This week Roger Seymour concludes his visit with Guyana’s junior squash team coach Carl Ince. Two weeks ago (July 9) he explored the coach’s life in England.

August, 1995

The sun was setting as Carl Ince and his wife Maggie sat at the door of their ‘caravan’ looking up the rising knoll on their property. They were thousands of miles from Manchester, facing another bundle of challenges: remigration, farming, no electricity, no running water and confronting the might of nature itself, in the form of pristine jungle. Clearing it was energy sapping; Ince toiled alongside the hired workers, in the heat of the blazing sun and the almost daily rain.

The caravan was in fact the 40 ft container they had purchased to ship their household belongings when they decided to move to Guyana. Initially stored in Plaisance, it had been modified – louvre windows, two bedrooms, a kitchen, and a washroom installed – and moved to the farm-in-development as soon as a sizable area had been cleared and a road cut from the Linden/Soesdyke highway. Once the farm was up and running, they planned to build a house within a couple of years.

The seed for Ince’s return had been planted during a squash game in Manchester, in the late 1980s, with then government minister Robert Corbin, who suggested his contribution to his birth place’s development could be as a squash coach. Whilst the wild sales pitch was germinating, on one of his visits to his Dad, who had returned home in 1974 to take up a job as chief remigration officer, Ince applied to the Lands and Surveys Department for land. Now, here he was venturing into planting pineapples.

Squash ever lingering in his thoughts, he soon began constructing a court – there was no house yet. Once the court was finished, he often practiced alone, staying in shape.

He focused his energy and efforts on developing the farm, hardly going to Georgetown (he is still unfamiliar with the lay of it), heading instead to the mining town of Linden for his supplies.

Whenever Maggie returned to England to visit the children, Ince would be alone with the two horses, Son Boy and Sueling, the affectionate names he had often used for his first two children, when they were growing up.

Farming can be a hard taskmaster, as Ince discovered at a hefty cost along the way. The disappointments can be many, varied – weather, pests, the unforeseen, the unexplained, suppliers, buyers, unreliable workers – and enough to test one’s patience and sanity.

“Have you ever heard of El Nino?” Ince enquires, pausing for a moment. ”One day it got so hot, everything just started burning. The entire crop of pineapples all burnt to the ground, every single plant burnt completely. I just stood there, helpless, unable to do anything,” he said.

The experience would have destroyed the spirit of many an aspiring farmer, it only deepened his resolve to succeed. But pineapple growing was capricious, so he sought an alternative focal point for the farm.

Surapana Club

One day in 1997, Ince was at the National Insurance Scheme office in Linden making enquiries about contributions for his employees, when he nonchalantly asked the clerk if he had ever heard about the game of squash. To his utter amazement, the clerk calmly replied, “Yes, actually my boss, Willo, plays here in Linden.”

Within an hour, Ince found himself in Watooka, standing in the ‘T’ of the court at the Surapana Club, the enclave of the senior managers at the bauxite company. He had to badger the bewildered woman in charge of the club to open the court, as she couldn’t understand why anyone would just want to go stand there. Ince stood alone in utter silence, savouring his discovery of a squash club in his neighbourhood. Little did he know that his world was about to change forever.

As he was leaving the building, he encountered former national cricketer Orin Gordon. The towering ex-fast bowler was delighted to meet Ince and immediately invited him to join the group who got together on Saturday mornings.

“At that stage, Dr [Stanley] Marcus and I were raw, just whacking the hell out of the ball,” Gordon reflected over the telephone, a few nights ago. “We had played in a tournament at the Georgetown Club the previous year where we were completely outclassed. After regular sessions with Coach, we returned the next year and shocked the hell out of them. I even got to the finals, beating Nicolette Fernandes in the semi-finals.”

The folks at the Georgetown Club asked about their transformation and on learning that they had been reaping the benefits of a British Certified Level Two squash coach, enquired about his availability. When this was related to Ince, he assured his dedicated students that he wasn’t going to leave them and relayed during a visit several years before, Corbin had taken him to the Georgetown Club for a game of squash. He has then returned a few days later on his own, but whilst practicing was informed that he was not a member and was asked to leave. He did and vowed never to return.

