RIYADH, (Reuters) – All major Gulf stock markets slid yesterday on jitters about Saudi Arabia’s sweeping anti-graft purge, a campaign seen by critics as a populist power grab but by ordinary Saudis as an overdue attack on the sleaze of a moneyed ultra-elite.

U.S. President Donald Trump endorsed the crackdown, saying some of those arrested have been “milking” Saudi Arabia for years, but some Western officials expressed unease about the possible reaction in Riyadh’s opaque tribal and royal politics.

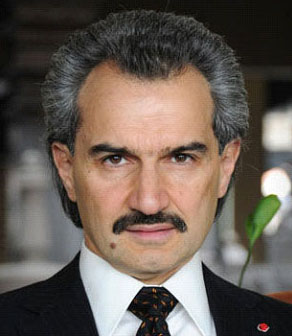

Authorities detained dozens of top Saudis including billionaire Prince Alwaleed bin Talal in a move widely seen as an attempt by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman to neuter any opposition to his lightening ascent to the pinnacle of power.

Admirers see it as an assault on the endemic theft of public funds in the world’s top oil exporter, an absolute monarchy where the state and the ruling family are intertwined.

“Corruption should have been fought a long time ago, because it’s corruption that delays society’s development,” Riyadh resident Hussein al-Dosari told Reuters.

“God willing, everything that happened … is only the beginning of what is planned,” said Faisal bin Ali, adding he wanted to see “correcting mistakes, correcting ministries and correcting any injustices against the general population.”

But some analysts see the arrests as the latest in a string of moves shifting power from a consensus-based system dispersing authority among the ruling Al Saud to a governing structure centred around 32-year-old Prince Mohammed himself.

Investors worry that his campaign against corruption – involving the arrests of the kingdom’s most internationally known businessmen – could see the ownership of businesses and assets become vulnerable to unpredictable policy shifts.

Saudi banks have frozen more than 1,200 accounts belonging to individuals and companies in the kingdom and the number keeps rising, bankers and lawyers said.

The authorities sought to reassure the business community late on Tuesday, with the central bank saying it was freezing suspects’ personal bank accounts at the request of the attorney general but not suspending operations of their companies.

“In other words, corporate businesses remain unaffected. It is business as usual for both banks and corporates,” the bank said in a statement, adding there were no restrictions on money transfers through proper banking channels.

A separate statement said Prince Mohammed had directed a powerful ministerial committee, the Council for Economic Affairs and Development, to ensure that national and multinational companies, including those wholly or partly owned by individuals under investigation, were not disrupted.

“The Council recognised the importance of these companies for the national economy, and the importance of ensuring that investors could operate with confidence in Saudi Arabia,” the state news agency SPA said.

In Washington, Heather Nauert, spokeswoman for the U.S. State Department, said it had urged Saudi Arabia to undertake any prosecutions of corruption suspects in a “fair and transparent” manner.

She said the United States had received assurances from the Saudi government that it would do so. But another U.S. official later told reporters she had misspoken and that they had no such assurances that they could discuss in public.

The Saudi stock index .TASI sank 0.7 percent in heavy trade, led by shares in companies linked to people detained in the investigation.

The market, which was down 3.1 percent at one stage, would have finished much lower without apparent buying by government-linked funds seeking to prevent a panic, fund managers said. A mass pull-out of foreign funds was not apparent.

Among the companies, Prince Alwaleed’s Kingdom Holding plunged by its 10 percent daily limit, bringing its losses in the three days since the investigation was announced to 21 percent. The fall has wiped about $2 billion off his fortune, previously estimated by Forbes magazine at $17 billion.

In Dubai, where Saudis have been significant investors, the index slipped 1.8 percent. The index in Abu Dhabi , less exposed to Saudi money, fell only 0.4 percent. But Kuwait continued to slide, its index losing 2.8 percent.

The show of investor nerves coincided with sharply heightened strains between Riyadh and Tehran, reflected in a fresh denunciation of adversary Iran by Prince Mohammed over its role in Yemen, and by continuing mutual acrimony over political turmoil in Lebanon, another cockpit of Iranian-Saudi rivalry.

Displaying an apparently undimmed taste for navigating several challenges simultaneously, Prince Mohammed said Iran’s supply of rockets to militias in Yemen is an act of “direct military aggression” that could be an act of war.

He was speaking in a phone call with the British foreign minister after Saudi forces intercepted a ballistic missile they said was fired towards Riyadh on Saturday by the Houthis.

A Saudi-led coalition, which backs Yemen’s internationally-recognised government, has been targeting the Houthis in a war which has killed more than 10,000 people and triggered a humanitarian disaster in one of the region’s poorest countries.

Iran has denied it was behind the missile launch, rejecting the Saudi and U.S. statements condemning Tehran as “destructive and provocative” and “slanders”.

The coincidence of heightened Saudi-Iranian tensions and Saudi domestic political upheaval has stirred unease among some Western governments and analysts about the emergence of an impromptu policy-making style under Prince Mohammed and turmoil in a region traditionally seen as a haven of stability.

“He seems to be pushing the creation of a personalised system of rule without the checks and balances that have typically characterised the Saudi system of governance,” wrote Marc Lynch, professor of political science and international affairs at George Washington University, in the Washington Post.

“In both domestic and foreign affairs, he has consistently undertaken sudden and wide-ranging campaigns for unclear reasons which shatter prevailing norms.”

Among those held in the anti-graft purge was Prince Miteb bin Abdullah, who was replaced as minister of the National Guard, a pivotal power base rooted in the kingdom’s tribes. That recalled a palace coup in June that ousted Mohammed bin Nayef, known as MbN, as heir to the throne.

MbN made his first confirmed public appearance since then at the funeral for Prince Mansour bin Muqrin, deputy governor of Asir province, who was killed in a helicopter crash on Sunday. No cause has been given for the crash.

A photo shared online by a state media photographer showed MbN greeting another royal at the first major family gathering since the anti-corruption sweep began.

The crackdown removed any remaining political counterweights to the crown prince, according to Steffen Hertog, a Saudi scholar at the London School of Economics.

“This allows for fast decision-making and reduces costly involvement of princes in state contracts, but also potentially reduces internal criticism and review of new policy initiatives,” he said.

A former senior U.S. intelligence official cautioned that given the National Guard’s loyalties, Prince Mohammed could face a backlash. “I find it difficult to believe that it (National Guard) will simply roll over and accept the imposition of new leadership in such an arbitrary fashion,” he said.

But the purge may go some way to soothing public disgust over financial abuses by the powerful, some Saudis say.

“There is no doubt that it (the detentions) soothes the anger of the regular citizen who felt that such names and senior leaders who appeared in the list were immune from legal accountability,” said Saudi-based political analyst Mansour al-Ameer.

“Its spread to the general population is evidence that no one is excluded from legal accountability, and this will eventually benefit the citizen and (national) development.”