In today’s column we conclude our review of the science and technology which goes into the prospecting, exploration, development and production of petroleum products. Readers will recall that we looked last week at the formation of the building blocks of petroleum and discussed at some length how they are formed. The challenge as we noted, was how to locate the rocks where hydrocarbons are stored in sufficient quantity to be commercially viable. It is all about science and technology.

As Michael Forrest writes in Deepwater Petroleum and Exploration and Production – a Non-Technical Guide published by Penwell of the USA, the technology boiled down to seismic data, especially 3-D data provide a quantum leap in allowing the prospecting company to determine the probability of success. This process is a four stage continuum of acquisition, processing, display and interpretation of data.

Some oil companies contract to vendors many of the early stage services. Some processing takes place on the vessels as sound wave echoes from the boundaries between various layers of seabed, back to the surface where they are picked up by hydrophones. Here is the essence: the deeper the layer, the longer the echo takes to reach a hydrophone. Moreover, and this is critical as well, the various layers of the subsurface have different acoustical properties. The unique velocity and density of each rock layer affects the strength of the echo.

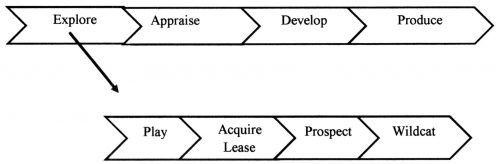

The process can accelerate based on how encouraging the signs are but as the prospects improve more resources are expended to move the process along. Some stages are extremely secretive and are often described by various code names. The process from beginning to production is shown below.

The top layer is a four-stage process but the exploration stage itself has four stages that lead to a recommendation for a wildcat well. The reason for this ultra-cautious approach is because the geologists are aware that the exploration phase is quite costly. They would want to make sure as best as they can that the prospects are indeed good. In the case of a deepwater well, the costs and the risks are even greater and no decision would be made until everyone is on board and as the process moves forward, the team becomes even larger since once drilling is involved, additional issues such as health and safety and environmental impact concerns arise. But the caution does not stop there. Even when the well has been drilled and the results are positive, the target has to be appraised for commercial viability, triggering another wave of expanded spending.

We can assume that ExxonMobil has gone through all the hoops and it and others are doing the same with other blocks. Such activity takes place away from the glare of publicity and that explains why the May 2015 announcement by ExxonMobil took the country by surprise. But the process was a long time in the pipeline. The ExxonMobil Agreement published by the Stabroek News is dated June 14, 1997. The company’s announcement was made almost 18 years later!

One last bit of theory before we delve into some practical issues later in the series. ExxonMobil has announced that it would be utilising a Floating Production Storage and Offloading (FPSO) system. As its name suggests it is a floating contraption that allows oil rigs the freedom not just to store oil but also to produce or refine it before finally offloading it to the desired industrial sectors, either by way of cargo containers or with the help of pipelines built underwater.

Given the interest which Guyana has been showing in oil by 2020 which coincidentally is elections year, the FPSO is the ideal choice.

Next week we will review the ExxonMobil Prospecting Licence from 1997 against the Petroleum (Exploration and Production) Act.