Soon after, the folks from the Georgetown Club showed up at the now defunct Surapana Club and Marcus tracked Ince and his wife down at a friend’s house in Linden.

A week later, Bobby Fernandes, then Guyana Squash Association president, was introducing him to a gathering at the Georgetown Club and publicly asking him to consider taking up the post of national junior squash coach. It was three months before the 1998 Caribbean Area Squash Association (CASA) junior championships, scheduled for the Bahamas.

When he questioned Bobby about his offer despite never having seen him coach, his reply was, ‘I know a racehorse when I see one, I don’t have to see it run.’

Today Ince still marvels at the selflessness of his two students from the bauxite town, who told him that the children on the national team needed him more than they did.

Hope

“Boy, we get licks, real licks,” he recalled. However, there was a glimmer of hope: Kristina King won the girls under-12 championship, Guyana’s lone title; Nicolette Fernandes was a member of the team. A year later, in Trinidad, the girls snatched the title from seven-time defending champions Barbados.

In 2000 Guyana were overall champions, as the girls successfully retained their crown in Bermuda. Over the next four years, their arch rivals, Barbados, took three overall titles, with Guyana interrupting their domination by sweeping both the boys and girls titles at home in 2003.

Alwyn Callender, a Guyanese corporate lawyer then practicing in London, noticed the marked improvement in the local junior players during one of his annual visits in early 2001. Callender approached Ince, introduced himself, and expressing admiration and appreciation for his work and offered to sponsor him for the level three squash coaching certificate in England.

“I was stunned. A complete stranger offering to pay for everything,” Ince reflected. Kathy Shuffler, a former junior player then working at BWIA insisted on getting the ticket, and by April he was a Certified Level Three Coach, passing the first test with such a high score that his examiner exempted him from the second part of the evaluation. However, his euphoria was short lived, as within 15 minutes, he received news that his mum, Rose, whom he had seen just a few days before, had passed away.

In 2001, the house on top of the hill was completed. Ince had built it with his own hands; bending the steel for the foundation, mixing and pouring cement, logging lumber, cutting boards, pulling beams into place, hammering nails. It had been a labour of love.

Callender moved to New York in 2003, and later visited home to become a certified squash coach. “Do you know what that did for me? Being able to give something back to this man who had helped me, a complete stranger,” Ince mused.

Callender would go on to become an international squash referee and was one of the eight at the 2012 World Squash Championships in Doha, Qatar.

On July 15, 2004, Ince attained the Elite Level Four England Squash Certification, a rare distinction, thus making him eligible to certify coaches up to the level two standard.

