After a week has passed, citizens still do not know exactly what happened at the Camp Street Prison last Sunday, or the timeline of events. Earlier last week it was said the footage from the cameras inside the jail had not been studied as yet, so no analysis was possible, but one would have thought that by now that would have been done, and some kind of basic chronology would have been established. Or is it that even after studying the footage the authorities themselves don’t know exactly what transpired and in what sequence; or conversely, if they do know, they are too embarrassed to make that information public? Without this critical data, it is difficult to understand what precisely went wrong, whether there was dereliction on anyone’s part, whether any of the management procedures were defective, whether the riot and arson could have been prevented or interrupted at any stage, and so on.

As the week progressed, snippets of information were revealed bit by bit, sometimes from the perspective of those who were present that day in a particular location, but these did not amount to anything like a coherent overall view. Further-more, what the public was told ‒ including by the authorities ‒ was sometimes contradictory. While all kinds of times have been flying around from various sources about when the disturbances started, Stabroek News’s best guide to the beginning of the trouble came from kitchen staff in the late afternoon of July 9 who told our reporters that the attack began during the scheduled dinner period around 3 pm. “It was a vulnerable time,” one of them was quoted as saying,” because the cells were open and they were all “coming out”.

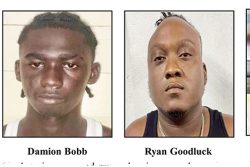

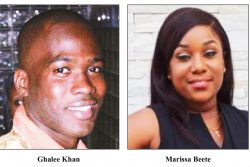

No one in authority has had anything to say about this. Is the public to understand that all, or most of the cells were unlocked, and the protocol was for the prisoners to go in lines, perhaps, to collect their dinner? Or was it that they were allowed out in sections and not all at once, and that certain categories had their dinner brought to them? Certainly the media were told by Prisons Director (ag) Gladwyn Samuels that Mark Royden Williams (thought to be the mastermind) was in a cell on his own, and solicited help from fellow inmates to break out. When asked how many prison officers were on duty that day, Mr Samuels answered that forty were scheduled to be working, although he could not say exactly how many were actually present, because the log book had been destroyed in the fire.

Clearly, collecting food is a very dangerous time, even if it only involves the less high-risk prisoners, because you can never be sure that they are not part of a conspiracy, as conceivably might have been the case with some of them in this instance. So exactly how many officers are supposed to man the dinner arrangements? Even without the convenience of a log book, it cannot be beyond the capacity of the senior officers of the Guyana Prison Service to find out who was actually on duty that day, and if there were enough warders in the yard at the time. Whether or not the full quota was there, they would surely know the sequence of events, and exactly how matters got out of hand. They could supply a perspective that even the closed circuit cameras might not provide, but as said above, the public has not been made privy to any of that.

Warders in other parts of the prison did not get much warning of trouble – certainly not those on the front gate, through which the four key prisoners made good their escape after overpowering them. In addition, several witnesses placed the beginning of the riot nearer to four o’clock than three o’clock, describing noise and then the alarm sounding. One unnamed warder did tell this newspaper that it was a few minutes to four when they heard what sounded like “things crashing”. It seemed as though improvised weapons were being used in the condemned section to hit out the boards, our reporters were told, and then those in the “strong cell”, ie, remand capital offenders, came into the yard, and then came running “Wild West toward we”.

One could always hypothesise, of course, that those inmates who were free with a view to collecting their dinner (or who had collected their dinner already), used the various home-made weapons they had amassed to break out the more dangerous inmates.

The significance of a timeline lies in the fact that when prisoners set their mattresses on fire in the March 2016 unrest in Lot 12, seventeen of them died because they were locked in and could not be extracted in time. On this occasion, however, all the prisoners were loose, raining rocks and objects of one sort of another down on the fire officers ‒ who had to tackle the fire from outside the security fence as a consequence ‒ and the prison officers who were trying to get them out of the jail. It was around 5.45 pm when Mr Clifton Hicken of the Guyana Police Force arrived and took over evacuation from the inside the prison, and then when the heat became too intolerable for the rioters, a ladder was placed on the fence some time after 6 pm so they could evacuate, which they did willingly by that time.

