British-American poet W H Auden was talking about the masters of art, the great painters and their study of suffering and the human condition. His persona might have been an art critic, a guide walking visitors through the Royal Museum of the Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, in December 1938, and deconstructing the paintings on show. He makes reference to a number of works by these “old masters”, in particular Belgian sixteenth century painter Pieter Bruegel. As he explains, he pauses by Bruegel’s “Landscape with the fall of Icarus” pinpointing it as an example of the fine precision and accuracy of the work of the old masters who never got it wrong.

British-American poet W H Auden was talking about the masters of art, the great painters and their study of suffering and the human condition. His persona might have been an art critic, a guide walking visitors through the Royal Museum of the Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, in December 1938, and deconstructing the paintings on show. He makes reference to a number of works by these “old masters”, in particular Belgian sixteenth century painter Pieter Bruegel. As he explains, he pauses by Bruegel’s “Landscape with the fall of Icarus” pinpointing it as an example of the fine precision and accuracy of the work of the old masters who never got it wrong.

Fast-forward to Castellani House and the National Gallery of Art, Guyana in Georgetown in July, 2017, where the Guyana Visual Arts Competition and Exhibition (GVACE) is on show. As one walks around the gallery deconstructing the more than 200 pieces of art, representing the output of the nation’s contemporary artists in six disciplines, one may very well make the same observation about “the old masters” of Guyanese art – “they were never wrong . . . how well they understood” the human position.

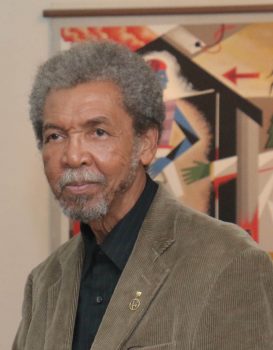

In particular, one may pause and make particular reference to the works of painter Stanley Greaves, sculptor Oswald Hussein, photographer Nikhil Ramkarran and craftsman Michael Khan. Each of these men has been notably outstanding in his field for a long time, and they certainly did not get it wrong in 2017 as the winning prizes in the GVACE this year were fairly well dominated by “old masters”.

Those were the winners in their respective fields. But when one goes further to add those who were awarded second and third places, and those shortlisted, this dominance is complete. Take for instance – Greaves and Desmond Ali in both painting and sculpture, Betsy Karim (painting), Carol Fraser and Winston Strick (fine craft), it is remarkable how these experienced artists, who have long been prominent in Guyanese art, did not get it wrong in this year’s competition. Putting prizes and shortlists aside, and studying the works that they entered in the competition, one can truly remark that they well understand the “human position”.

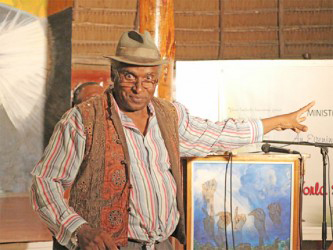

What is more, the Management Committee of GVACE conferred a 2017 Lifetime Achievement Award on Jorge Bowenforbes, a painter who straddles important ages in Guyanese art, and this could be discerned in the works of his on show in the exhibition. There is, in Bowenforbes, the landscape preoccupation of the pre-independence era, the realism, as well as the 21st century excursions into modernism. As an old master, this painter’s work is instructive about the art of the nation past and future.

However, while those master craftsmen have demonstrated why they are leaders in the field, the entire exhibition is an excellent demonstration of the state of Guyanese art today. This may be found equally well in the work of several newcomers and rising artists who in many ways represent the new waves in the art. There is much to remark at about the formal and stylistic preoccupations, which show marked shifts from an earlier prevalence of realism, and the emergence of a greater tendency to experiment and to mix realism with several innovations in abstraction. What is more, the study of subjects shows approaches from many different angles and perspectives, which make those subjects much more interesting and worth looking at.

This is evident in the works of the other winners and shortlisted artists such as draughtsmen Compton Babb, Walter Gobin and Dominique Hunter, and photographers Michael Lam and Aisha Jones. (Vandyke David, Andrew Sampson and Staffon Williams were the winners in Ceramics). Critic and artist Alim Hosein makes particular mention of the new waves and “the emergence of new names” since 2014. In counter-point to this year’s return of the more established artists, he draws attention to the several awards won by these emerging names and in particular, to the Promise Award given each year by GVACE. (Hosein, “Keeping the Flames Alive”, GVACE Catalogue, 2017)

This new development is particularly marked in photography, for instance. This year’s winner, Ramkarran, is a lawyer by profession, but has taken up photography in very serious way. He leads the field in the study and approaches to subject that constituted the most remarkable feature of Guyanese photography recently. Hosein mentions the boost that this emerging art form gives to Guyanese tourism, but there is a far more interesting twist to it than the traditional landscape, flora and wildlife famous in Guyanese photography for ages.