Winning streak

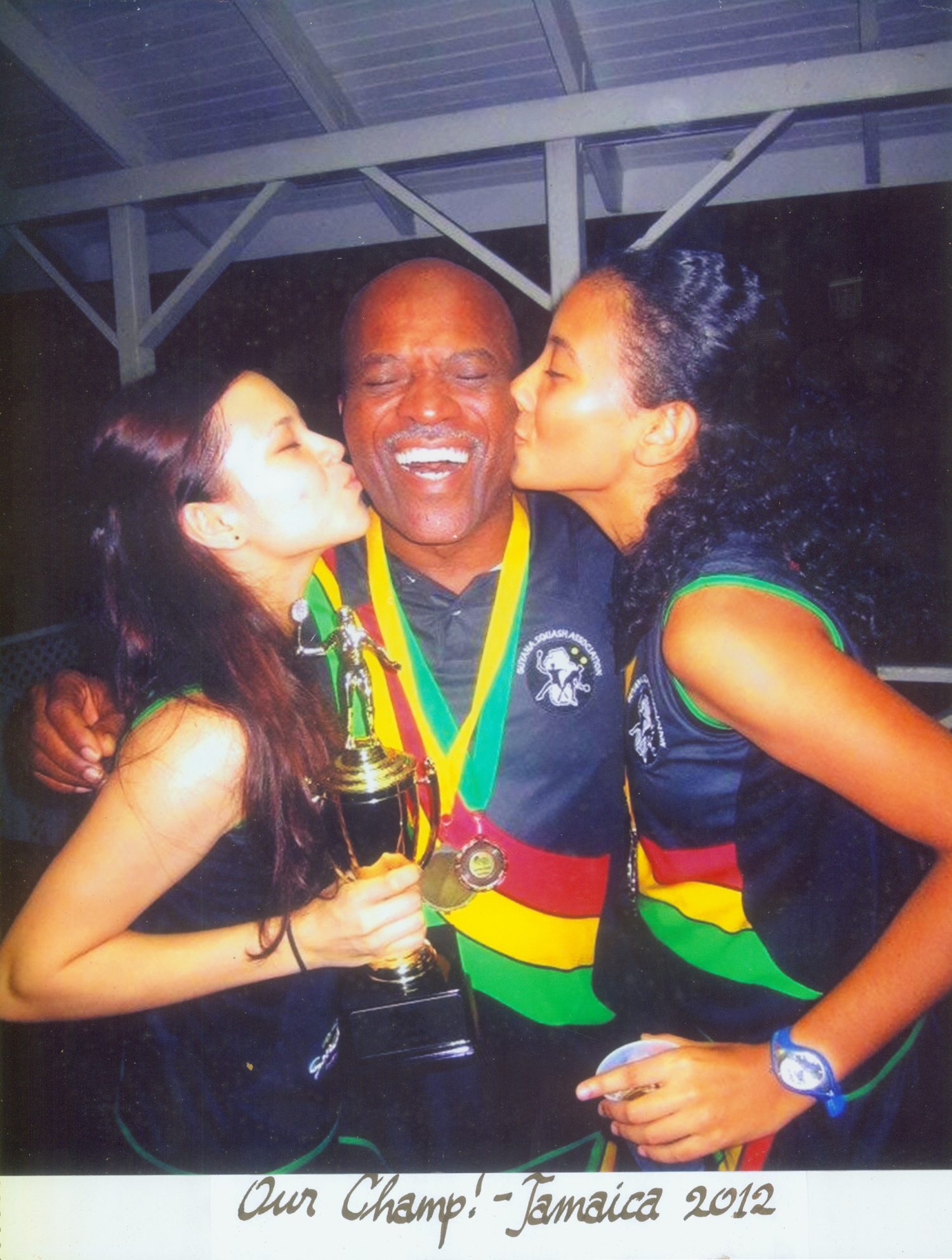

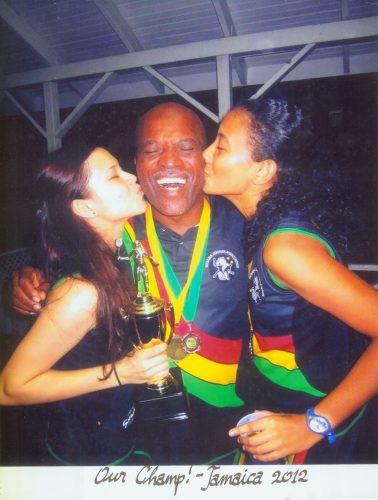

Under Ince’s guidance, Guyana embarked on a 12-year streak of winning the overall team championships, beginning in 2005 in Trinidad, and only coming to an end two weekends ago, here at home. During that time the girls achieved an unprecedented nine-year streak of titles (2006-2014), with the boys winning four straight from 2013 to 2016. The team swept both titles in Bermuda (2008), Barbados (2009), Guyana (2011), Trinidad (2013) and Bermuda (2014). Ince has coached 18 individual champions who have won a combined total of 49 Caribbean Junior titles.

The memories are wonderful and the achievements numerous. Asked if any particular moment stood out, Ince ponders for an instant, “Hmmm,” his smile broadens, “Tortola, 2007…”

Deje Dias, raconteur extraordinaire, joins the commentary: “I was a pagaly little boy, just a reserve on the team, under-14 back up, not expected to play and then Kristian Jeffrey, under-19, our best player gets hurt during the singles, pulls a muscle, and there was a lot of politics… The Trinidadians objected to us knowingly putting in an injured player and called a meeting. A vote was taken and if could be proven that we had used an injured player, Guyana would be disqualified. I lost my cool (Coach is incredibly calm).

