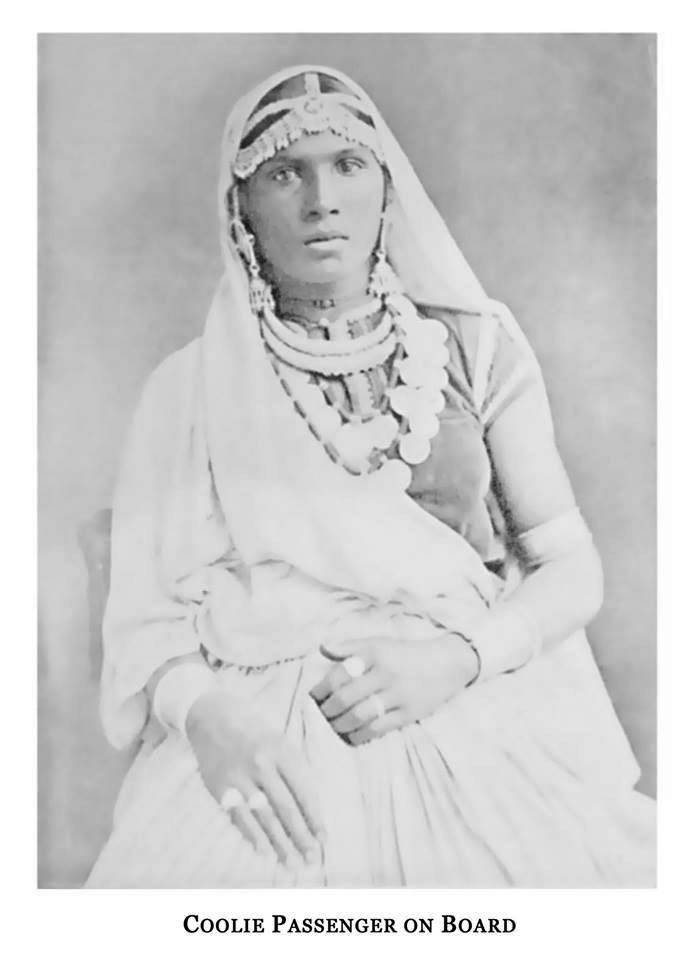

Her expressive eyes are deep and dark, a certain painful poignancy to them as she stares, so serious, straight into the camera, le aning slightly, with full lips slightly open. Rings adorn slender fingers on both hands and long “jhumka” earrings with their characteristic fringed bell shapes reach the top of covered shoulders.

aning slightly, with full lips slightly open. Rings adorn slender fingers on both hands and long “jhumka” earrings with their characteristic fringed bell shapes reach the top of covered shoulders.

Several chains in graduated sizes ranging from the simple necklet with a sacred single “rudraksha” protective bead, to a pair of solid silver torques in the tribal style decorate her dress of draped sari pleats, slung into a loose “orhini” or head covering.

Since the old image is in black and white, we cannot tell if the elaborate beaded “tikka” ornament arranged across her forehead and parted hair, may be a “mathapatti” or South Indian wedding band with the characteristic gold, red and green that could have been echoed in the fine, braid-embellished coloured velvet “choli” or blouse.

Matching “churias” or broad bracelets and a smaller armlet are visible. But the most prominent pieces of jewellery are the two-tiers of necklaces lined with about 30 large coins. We only know the mysterious beauty as the “Queen of Sheba” after the unlikely title conferred on her by the British sea captain, W.H.Angel and crew in 1877, while on their way to the holding depots at Five Islands, Trinidad, and later Demerara, British Guiana.

In his 1921 memoir of life aboard “The Clipper Ship ‘Sheila’” launched to fast ferry thousands of indentured labourers to British colonies, the skipper refers to her and the some 600 Indians aboard the vessel’s first such famous voyage to the West Indies, using the now offensive but then common term for Asian workers paid low wages.

“Amongst our coolie passengers (she paid her own passage money down), was a fine looking woman about forty years of age. She had returned to India from Trinidad, having completed her term entitling her to a free passage. She got the name among us of the ‘Queen of Sheba.’ She had made quite a considerable fortune in the island, partly by judicious marriages, and partly in her widowhoods, and as a trader, for as such she had a natural inclination.”

Captain Angel added, “in time a longing came over her to return to the land of her birth, but a short experience was enough for her. The priests got hold of her, and required her to do heavy penance, and pay a lot of money to get back her caste, which she had lost by leaving India; but she declined to buy the goods at the price asked, and came with us again, her expression and verdict on the subject being: ‘India only fit place for coolie.’ ”

A remarkable, free woman with the monetary means and a mind of her own, courageous enough to independently undertake her third crossing of the dreaded “kala pani” or black waters, she stepped confidently between worlds, on to the tiny volcanic “little dot of an island” and British Overseas Territory that was the remote first stopover in the South Atlantic Ocean, famed as the final prison of the French statesman and military leader, Napoleon Bonaparte.