So exactly how did the entire prison population come to be free to roam the compound? For what proportion of them were the cells open, and how many others broke out, or were broken out? And how many improvised weapons were involved, and how long did it take the prisoners to accumulate them? Just when did the last search for weapons take place? Whatever the answer to the last questions, it is worth reiterating that it does not seem to be the case that anyone had to be rescued from a cell because of the fire. Or was everyone free – or almost free ‒ before the fires were set? And then how were the fires set? Was any kind of accelerant involved, and if so, how did the prisoners get their hands on that? Is one to presume that in planning their escape, the masterminds took measures to ensure that no one would die in the fire as happened last year, viz, by accumulating ‘jukers’ and the like to prise out the ancient wooden boards of some cell walls before the flames took hold?

The media were told that the prison would not have burnt down if it had not been for the prisoners denying access to the fire officers. While given the water situation that might have been an overly sanguine assessment, particularly when the wooden walls would have been like tinder. That aside, are there security lessons to be learnt from this disaster in terms of the regimen in place at times of vulnerability for staff? Did the fact that it was a Sunday, for example, affect the size of the officer complement?

One somewhat reassuring item of information was conveyed by Mr Samuels, who said all the firearms in the armoury had been accounted for, and that although one weapon was missing from the Operations Room, that might yet be found among the rubble. One trusts he is not too optimistic; there is one lone account which said the escapees were seen with two guns. The other one, it is known, was seized from a prison warder.

Much has been said this past week about officers acquiring intelligence of what is being planned in prisons. If the Police Force is anything to go by, then there might not be any great success for the Guyana Prison Service in that department. In addition, of course, overcrowded prisons are rife with rumour, not to mention genuine conspiracies which owing to their impracticality have no hope of coming to fruition. The point is, no matter what is being planned, a prison service must have the kind of systems in place which would make it difficult for the plotters to put their schemes into effect. Were such systems in place in Camp Street? No one beyond the security fence really knows.

Having said all that, of course, there is no denying the especial courage of the prison officers on duty that day, and indeed, of the members of the Fire Service and security services as well.

Where the Fire Service is concerned, the fire or fires seems to have begun some time around 4 pm. Fire Chief Marlon Gentle told reporters that when the fire personnel arrived, they were faced with four simultaneous fires, although from what Stabroek News saw at the scene they may conceivably have been lit in succession. The first tender this newspaper saw appeared somewhere around 4.15 pm.

Local residents said the two fire tenders they saw were soon out of water, and had difficulty accessing other sources. The water pressure in the hydrant at John and Bent Streets was too low to be utilized, and it was not until 9.30 pm, said one resident, that Guyana Water Inc put something on it which allowed the Fire Service to attach a hose. Furthermore, another resident told our reporters that there was an unmarked hydrant (which he showed the fire officers), on which he had been trying to get the GFS and GPS to place a marker for years.

Both those services, of course, would have regarded a hydrant as coming under the jurisdiction of GWI, which, if true, would have been an unfortunately narrow approach. Having said that, however, where there are important public buildings not to mention dangerous facilities like the prison in the middle of the city, GWI should make it its duty to ensure that the hydrants there are working. Equally important, it should have a regime in place for emergencies, so the water pressure can be increased quickly on request. It is not acceptable to have this done hours after a fire has started – more especially when the building involved is the Camp Street jail. Certainly the water utility was one public entity which appeared woefully unprepared for events, and seemed in need of a reference manual of emergency procedures.

Save for the burning down of the Prison Officers’ recreation centre, where prisoners should not have been placed given the circumstances, the evacuation was competently handled, for which the prison and security services can take credit. For the rest, in terms of the civilian authorities and what should have been done following last year’s tragedy, but was not done, there is plenty of blame to go around.

In the meantime, would Minister of Public Security Khemraj Ramjattan, or anyone delegated by him, make it his business to inform the public about what really happened on July 9?