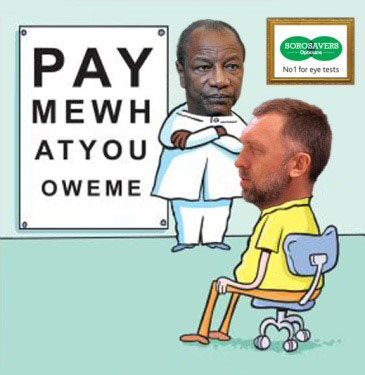

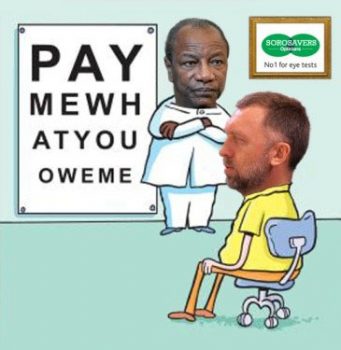

On reading last week that a decade after the dispute arose between Rusal, the Russian bauxite company, and the Guyana Bauxite and General Workers Union (GBGWU), union officials still had to be forcing their way into government offices to demand that their long-standing grievances be properly considered, I remembered the cartoon above, which portrays a confrontation between Mr. Oleg Deripaska, president of Rusal, and Alpha Conde the first democratically elected president of Guinea.

Without commenting upon the merits of the case on either side, in the normal course of such events, this dispute should not have lasted this long as there are legal and institutional mechanisms in Guyana for its resolution. Industrial disputes are inevitable, but there exist, for example, the Labour Act, the Trade Union Recognition Act, the Termination of Employment and Severance Pay Act, and a Labour Department that, independently or when requested by the parties, must seize and take a dispute through the various stages of mediation, conciliation and, if necessary, arbitration. Comparatively rarely, matters go to court, but the expectation is that decision and necessary action arising therefrom will be timely. This has clearly not happened in this case and suggests the absence of political will to properly deal with the interest of the working people and since multinational companies tend to act similarly, vigilance is necessary in our relationship with the global giant Exxon Mobil. That said, the big questions are why this dearth of political will and what is to be done?

So far as I am concerned, that the PPP/C did little to solve the dispute is quite understandable, even if pernicious. Convinced that it was being deliberately obstructed in its democratic/majoritarian right to govern, instead of properly coming to grip with is ethnic context and choosing the more sensible path of sharing government, the PPP set about dismantling the institutions of those it considered its foes, i.e. those of PNC/African ethnicity, and entrenching itself in government essentially based on its ethnic majority. In this context, it was not interested in solving issues that would have impacted positively on an African dominated union. As we shall see below, the absence of a strong political will to support the union fed into the general modus operandi of Rusal.

So far as I am concerned, that the PPP/C did little to solve the dispute is quite understandable, even if pernicious. Convinced that it was being deliberately obstructed in its democratic/majoritarian right to govern, instead of properly coming to grip with is ethnic context and choosing the more sensible path of sharing government, the PPP set about dismantling the institutions of those it considered its foes, i.e. those of PNC/African ethnicity, and entrenching itself in government essentially based on its ethnic majority. In this context, it was not interested in solving issues that would have impacted positively on an African dominated union. As we shall see below, the absence of a strong political will to support the union fed into the general modus operandi of Rusal.

Guinea is the fourth highest producer with the largest bauxite reserve in the world and Rusal and other multinationals e.g. Alcoa and Rio Tinto, have interests there and Rusal’s website seeks to present it as a paragon of social responsibility. However, a government review of the mining agreements it made with the previous dictatorial regimes found that Rusal had paid well below the real value for its assets at privatization in 2006, had failed to pay for required environmental clean-ups, induced government officials to act illegally and unilaterally halted operation and locked out the workers in 2012. The company was apparently required to renegotiate the terms of its agreement and to pay compensation of some US$1 billion (http://johnhelmer.net/rusal-negotiations-fail-in-guinea-once-again-conakrys-bill-is-more-than-1-billion/).

