capital markets. That way, they could exploit current low interest rates at home, as they generate new resources. With 30-year US Treasury rates of about 3%, donors would have to securitize only about $5 billion to raise $100 billion. That money could come from the $35 billion in annual official development assistance (ODA) to Africa (which totals about $50 billion) that takes the form of pure grants.

Donors would pass on the interest cost to African countries, reducing their own fiscal costs. For African countries, the terms would be better than those provided by Eurobonds. In fact, as audacious as it may sound, passing on the interest costs to recipient countries could actually bolster their debt sustainability.

According to a study of eight countries by the African Development Bank’s Policy Innovation Lab, a 3% interest rate in US dollar terms would be lower than the marginal cost of commercial borrowings undertaken by several African countries over the last five years. Moreover, far longer maturities and grace periods, compared to market finance, would ease growing pressure on foreign-exchange reserves.

Frontloading aid in this way is not new. Doing so in the early 2000s to finance vaccines saved millions of lives in the developing world. Big Bond resources, managed by the African Development Bank, could be used to help guarantee financing for major regional infrastructure projects that have long been stuck on the back burner, such as the East Africa Railway connecting Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi, and a highway stretching from Nigeria to Côte d’Ivoire. Such projects could also be co-financed by private investors.

Moreover, the Big Bond could help to reinvigorate the relationship between donors and African countries. And, as it supports investments with important country-level benefits, it could serve as an incentive for African countries to pursue reforms that increase their absorptive capacity, in terms of choosing and executing public infrastructure investments.

The Big Bond approach represents a much-needed update to the ODA framework – one that supports higher and more sustainable growth in recipient countries, while lowering the burden on donor countries. At a time when aid is under political pressure, perhaps such a bold approach to maximizing the efficiency of donor resources is exactly what the world needs.

© Project Syndicate, 2017.