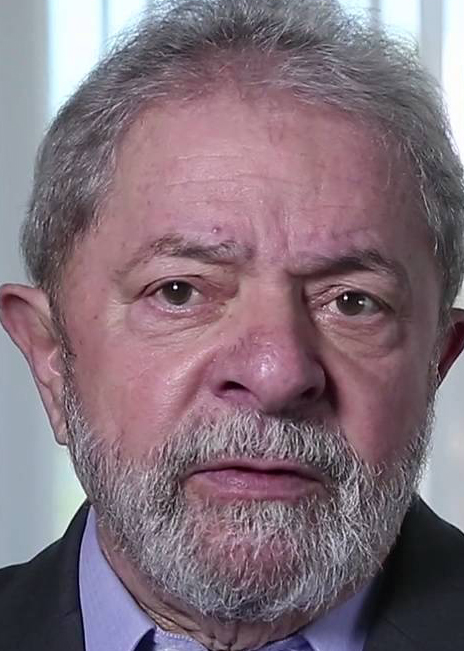

MACEIÓ, Brazil (Reuters) – Thousands have turned out to see leftist former president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva on his marathon bus tour of impoverished northeast states, the region where Brazil’s first working-class leader was born and where he has maintained the most support.

Rural workers whose lives improved dramatically with Lula’s social programmes swarmed his bus at every stop to greet the union leader born of an illiterate mother. Some, weeping, reached out to touch him as if he were a demigod.

The three-week tour is an unofficial launch of a possible campaign for next year’s presidential elections.

A prolonged economic crisis and corruption scandals that have engulfed President Michel Temer and much of Brazil’s political class, including Lula, rekindled the ever-popular veteran politician’s hopes for returning to power.

Yet even as support for a Lula comeback has pushed him to the top of early election surveys, thanks to nostalgia for the commodities-based economic boom he presided over, the rate at which voters reject the divisive leader looks too high for him to win, said Mauro Paulino, the director of the respected Datafolha polling group.

And there is a more serious hurdle.

Lula faces the likelihood of being barred from running if a conviction on corruption charges handed down by a federal judge last month is upheld on appeal.

Lula acknowledged in an exclusive interview with Reuters this week that his Workers Party must be ready to field another candidate, a prospect welcomed by investors who see a 2018 race without him improving the chances of Brazil sticking to fiscal austerity pursued by Temer.

“Obviously, if you look at the current scenario, I am the most important figure to lead the Workers Party campaign. But we have to accept that in politics, things happen that are out of our control,” Lula said, referring to his conviction for accepting bribes that could land him prison.

Political vacuum

Under Brazilian law, a politician is barred from participating in politics for at least eight years if they are convicted of a crime and it is upheld on appeal.

Lula faces another five trials on corruption charges, but only his July conviction is likely to have been weighed by an appeals court before next October’s election.

While there is some disagreement among legal experts, the consensus is that if he is convicted and it is upheld on appeal after he runs for and potentially wins the election, Lula would be protected and retain immunity from jail time for as long as he were to remain president.

A Datafolha poll taken in late June showed Lula’s popularity steady at 30 per cent in a first-round vote, double his closest potential competitors.

But in a likely second-round runoff, the poll found Lula in a technical tie with his former environment minister, Marina Silva, a two-time losing presidential contender.

“There is a political vacuum in Brazil since the corruption investigations brought charges against other politicians, even President Temer,” said the pollster Paulino. “That reinforced the view of Brazilians that corruption went well beyond Lula and the Workers Party, and increased support for his return.”

The proportion of Brazilians who say they would never vote for Lula has dropped over the past few months to 46 per cent in July, down from 53 per cent in April and 57 per cent in March, according to polls by Datafolha.

But that rate of rejection is still too high to win a presidential runoff and it is likely to rise, since Datafolha has not conducted a survey since Lula’s conviction and a nearly 10-year prison sentence were announced.

Plan B

Brazilians are eager to find new leaders untarnished by their country’s largest-ever corruption scandal. Fresh names such as Sao Paulo mayor Joao Doria, a millionaire who won by landslide last year, are emerging as possible candidates for 2018.

In such a context, the Workers Party would be better off fielding a less polarizing candidate than Lula, such as the former Sao Paulo mayor Fernando Haddad, who was easily defeated by Doria last year, said Adriano Oliveira, a political scientist at the Federal University of Pernambuco.

Haddad would take just 3 per cent of potential first-round votes, according to a late-June Datafolha poll.

Despite that, Oliveira said, Brazil’s lower-middle and working classes are looking to the Workers Party as the main opponent of Temer’s unpopular belt-tightening reforms to labour laws, his efforts to lessen generous pensions and aggressive privatizations of state-held enterprises.

“Lula is not the party’s best option because his candidacy would lead to a very aggressive campaign,” Oliveira said. “Haddad faces little rejection and would benefit from the resurgence of Lulismo.”