Guinea is the fourth highest producer with the largest bauxite reserve in the world and Rusal and other multinationals e.g. Alcoa and Rio Tinto, have interests there and Rusal’s website seeks to present it as a paragon of social responsibility. However, a government review of the mining agreements it made with the previous dictatorial regimes found that Rusal had paid well below the real value for its assets at privatization in 2006, had failed to pay for required environmental clean-ups, induced government officials to act illegally and unilaterally halted operation and locked out the workers in 2012. The company was apparently required to renegotiate the terms of its agreement and to pay compensation of some US$1 billion (http://johnhelmer.net/rusal-negotiations-fail-in-guinea-once-again-conakrys-bill-is-more-than-1-billion/).

So far as the locked-out workers were concerned, it was reported that in 2011, claiming difficult economic conditions, Rusal’s management refused to engage in collective bargaining with the union and aggressively followed a tactic of intimidation and provocation. In the first quarter of 2012, the workers struck in protest at management intransigence and the latter immediately suspended its operations, locking out some 1,030 permanent employees and 2,000 outsourced workers without pay. Rusal was also accused of pressuring the local labour court to declare the strike illegal, and although at government-arbitrated negotiations the workers agreed to lift the strike, the company refused to end the lockout until the unions accepted responsibility for company losses during the strike, obviously the union refused to do so (http://www.industriall-union.org/the-drama-of-rusal-friguia-workers-in-guinea).

On coming to government, Conde, with former British Prime Minister Tony Blair and global investor George Soros as his good governance advisors, claimed that he would make Guinea a laboratory of global transparency in the oil and mining industries and reportedly at one point ordered Deripaska out of his office. However, ominously, by 2016 Conde was being accused of election rigging and collaboration in taking a US$10.5 million bribe from Rio Tinto. The company confessed to making the payment but the president denied any association with the deal (http://www.riotinto.com/media/media-releases-237_20002.aspx). .

I would have wagered that if the PNC were ever to come to government ending the dispute between the GBGWU and Rusal would have been one of its earliest priorities. After all, although its political commitment can be quite volatile, Linden has historically been one of staunchest constituencies of the PNC and contributed significantly to the coalition being in government today. For example, in 2001 the PNC received 14,027 out of a possible 21,903 votes from Linden. In 2006, this was reduced to 7,369 out of 13,755 but in 2011 rose to 11,358 out of 15,585 and 16,791 out of 19,742 in 2015. In the normal scheme of democratic electioneering, what occurred in 2006 should have propelled the regime to act quickly, but alas this was not to be!

In 2015, the PPP/C lost government and a year later the new administration reinstated the workers’ over-time tax-free concessions, which they apparently are yet to receive because of the dispute and ministers began to make serious noises about conditions at the company’s operations. However, when the company was invited to the Ministry of Social Protection for a meeting on 15 November 2016 to discuss the dispute, it failed to show up and set about establishing its own internal mechanism for management/worker cooperation. Ministers furiously accused Rusal of insulting the laws and government of Guyana, but in the absence of strong political will, nothing significant has changed.

In about 1993, well before the passing of the Trade Union Recognition Bill, Cheddi Jagan, on a trip to its interior site, made it quite clear to a general meeting of the management and workers that trade recognition was non-negotiable. However, on 18 November 2016, nearly a decade after the Rusal dispute began, asked at his public interest media discussion whether it was not time that cease and desist orders be issued against Rusal, the president urged the Ministry of Social Protection to remain engaged with the company despite the fact that the company had clearly shown no intention of wanting to seriously engage with it. ‘I don’t think we need to reach the level of a cease order at this point in time. There are measures which could be put in place by the unions to ensure that the controversies are adjudicated and I do not think those measures have been exhausted at this point in time’, the president claimed.

The reader might have the answers but it is difficult for me to fathom why the PNC, which has the time to dally with establishing parking meters in Georgetown, believes it can play so fast and loose with the rules and treat a core but still volatile constituency with such contempt. Partly it rightly assesses that its constituency does not believe that it has a viable political option. However, it should remember that in 2015, if only by the narrowest of margins which suggest that ethnic alliances are still too strong, the PPP/C paid the usual political price in a democracy for such cockiness.

The immediate question, therefore, is what, if anything can be done to weaken the expression and consequences of ethnic voting and induce greater compliance with the rules. I still believe that the answer lies in radical constitutional change that introduces a more equitable and participative governance arrangement (‘Why I support APNU:’ SN16/11/2011).