By Estherine Adams, Clare Anderson, and Kristy Warren

In August 1956, the Director of the Prison Administration of England and Wales, R.D. Fairn, arrived in Guyana. The British secretary of state had directed him to report on the state of the jails, to review conditions, and to recommend action. At the time, Guyana was a British colony (British Guiana), though following the establishment of an interim government in 1953, it was firmly on the path to independence.

Fairn gave a damning critique of the state of affairs in the colony’s jails. He noted that the prison regime as a whole was based on a system dating from 1892, and its rules from those devised in 1913. More than that, the rules originated in England, in which conditions were quite irrelevant to those of Guiana. What is worst of all, he wrote, is that the rules are so archaic and there are so many of them, that neither staff nor prisoners know what they are or indeed where they are!

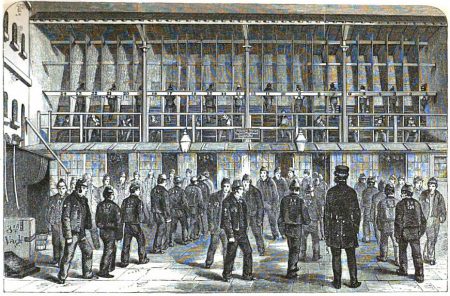

Fairn called for revised and simplified rules, the abolition of penal servitude (work) and hard labour, and the end of the ‘mark system’, a kind of points-based system through which prisoners were not given sentences in time (e.g. of 12 months, or 20 years), but could earn release for good work and behaviour. Rather, he proposed, prisoners should receive remission of sentence in days forfeited by misdemeanour. Fairn noted the limited work opportunities open to inmates, the near non-existence of training, and the mixing of prisoners of all classes (youths, and first and hardened offenders). The food was monotonous, and inmates received no meals between 4.15pm and 6.30am. They were not issued with toothbrushes, combs or pillows. Fairn urged that the role of prisons in any society should be to establish in prisoners the will to lead a good and useful life on discharge, and fit them to do so. This was nowhere in evidence, he claimed, in British Guiana. Ominously, Fairn noted, the extensive wooden buildings of Georgetown jail rendered it a fire risk, particularly because prisoners’ meals were prepared over open fires.

He concluded: The present situation is a daily denial of the standard minimum rules accepted by the Social Defence Section of the United Nations and some attempt must be made to make good the failure. This situation, it must be stressed, had arisen when Guiana was still a British colony.

Questions of prison regulations, alongside those concerning the employment and treatment of prisoners, had long been scrutinised by both colonial officials based in British Guiana and Home Office and Colonial Office administrators in London.

In the late 1820s, the parliament of the United Kingdom requested information concerning the existing conditions of prisons across the British West Indies and commissioners were assigned to establish general prison regulations. British Guiana’s response to parliament’s request showed that local colonial administrators were satisfied with the existing oversight of and conditions in Georgetown’s prison. In fact, during a meeting held by colonial Guiana’s legislative council (the Court of Policy) in July 1830, one member, F P Van Berckel, objected to the idea of making any changes to the system, stating that he did not know how it could be improved. His objection was accepted and the Court of Policy wrote up and published for the first time existing prison regulations. Despite its confidence in the way that things were administered, the issue of prison regulations would be raised repeatedly throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century, and a number of amendments made along the way. One issue was the question of whether regulations created for prisoners in the United Kingdom could be transferred to the Caribbean.

