Viewpoint

The Guyana economy like most other economies follows the classification of the United Nations System of Accounts. It has four sectors within which one could find all the industries and the business units that are part of the various industry groups. The four sectors are agriculture which is coupled with forestry and fishing, manufacturing as a standalone sector, mining which is paired with quarrying, and then there is the services sector. The size of the physical contribution of each sector to the gross domestic product (GDP) of the country is often used to classify and describe the country. Using GDP alone, Guyana should be classified as a service economy since services account for an average of 53 per cent of output while agriculture accounts for about 20 per cent. Yet, the country continues to cling to the belief that is an agricultural economy. This article seeks to examine what motivates Guyana to harbor this viewpoint about itself. The article will be presented in two parts.

Starting point

It seems natural for a country with abundant land and water to think of itself as an agricultural economy. Such a view could easily be reinforced by the historical use of the land and waterways of the country. Agriculture’s history in Guyana began with the Amerindians in British Guiana who hunted and engaged in subsistence farming. The capture and consumption of the game brought people together which made food consumption a community feature. The country’s history indicates also that, like most other countries, agriculture was the starting point of economics in the society. With colonialism as part of its history, any discussion of this matter would benefit from separating the colonial experience from that which came after independence in 1966.

could easily be reinforced by the historical use of the land and waterways of the country. Agriculture’s history in Guyana began with the Amerindians in British Guiana who hunted and engaged in subsistence farming. The capture and consumption of the game brought people together which made food consumption a community feature. The country’s history indicates also that, like most other countries, agriculture was the starting point of economics in the society. With colonialism as part of its history, any discussion of this matter would benefit from separating the colonial experience from that which came after independence in 1966.

Over the years of its colonial past, Guyana had a long experience with cacao, cotton, coffee and sugar, and more briefly, with tobacco. These crops were grown in abundance at various times in Guyana. Rice was there with lesser status and serving a different economic purpose. Without going through the progression of history, it should be noted that sugar surged to the top of the list of agricultural products when the British began to dominate the economy, and assumed a very strong and prominent position. As Daly tells it in A Short History of the Guyanese People, cotton and coffee plantations were converted to sugar plantations. The labour that was employed during that period was to service the plantations on which the various crops were cultivated.

Small

Each plantation had its own factory to process the cane into sugar for the principal purpose of meeting export demand. As a consequence of its long reign, some intimacy between people and sugar production must have developed through the passage of time. This awkward affinity to sugar is making it difficult for Guyana to see the fiscal damage being wreaked on the economy today by an industry that hardly had a future without the use of slave labour and relying on market protection. Keep in mind that Guyana had over 400 sugar estates at one time. Closures and amalgamations, as a response to competition and market forces, have brought the industry to the small number of estates in operation today. History should guide current attitudes towards the continued shrinkage of the sugar industry and the belief that agriculture reigns supreme.

The other surviving colonial crop of consequence in the Guyana economy is rice. Rice was first introduced by the Dutch Governor of Essequibo Laurens Storm van ʼs Gravesande in 1738 to supplement the diet of enslaved Guyanese on sugar estates. It took Guyana another 158 years thereafter to produce enough rice to start exporting the product. Exports of rice first went to Trinidad and Tobago. With time, markets were found in Asia and the USA. Progress in the diversification of rice markets was interrupted by the First World War and Guyana ended up expanding exports to the West Indies. The Guyana Rice Development Board reported on its website that by the end of the Second World War, Guyana had a virtual monopoly of the West Indian rice market, producing an average of 61,000 tonnes of paddy and exporting 23,000 tonnes of the product to the sub-region. It is this experience of rice in the West Indian market that led many to think of Guyana as being the breadbasket of the Caribbean.

Pre-eminence

It would be fair to say that rice and sugar owe their pre-eminence to the support that they received from the colonial powers who ruled Guyana. That is not to say that Guyanese were not engaged in other activities of an agricultural nature at that time, and enslaved Guyanese were eating other foods. In addition, documentation reveals that the first exhibition at which agricultural and industrial produce in Guyana was displayed occurred in 1898 at Victoria-Belfield.

The fact that other crops did not benefit from the resources and market reach of the colonial masters did not mean that they were unimportant to the livelihood of Guyanese. That lack of support meant that they did not attract financial resources and agricultural extension support as sugar and rice did to engender their growth and expansion during the colonial era. ‘Other crops’ remained largely at the level of subsistence farming, just enough to take care of one’s needs and then some. Sugar and rice were export-oriented which gave them added status over other agricultural crops. They were two of three of Guyana’s major exports at one point in time. They emerged as Guyana’s traditional crops, and the country was regarded as an agricultural based economy. These two crops continue to dominate agricultural output even though their combined weights inside and outside of the industry have declined.

