“We use or produce oil but the contracts that make it all possible have been secret. Until now …..” This quotation which is taken from the blurb of the book Oil Contracts – How to read and understand them while a bit optimistic, does have a ring of truth about it. Freely available on the internet, this publication under a Creative Commons licence notes a change in the transparency dynamics of oil contracts under which oil companies and governments have historically used non-existent confidentiality clauses to conceal information from their citizens and the public at large.

“We use or produce oil but the contracts that make it all possible have been secret. Until now …..” This quotation which is taken from the blurb of the book Oil Contracts – How to read and understand them while a bit optimistic, does have a ring of truth about it. Freely available on the internet, this publication under a Creative Commons licence notes a change in the transparency dynamics of oil contracts under which oil companies and governments have historically used non-existent confidentiality clauses to conceal information from their citizens and the public at large.

Introduction

It bears noting, and perhaps periodic repetition, that the model (Petroleum) Production Sharing Agreement under which oil companies are granted licences for the exploration and development of petroleum imposes confidentiality obligations only in respect of petroleum data, information and reports obtained or prepared by the oil companies. Any statement to the contrary is not only misleading: it is false and untruthful. Transparency and the overriding public interest in such contracts have caused a number of such contracts to be made available both at the national and international levels. For example, the University of Dundee, Scotland; Revenue Watch Institute, an NGO; and the World Bank and others (resourcecontracts.org) are facilitating the process by collecting and disseminating them in searchable databases on the internet. It must be more than ironic that Guyanese have learnt more about their own oil resources and contracts from the US Securities and Exchange Commission than from the Government of Guyana. Neither law, logic nor the public interest requires or favours the continuing withholding of the oil contracts signed by the Government of Guyana ostensibly acting on behalf of the people of the country.

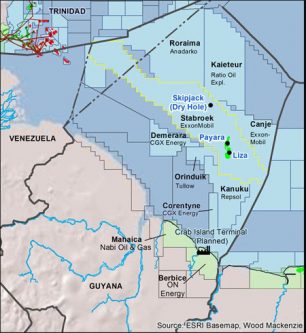

In today’s column we offer some additional information and a map of the exploration and production contracts currently in force.

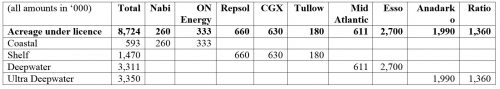

The information on the contracts listed in last week’s column was provided by the Guyana Geology and Mines Commission which continues to have responsibility for the petroleum sector pending the establishment of the Petroleum Commission for which a Bill has been tabled in the National Assembly. The map shows that CGX Energy has a Demerara block which does not appear in the list published last week. Efforts will be made to seek clarification of this difference. Subject to this, an analysis of the information is as follows:

While ExxonMobil is shown as having 2,700,000 hectares, it is also the Operator for the Mid Atlantic licence for the Canje Block and for the Kaieteur Block in both of which it is also a Joint Venture partner. This means that in total ExxonMobil is involved in 54% of the hectares under current licence. Whether this was purely accidental and made without consideration of the implications, Guyana’s prospects and their success are now heavily dependent on the performance by ExxonMobil in the Guyana fields. Despite the significance of the Liza and the Payara fields and the prospects in the other areas in which the oil giant is involved, ExxonMobil will never allow itself to become overly dependent on any single country. No one should blame them. Oil companies have had several experiences of unfriendly and at times hostile action by host countries across regions and continents. As Venezuela recently showed, those experiences are not just the stuff that make the history of oil so fascinating – whether for the resourcefulness of individuals, the dramatic changes in technology, the greed and arrogance of oil companies or the greed and arrogance of host countries.

While ExxonMobil is shown as having 2,700,000 hectares, it is also the Operator for the Mid Atlantic licence for the Canje Block and for the Kaieteur Block in both of which it is also a Joint Venture partner. This means that in total ExxonMobil is involved in 54% of the hectares under current licence. Whether this was purely accidental and made without consideration of the implications, Guyana’s prospects and their success are now heavily dependent on the performance by ExxonMobil in the Guyana fields. Despite the significance of the Liza and the Payara fields and the prospects in the other areas in which the oil giant is involved, ExxonMobil will never allow itself to become overly dependent on any single country. No one should blame them. Oil companies have had several experiences of unfriendly and at times hostile action by host countries across regions and continents. As Venezuela recently showed, those experiences are not just the stuff that make the history of oil so fascinating – whether for the resourcefulness of individuals, the dramatic changes in technology, the greed and arrogance of oil companies or the greed and arrogance of host countries.

ExxonMobil’s business activities in Guyana, as indeed of other oil companies engaged in the sector, will always have to fit into their broader international operations. They will develop and operate at their own pace having regard to the price of oil, the wishes of their shareholders, broad policy imperatives, and other internal company considerations. One of the worst mistakes we can make is trying to force their hands since they will expect as much in return.

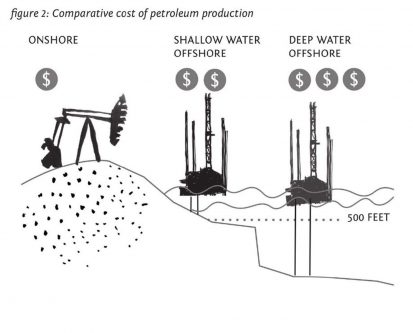

Another interesting and perhaps not unrelated feature of the licences is that 6,661,000 hectares or 76% is located in deepwater or ultra deepwater. The Geology and Mines Commission defines deepwater as anything between 300 metres to 1,000 metres and ultra deepwater as any depth over 1,000 metres. While the technology has come a long way since oil exploration moved from land to water in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, confronting and managing the challenges of deepwater drilling are neither uniform nor cheap. Apart from, or perhaps attendant with, the technological challenges of deepwater exploration and production are huge risks and high costs.

The structure of the petroleum contract requires that cost oil be deducted by the oil company before any profit oil is available for sharing with Guyana. There may be a minimal upfront payment to Guyana and perhaps some restriction on cost oil to ensure that Guyana does receive some profit oil even if there is no profit. That discussion will take place in a later article but as the following diagram shows, deepwater oil activity is estimated to cost three times as much as onshore activities.

Source: Oil Contracts – How to Read and Understand Them, OpenOil.net

Source: Oil Contracts – How to Read and Understand Them, OpenOil.net

With oil prices at below US$50 per barrel and not likely to increase significantly no earlier than 2018/2019, the best that Guyana can hope for is that by the time first oil is produced, the price will have increased significantly.