“I found out that I was playing at midnight. I was so nervous, I couldn’t sleep. We were in a group of three with Cayman Islands, we had lost to them 3-2, and needed to beat Barbados to advance to the next round. (In fact, Pool B comprised four territories, with Jamaica as the other team). Abishek [Singh], our under-13 player who was expected to win, lost the opening match. Then I had to play Nkosi Ross, a six-footer, with lots of CASA experience. I was blown out in the first game 0/9.

“The Bajan coach left to go watch the Bajan girls playing against Bermuda. Coach put his hands on my shoulders during the 90-second timeout: ‘You remember the drill we used for playing against the six footers, Uncle Jo-Jo Mekdeci and Burch-Smith? Just imagine you playing against them, you are going to be fine.’ I won the second game 10/8, I was on top of the world I had won a game. This was unbelievable! Then I won the third game [9/5]!”

Ince: “The Bajan coach returned during the fourth game. ‘What? This game still going on?’ I looked at him: ‘Deje is winning 2-1, and is leading in the fourth.’”

Dias: “I have match ball. I am so nervous, I can’t even serve. I lose service. Miraculously, I get a second match ball. I make a hopeless serve, Ross doesn’t kill it, we rally, and eventually he plays it into the tin. I won [9/7]. Everyone is screaming, Uncle Kevin [Jeffrey, Kristian’s dad] and Uncle Andrew [King] are tossing me into the air and catching me, they throw me to my Mum, they throw me to Coach and he catches me. The Guyanese tek over de place, we making noise, everyone is screaming.”

Ince: “I lost it. I was banging on the rail so hard that my watch, a birthday gift from my wife, was shattered, the back broke, the battery was gone, the strap broke, it was in pieces everywhere…”

Alex Arjoon (U-15), Oliver Kear (U-17) and Raphael De Groot (U-19) swept the rest of the Bajans aside for a 4-1 victory. Trinidad won the boys’ title, but with the ‘Mudhead Girls’ taking the title, Guyana retained the overall title.”

Dias picked up the pieces of the watch and put it back together. The Amadeus still doesn’t work, but he still takes it everywhere.

During his tenure as National Junior Coach, Ince achieved phenomenal results with four different teams. As the former West Indies Test player and commentator, Reggie Scarlett once said, “Talent dries up, luck runs out, and then what? You better have a system of coaching and development in place. Only way to continue producing players.”

Elevated

Ince, in his own way, has elevated the standard of squash in Guyana and the Caribbean. The two Barbadian coaches of the just crowned Boys and Girls Champions, Rhett Cumberbatch and Marlon White were certified by Ince a few years ago. His calm, quiet but firm approach coupled with great patience and understanding of each player’s strengths and weaknesses serves to build a bond with each player. His tactical knowledge of the sport, appreciation for fundamentals, emphasis on hard work, repetition and drills assist his students to reach another level.

Nicolette Fernandes who played professionally for over a decade, rising to number 19 in the world rankings, will always consider Ince as her coach, despite having being tutored at one time by David Pearson, the former English national coach. Throughout her career on the professional circuit, Ince was able to prepare her every situation, briefing her in advance, during her off-season visits back home.

We are sitting at the rustic dining table (yes, he made it) in his house, three days after Barbados’s conquest of the Guyanese teams at the CASA championships. Three young charges of next year’s team are in residence, lounging in the living room, anxious to do the next round of drills. He demonstrates the drill he wants them to execute in his casual, unassuming manner. The future champs sprint away.

Ince ambles downhill pass his five stables. The caravan is straight ahead, still in its original position, now an empty shell, a stark reminder to the trials of remigration. It squats between the workers’ residence and the two squash courts, overlooking the creek. He gathers the reins of one of the horses trotting around, pats its neck, speaking easily, displaying innate equine care.

“If I could have grown grass here, I would have been a horse breeder,” he says.