The art of this photography foregrounds ‘ordinary’ subjects made infinitely interesting by a cameraman as artist – a point of view that makes an ‘ordinary’ scene a work of art that tells stories, makes suggestions and excites the imagination. This is the case in Ramkarran’s “Porknockers Picking”. The title is suggestive and transports one into a world that appeals to the imagination. There are men with the roughness of the “bushman” about them in sharp contrast to the elegantly dressed attractive young lady who is also in the picture, apparently just by chance.

It is similar to the kind of study found in the angle from which the historic chimney is taken through a padlocked gate in “Chateau Margot” by Michael Lam. This “point of view” that draws so much attention to the picture is also found in the drawing “the Birdmen” by Walter Gobin.

The 59 paintings in the exhibition provide evidence that neither landscape nor realism dominates Guyanese painting anymore. At the same time, almost paradoxically, many painters try to mix realistic figures into abstract imaginative compositions and into innovative constructions such as “Diwali Festival of Lights,” which is typical Betsy Karim. These very large paintings consist of very intricate realistic images covering a crowded canvas to fashion an imposing work with distinct identity. There are many other very large canvases such as Elode Cage-Smith’s “Hurtle” and “Momentum” exploring colour and the imagery of motion/movement. These studies in form include an attempt by Desmond Ali to produce on canvas the kinds of themes of resistance and struggle explored for several years in his relief sculpture.

The very distinctive signature pieces by Greaves recall or relate to earlier paintings which could very well belong to suites and preoccupations spanning decades. A good example of this is “Mazaruni Black Ants and Diamonds” reminiscent of his “Hearts and Diamonds” series. But like George Simon has done repeatedly, Greaves moves into new studies which bear his distinctive idiom but betray new concerns. This is the case with “Rupununi Agates” which play on imagery taken from the agate with its layers and patches. There is symbolic reference to the Rupununi as well as motifs drawn from the Amerindian petroglyphs – an imposing painting noted for its variations of shapes. Here is a work reaffirming the metaphysical quality of this painter.

Greaves has returned with a reminder of his exalted impact on national art, and so has Hussein. Hussein’s work in this exhibition represents forms that have developed in Guyanese sculpture over what is by now a long period, but with new pieces that dominated the 2017 competition in sculpture. “Silence” stands out as another masterpiece with the distinctive ethnic characteristics of contemporary Amerindian art in Guyana. It is the Hussein of old, recalling the impact he made some 27 years ago with the work that heralded the meteoric rise of Lokono sculpture. “Silence” is authoritative in the spiritual quality which is a striking feature of Hussein’s work. It bears the marks of the rainforest with its strong elements of animism, its shape-shifting potential and the very intricately carved motifs around the body of the work.

There is also the recent emergence of patriotic art. This is prevalent among the sculptures – Francis Ferreira, Shimuel Jones and Marvin Phillips – and in a few paintings and drawings. But this patriotic art reaches its most significant explosion in works such as Fraser’s “Burgeoning Steps,” Khan’s three-piece “Rumination” suite and Strick’s pieces, which made a significant success of the newly-fashioned category of fine craft. It took these “old masters” to achieve what Hosein explained: “Textiles was expanded into a new category” which “broadened the scope of the competition to allow . . . other persons whose work would normally be deemed ‘craftwork’ to enter.”

Khan, who had not been heard from for quite a while, revealed so far his magnum opus – surprise masterpieces that he worked on during his sabbatical year from the University of Guyana. They suggest extremely painstaking thorough work in mixed media, very labour intensive but carefully crafted colourful tapestries telling tales of national pride. Fine craft has thus widened the scope of areas of art that have come to wider national attention, both dignifying and legitimising them. But it has done so in quite flamboyant fashion, given the commanding quality of Khan’s work.

This is an extremely large and extensive exhibition and a major statement on contemporary Guyanese art. There are a few developing areas not particularly well represented because much of the work did not come forward. Some of these have been advanced by the same “old masters” with an indication that they were new areas opening up. These include elements of East Indian art advanced by Bernadette Persaud especially, and by Philbert Gajadhar. The few signs of continuation come from Karim, who has not confined herself to this brand of art, and Darshani Kistama whose work is entirely placed there.

While the sculpture was not so very wide in scope or numbers, painting, as expected, reflected the breadth and variety. That category is always elusive when one is looking for neat generalisations. Recent exhibitions have shown the diversity of post-independence Guyanese art, but it has not been as easy to pin this down in this exhibition. It was a competition that invited all comers and not all the work was very successful. It certainly revealed enough to show the trends towards abstract art, the increasing experimentation and much post-modernism.

As would be normal, many of the leading talents and the established artists were not there. However, most of the new developing brigade were there, although the wave of Amerindian art was underrepresented. Despite the considerable promise revealed in the exhibition, and the continued work of the newer generation, in 2017 it was the old masters who asserted their authority upon the proceedings, dominated the prizes and made the major statements.