Efforts at agricultural expansion

Another reason Guyana might see itself still as an agricultural economy has to do with food security and food sovereignty. While efforts to expand rice production came with the opening up of Black Bush Polder and Canal Polder and sugar tried to improve its productivity through amalgamation and the closing of estates and better field practices, some consideration was given to supporting non-traditional crops with the establishment of the Guyana Marketing Corporation (GMC) in 1963. Cattle rearing was also prevalent in the Rupununi area particularly during the late 1950s through to the 1970s.

Guyana’s first real attempt at broadening the agricultural base and to reinforce its profile as an agricultural economy occurred in 1972 under the Feed, Clothe and House (FCH) the nation drive. The FCH drive led to the formation of hundreds of cooperative societies that were involved in agricultural production. It also led to the development or strengthening of a variety of support systems, including the GMC which engaged in a variety of agro-processing activities and the establishment of the Guyana Agricultural and Industrial Development Bank (Gaibank).

Enormous opportunities

Guyana’s vast tracts of productive land presented enormous opportunities for growth in the areas of crops and livestock. The range of crops involved was wide and included various types of ground provisions, citrus, beans and fruits. The expanded production of these crops with a guaranteed market in the GMC was intended to meet a set of social and economic goals. The goals did not only include achieving food security, they were also aimed at increasing employment and strengthening the competitive position of the economy. Guyana had come to realize that rice and sugar were commodities where success depended on supply and demand in markets over which Guyana had little control. The foreign exchange earned from those commodities was spent on helping to maintain those industries and importing foreign-produced food. Guyana tried to reduce its dependence on foreign foods by adopting a mercantilist policy of import substitution. The policy was simple, export more and import less. In addition, export more value-added foods and less unprocessed primary commodities.

As a consequence, Guyana deployed various techniques that were prevalent during the heyday of mercantilism, namely high tariffs or physical restraints on imports while seeking to buy more intermediate goods for production. Part of the struggle was induced by the contradictions between mercantilism and liberalism since the policies ran counter to the policies of liberalism that had taken hold of the global economy by the late 1970s. Additional challenges came from exogenous variables such as conflict in the Middle East. Consequently, even more traumatic were the successive increases in the price that Guyana had to pay for oil following the imposition of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and their oil production and pricing will on the world. By the end of the 1990s, Guyana found itself buying oil at well over 300 per cent of what it was paying at the start of the FCH programme in 1972. The ambitions for value-added exports through agro-processing were dashed since energy was an important input into the agro-processing initiative and it was costing too much to access it.

Other factors such as number of persons employed, contribution to government revenues and number of persons dependent on the sector helped to reinforce the significance and image of agriculture as the dominant sector of the Guyana economy. (To be continued)

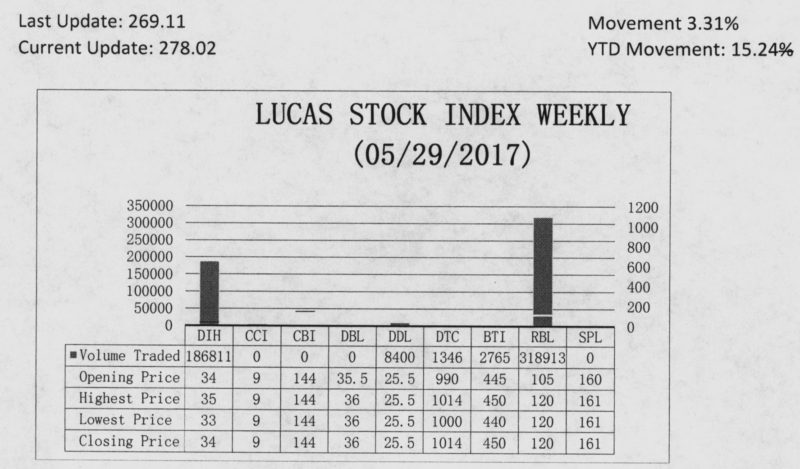

The Lucas Stock Index (LSI) rose 3.31 percent during the final period of trading in May 2017. The stocks of five companies were traded with 518,235 shares changing hands. There were three Climbers and no Tumblers. The stocks of Republic Bank Limited (RBL) rose 14.29 percent on the sale of 318,913 shares while the stocks of Demerara Tobacco Company(DTC) rose 2.42 percent on the sale of 1,346 shares. The stocks of Guyana Bank for Trade and Industry also rose 1.12 percent on the sale of 2,765 shares. In the meanwhile, the stocks of Banks DIH (DIH) and Demerara Distillers Limited (DDL) remained unchanged on the sale of 186,811 and 8,400 shares respectively.