LIMA, (Thomson Reuters Foundation) – Wedged between the rubbish-choked Rimac river and lanes of traffic belching fumes, the Cantagallo slum in downtown Lima is a far cry from the Amazon rainforest land that the Shipibo-Konibo people were forced to flee two decades ago.

Hundreds of families belonging to the Peruvian indigenous group make their home in this gritty wasteland just a few blocks from the capital’s main square.

Forced from their homes by violent leftist Shining Path rebels or pushed out by extreme poverty and lack of opportunities, the Shipibo-Konibo now face fresh problems in the new settlement.

This time they are fighting back, trying to win secure titles to their land and improve their living conditions, yet deeply mistrusting each other and the authorities tasked with helping them.

A massive fire last year destroyed more than 400 of the Shipibo-Konibo’s makeshift homes, many made from wood and tarpaulin, sprawled along the city hilltop.

Lima Mayor Luis Castaneda promised in April to rebuild the burned-out homes on the same spot and says local authorities will provide about $150 a month to each family to subsidise temporary accommodation in the meantime.

Vladimir Inuma represents some of the Shipibo-Konibo families in Lima and is fighting for guarantees from the mayor’s office that the proposed plans will be enacted.

With about 20,000 people, the Shipibo-Konibo is one of the country’s largest Amazon tribes. About 2,000 of them live in the Peruvian capital.

Inuma told the Thomson Reuters Foundation that the Shipibo-Konibo is splintered, and tribal leaders do not agree on how to proceed. He also said the tribe has been “tricked” once before, when a plan to relocate the community was mothballed in favor of building a bypass.

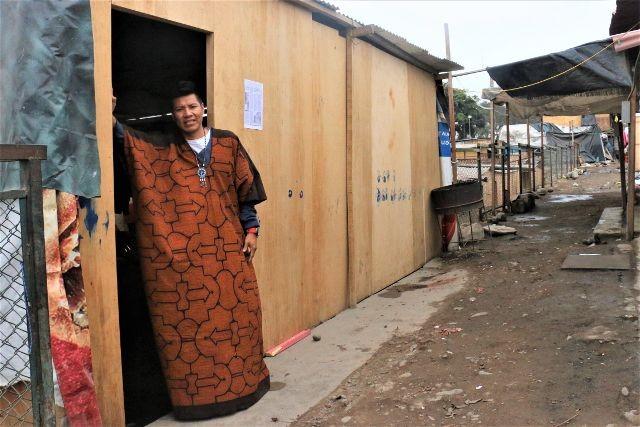

“We have been very distrustful of the other leaders. They have been colluding with Lima council,” he said outside his house of wood and plastic.

Inuma and most of the Shipibo-Konibo in Lima have agreed to leave temporarily so the Cantagallo slum can be rebuilt as promised.

But a few are insisting upon staying out of fear that they could be left homeless if they leave. Some families have moved onto a patch of wasteland at the edge of the site to keep a watchful eye, and others have moved into apartments but return to Cantagallo each night to sleep.

“Up to now, nothing has been finalized,” said Cesar Maynas, another representative for the families.

CANTAGALLO IS EMBLEMATIC

Peru’s indigenous groups, which make up roughly 45 percent of its population of 31 million people, often lack secure property rights and access to basic services such as health care and education, local rights groups say.

“The situation in Cantagallo is emblematic because it’s only ten minutes away from the presidential palace,” said Mar Perez, head of economic and social rights at the National Coordinator for Human Rights.

“They’ve been living in Lima for 20 years, and until now they haven’t even been able to formalise their land titles or gain access to basic services,” Perez said.

The issue of housing and land titles is common across South America, where mass migration to urban areas has led to some 113 million people – or nearly one in five people – living in slums.

The conditions fuel inequality, social exclusion and conflict between landless communities and government authorities, experts say.

Without formal property deeds, residents are at risk of eviction to make way for private or government-backed development projects.

Rights groups say local authorities in Lima are reluctant to grant land titles to the Shipibo-Konibo because they fear it could set a precedent for other groups living in informal settlements, often seen as land invaders and illegal squatters.

Ebert Lozano, who leads the Cantagallo reconstruction project at the mayor’s office,said $610,000 has been set aside to subsidise rent for families until building is complete in late 2018.

“We are supporting them so that they can have somewhere to live while reconstruction takes place. When the project is finished, they will come back and their houses will be built,” Lozano told the Foundation.

In the aftermath of the fire, Peruvian president Pablo Kuczynski visited Cantagallo and promised to rehouse the community on the current site.

Lozano said the reconstruction project aims to build 231 houses, new roads, a park and landscaped green spaces.

“It’s going to be a beautiful place,” Lozano said, adding that the new houses would have access to water and electricity.

Despite such promises, Cantagallo residents remain wary.

Rosa Pinedo, 27, said that she has little confidence that the mayor will follow through on his promises.