Despite the Captain’s claim that the human cargo had grown “quite fat and sleek,” he acknowledged that “she made a corner in fresh fish at (Jamestown, the capital) St. Helena by buying up all the fishermen’s catch for the day, as a treat for the coolies on board,” making an unusual reference to this noticeable but still anonymous passenger who shows empathy for her fellow migrants. Angel never bothers to ascertain or reveal her real name.

“The lady was a sight to look at when she was fully dressed, according to her ideas. For one thing she was loaded with jewellery all over her person — immensely heavy silver bracelets from the elbows to the shoulder, also from the wrists to the elbows on both arms; similar from ankles to knees; a kind of diadem on the forehead; a lot of rings of all sorts on her toes and her fingers; a pendant nose ring; and the ear-lobes were pierced with holes big enough to admit bottle corks, which were the customary adornment at ordinary times, but in cases of ceremony, the holes were decorated in the same manner as the rest of her person.”

He continues, “Of course, I have not described the rest of her wearing apparel, but I believe she did have some on — must have had, or I should have noticed the deficiency; but being a mere man I must plead inability to describe the intricacies of ladies’ apparel. Anyhow, you may depend on it, she was in the height of fashion.”

Yet the enigmatic image that is immortalised in Angel’s account is of a lovely young woman with a fresh, unlined face certainly far under 40 years old, lacking the nose ring normally worn on the left by married females, which may have been removed a sign of respect or an acknowledgment of her reported widowed status.

How and when the photograph was taken is unknown. It is possible that given her visible wealth and experience, she may have had it recorded earlier, as a personal memento of her material achievements, before leaving Trinidad or India. Regarded as a popular mark of beauty and social standing, the nose stud or “phul” and the ring or “nath” are a symbolic traditional adornment in tribute to Maha Parvati, the Hindu mother goddess of marriage, love, fertility and devotion, who is the model wife and powerful partner of Lord Shiva, the great destroyer and transformer.

Workers like “Sheba” had to complete at least a decade of indentureship which indicates that she may have originally landed in Trinidad during the early 1860s. According to Angel, this bond really meant an average 14 years after which the recruits were entitled to a paid return to India.

“That was absolutely at their discretion, or they could claim their passage money back, or take a free grant of ten acres of crownlands, and become free to do as they liked. Some took the cash, and went to various occupations, many becoming highly prosperous and rich. In their places of origin in the agricultural districts of India their pay only averaged from one to three annas a day (that is in English equivalent, three half-pence to four pence halfpenny per day) and feed themselves; in the West Indies, when on the estates, their pay commenced at twelve pence half penny per day and all found, for the first two years — after which their emoluments rose much higher on a sliding scale — and they were also provided with free quarters, doctor, and hospital.”

He decried that their wages were “paid to them in English silver coins, which they promptly put out of circulation by melting them into personal ornaments of all kinds,” such as in “the rig-out of the ‘Queen of Sheba.’”

“It is one of the grievances of the government that owing to this they have constantly to import silver coins to keep pace with the loss; and some of the wealthier class of coolies go even one better by melting down the gold coinage, and turning it into elaborate heavy rings set with valuable stones,” he complained.

Considered sacred metals in Indian culture, gold represents renewal, the shining sun and the spiritual cosmos, with the purest form associated with eternal life, since in 24 carat it does not oxidise or corrode. The cheaper sister metal silver suggests the complementary moon and is common in tribal wear.

Remarking that his passengers “differed greatly in colour, varying from black to light brunettes,” Angel thought, “their features, as a rule, were most pleasing, and amongst them were some beautiful girls, with long, straight and abundant hair.” However given the “illusiveness” of their features he could not recognise one half of them.

A few immigrants had died from stomach complaints but “Sheba” was among the 420 men, 128 men, and 84 children including newborns, who survived the September 1 journey from Calcutta, eventually landing in Trinidad on November 17, 1877. Angel noted, “we were all complimented on their fine condition by the authorities.”

“On leaving, my crew awoke the echoes by giving them no end of cheers, and several rousing shanties. The coolies, at the start of the voyage could not make out what that kind of singing meant, it being so strange to their ears; but towards the end, it was amusing to hear their attempts to join in. They never accomplished it.”

As they passed, “they all put their hands to their foreheads, bowed low, and said: ‘Salaam, burrah Sahib.’”

ID is still to read William Black’s novel, “A Princess of Thule.” The “Sheila” was christened in the River Clyde as the “most expensive” and fastest clipper made of Gartsherrie iron and named for the Scottish writer’s romantic heroine.