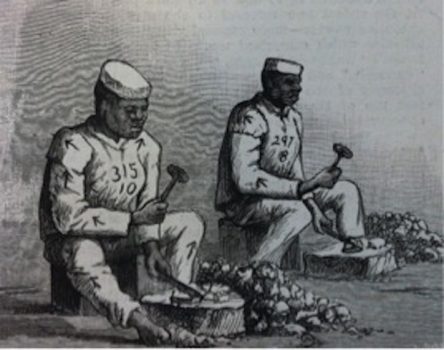

The use of the treadmill was also highly contentious. The jail in George-town was known as a ‘house of correction’ and starting in 1826 the treadmill was one of the forms of punishment used as part of a prisoner’s sentence. The other was breaking stones for use in road building and the construction of the sea wall defences. Within two months of the installation of the treadmill, an enslaved man named Jean Claas (or John Klaas) died in an ‘accident’. It was decided that no one was to blame. Rather his death had occurred ‘through his own violence’. Allegedly, he had refused to be worked on the treadmill and had thrown himself off. In 1840 the governor of the colony, Henry Light, agreed that the treadmill would only be used for ‘refractory prisoners’. This left breaking stones as the main punishment. A decade later the issue was raised again. Indeed, in 1852 the annual prison report stated that the use of the treadmill had been resumed in the previous year.

For the remainder of the nineteenth century, into the 1920s, the colonial authorities were concerned with issues that are familiar to us today. In general, these revolved around how harsh or soft prison conditions should be, and in what ways prisoners could be reformed, rehabilitated and prepared for their release. There were numerous and repeated discussions about whether prisoners should be put to work, what tasks they should perform, what food they should eat, and how they should be punished for offences against jail discipline. The prison also had to deal with drastic changes to the colonial population, following the emancipation of enslaved people in 1838, and the subsequent introduction of indentured labourers from India and China. When they breached labour laws, or committed criminal offences, like formally enslaved and locally born people, they too could be sentenced to jail.

By the 1930s, with the temporary closure of HMPS (His Majesty’s Penal Settlement) at Mazaruni, Georgetown jail became the main prison in the colony. It was a receiving centre for prisoners who were then distributed to other jails throughout the colony. By 1933 the housing of female prisoners in Georgetown had been discontinued, and women were transferred to the New Amsterdam prison. Between 1930 and 1960 Georgetown jail was overpopulated and this continued to be a major problem for administration and security. R D Fairn in his 1956 review described the ‘trebling up’ of prisoners in cells designed for a sole inmate. In the years before Guyana’s independence in 1966, the increasing number of prisoners in the jail placed a strain on its already inadequate accommodation, and made the segregation of prisoners according to age, crime, or sentence almost impossible. Indeed, in 1960 segregation of prisoners at Georgetown Prison was still not in keeping with international standards.

Over the years, the colonial authorities did make efforts to improve the physical conditions under which the convicts dwelt at the Georgetown prison. Seemingly simple improvements included the installation of electric lights, the introduction of water closets, and increases to the size of the cells by combining two cells into one. While these improvements positively impacted the lives and morale of the prisoners, it could still be concluded that, by the time of Guyana’s independence, all the buildings were old, having been built piecemeal, primarily in wood, and as a result had deteriorated, either due to their age, construction or the effects of termites. As well as being a fire a fire hazard, they were unsatisfactory security wise and expensive to maintain.

If the colonial government was unwilling to commit resources to a rebuilding programme, it was obvious that there was a need to make alternative arrangements to deal with overcrowding at Georgetown prison. A recurring suggestion throughout the period was the rebuilding and extension of Mazaruni prison, which was ideally situated, ‘away from the haunts and excitement of the towns’. However, despite some further extensions (notably the building of Sibley Hall, which was initially used for political prisoners), these suggestions were not acted upon. Consequently, the administration made efforts to find a site for the building of a new prison in Georgetown and its environs. There was, however, opposition to the building of the prison near sugar estates and government departments. No way was found to overcome these objections, making compulsory acquisition of the land required the only way forward. In 1958 the superintendent of prisons summed up the issue thus: It is most important that the Georgetown Prison is removed from the centre of the city, apart from the fact the buildings are old they are in urgent need of extensive and costly repairs, are a fire hazard and do not confirm to modern penological conditions, or to even minimum Security standards.

Estherine Adams, Clare Anderson and Kristy Warren have been researching the history of Camp Street Prison, resourced by a Development Research Partnership Grant from the University of Leicester, in collaboration with historians at the University of Guyana. This article draws on materials located in the Walter Rodney Archives in Georgetown, the British Library, and the National Archives in London.