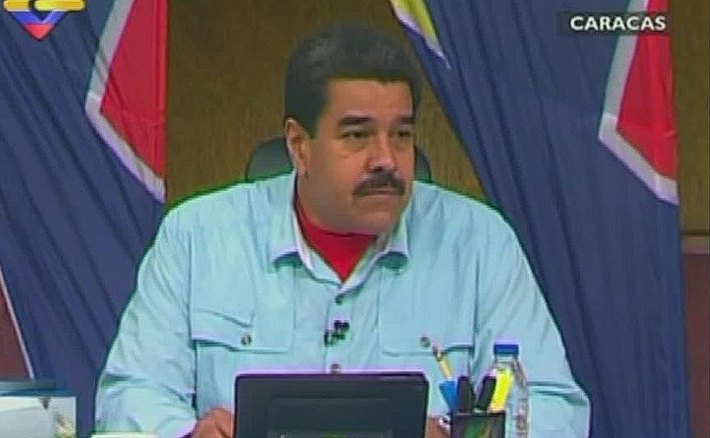

Having established a constituent assembly able to rewrite the Venezuelan constitution, take essential political and economic decisions, and confirm key appointments, President Nicolás Maduro’s government is now moving swiftly to assert its overall authority.

On August 18, the new body effectively nullified the legislative power of elected members of the National Assembly. It did so by giving itself the authority to introduce measures that guarantee “the peace, sovereignty and economic well-being” of Venezuelans. At the same time, the state has begun to move against individuals with alternative credibility, who are being sanctioned or denounced, causing some to flee the country.

On August 18, the new body effectively nullified the legislative power of elected members of the National Assembly. It did so by giving itself the authority to introduce measures that guarantee “the peace, sovereignty and economic well-being” of Venezuelans. At the same time, the state has begun to move against individuals with alternative credibility, who are being sanctioned or denounced, causing some to flee the country.

Meanwhile, a low-key form of ideological struggle is underway within the ruling party to determine the country’s future political model. This will determine whether those in power believe there is a future role for pluralism and an elected opposition of some kind, when presidential and other elections might take place, and establish a much-needed new approach to economic management.

Put another way, seen from the Venezuelans government’s perspective, and from those who have ever studied the theory of revolutions, it may now to be entering a final decisive phase of change.

As this column observed last week, the Caribbean will not be immune from either the short or long-term effects of this or the US reaction. Events in Venezuela are likely to aggravate existing political and economic fault lines in ways that may alter inter-regional and international relations for years to come.

Firstly, change in Venezuela may have geo-strategic ramifications that impinge on Caribbean sovereignty.

If as expected, the Venezuelan economy continues to deteriorate, there is a real possibility that to avoid a debt default, a deal may be struck with the Russian state-linked oil company ROSNEFT. This would see its direct involvement in the country’s oilfield operations, refining and sales, and have the effect of enhancing Russia’s broader economic and military interest in Venezuela and the Caribbean basin.

Although China has a development approach that is different and largely related to maintaining and developing its economic interests and world view, it is likely to welcome and support any measures that result in economic stabilisation.

How the Trump White House might regard both a stronger Russian and Chinese presence in Venezuela is so far unclear. However, some US academics believe that if Russia’s relationship with Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua were to develop significantly, the Caribbean might once again come to be seen in Washington’s eyes, as an ‘arc of concern’, as was the case following the 1979 Grenada revolution.

It is conceivable that some Caribbean nations could benefit from this, if for example significant sums were to be attached to programmes under the US Caribbean Strategic Engagement Act signed into law earlier this year. However, any new form of hemispheric cold war, conditionalities and the resulting polarisation could have uncomfortable inter-regional outcomes if perceived as touching the region’s sovereignty.

Second, the ideological divide in the Caribbean may grow. There are now discernible political differences between nations in the region. While much of the US media portray this as a simple reflection of purchased obligations through PetroCaribe or of states’ membership of the Bolivarian Alliance (Alba), it is apparent that the positions being taken reflect genuinely differing political philosophies.

These for example place St Vincent, Dominica and Cuba on one side, and politically conservative governing parties in nations including Jamaica, St Lucia and Barbados on another, with each in private expressing concerns that pass beyond the humanitarian.

This raises a more potent long-term question about the coherence of future inter-regional decision-making on matters from foreign policy to economic relations.

As is already the case, Heads of Government meetings have been disrupted over Venezuela and issues that have ideological rather than a pragmatic context. If linked to existing inter-regional reservations about Caricom, or subject to external pressure, this would seem at best likely to make collective decision-making ever more complex.

Thirdly, refugee flows may change popular perception. Refugee numbers are increasing and could surge because of new US sanctions. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees says there are around 40,000 Venezuelans now in Trinidad and Tobago. There are also large numbers in the Dutch Antilles, and Dominican Republic statistics recently suggested that some 35,000 Venezuelans are now there. The implication is that should the internal situation in Venezuela deteriorate, refugee numbers and migration could for Cariforum’s less advantaged citizens become a potent and destabilising domestic political issue.

Fourth, it is likely that the situation in Venezuela and external reaction could result in hard choices. While Mexico is considering the possibility of developing a programme of its own to replace PetroCaribe, this is far from certain. In the absence of any alterative, providence suggests that Caribbean governments still dependent on the facility, heavily indebted to it, or holding out for promised investments, ought, as Cuba has done, address rapidly the budgetary and supply implications.

Space does not permit much more, but it is also likely that present problems may make the border controversy with Guyana harder to resolve; and the Caribbean an unlikely partner for mediation with the opposition in Venezuela, not least because recent actions by the Maduro government suggest that moment may have passed.

Although it may not be popular to say so, barring a military coup or some other form of uprising, the Venezuelan government may now be able to consolidate its political position, resist and fragment hemispheric and international criticism, and gradually resuscitate its oil and gas industry to take advantage of the fact that with better management it is ultimately energy rich.

This is not to deny the humanitarian crisis or the present unpopularity of the Maduro government with many Venezuelans, but to suggest it will survive, and that as with Cuba in the 1960s a new normal could emerge.

If this is correct, it suggests Caricom governments given their limited resources ought to be trying to find an accommodation that addresses their short-term concerns while retaining a high degree of neutrality. In the past, the Anglophone part of the region had politicians who were adept at doing this. It is far from clear, however, whether such skills any longer exist.

Previous columns can be found at www.caribbean-council.org