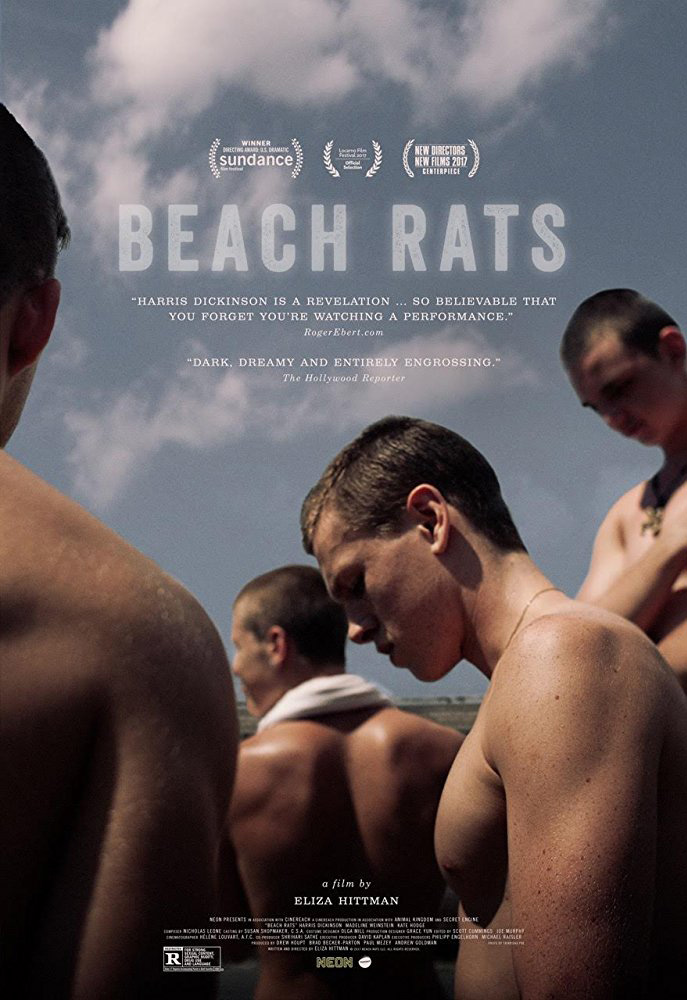

“Beach Rats,” the winner of the best director award at this year’s Sundance film festival, is a filmic bildungsroman. It sets out to trace, in general terms, a formative experience for its protagonist. But it’s not really a coming-of-age film, as one would expect. Instead, “Beach Rats” turns this tale of a teenage journey of sexual self-discovery into a horror film. The overwhelming mood of horror does not come from specific scenes, particularly. In fact, the film does not have anything resembling a true a jump-scare until the last 20 minutes, which are incidentally the worst of the film. But the preceding 70 minutes feature moment upon moment that pulsates with dread, that teases disaster and that leans into the uncomfortable. This film wants us to feel dread. From the opening shots of a boy in his bedroom, it promises doom, it promises desolation and it promises tragedy. It makes good on all promises.

It makes for an odd mood for an LGBT film in a post-“Moonlight” world. “Moonlight,” the 2016 Oscar winner for Best Picture, stands high as the first emphatically gay Best Picture winner, as against the ambiguously gay “Midnight Cowboy.” Its place in history casts a long shadow over any other pseudo-coming-of-age LGBT drama which comes immediately after. “Beach Rats,” like the upcoming LGBT drama “Call Me By Your Name,” has been dismissed as the White “Moonlight.” Ungenerously so. Despite the “Moonlight” associations, “Beach Rats” is more in tune with a previous Black coming of age film, Dee Rees’ “Pariah,” a singular tale of a black girl’s journey to discovering her sexuality. Both films live in their isolation. To be gay in the 21st century is not an ‘It Gets Better’ narrative but one that roots you in separation. It’s a discomfiting thesis, but one that ‘Beach Rats’ never wavers on delivering.

It makes for an odd mood for an LGBT film in a post-“Moonlight” world. “Moonlight,” the 2016 Oscar winner for Best Picture, stands high as the first emphatically gay Best Picture winner, as against the ambiguously gay “Midnight Cowboy.” Its place in history casts a long shadow over any other pseudo-coming-of-age LGBT drama which comes immediately after. “Beach Rats,” like the upcoming LGBT drama “Call Me By Your Name,” has been dismissed as the White “Moonlight.” Ungenerously so. Despite the “Moonlight” associations, “Beach Rats” is more in tune with a previous Black coming of age film, Dee Rees’ “Pariah,” a singular tale of a black girl’s journey to discovering her sexuality. Both films live in their isolation. To be gay in the 21st century is not an ‘It Gets Better’ narrative but one that roots you in separation. It’s a discomfiting thesis, but one that ‘Beach Rats’ never wavers on delivering.

Frankie is a teenager in Brooklyn, as poor as he is White. His father is dying of cancer, his mother is affable if frustrated as she survives on a diet of coffee and cigarettes, and his pre-teen sister is equal turns baffled and unnerved by him. Frankie is directionless. So much so that another name for the film might have been Loafers. Frankie and his three friends skulk on the boardwalk engaging in petty thievery (a quick early scene of pickpocket does well to establish indecision as a key character trait), and smoke weed. It’s a generic life. Cripplingly so. He falls into a casual relationship with a girl as that does bring the excitement they both wish it could. Amidst this, Frankie is living somewhere deep, deep in the closet. He frequents online hook-up sites, where he engages in the most uncomfortable of sexual encounters. It’s a sad world, and one the film keeps its camera on, unrelentingly.

“Beach Rats,” which was also nominated for its cinematography, is bathed in a dull hue that suggests the inchoate. As a piece of queer cinema, it, perhaps, does not offer much that is new. Frankie’s internalised tinge of homophobia perhaps is more potent in 2017 that’s been surreal for its revelations of the private lives of homophobes in the public sphere. But it’s not so much that he hates his gayness as he is cripplingly embarrassed by it. The film’s “It Doesn’t Get Better” counter-thesis can be seen a mile away before the ending but it points to a particular tenor of lower class unrest that might be too often romanticised on screen. LGBT films tend to make use of characters’ awareness and acceptance of their sexuality as a liberating motif, but “Beach Rats” eschews this focus, for obvious reasons. Even the worst of LGBT films is fulfilling a sort of didactic purpose, reaching out to teenagers who are in the same situation. For a film, like “Beach Rats” to so mulishly argue that things are awful now, and will be awful in the future, is troubling. The film received some ire from the LGBT community when it premiered at Sundance.

Writer-director Eliza Hittman, a straight woman, seems just as invested in the socioeconomic dilemma as the cultural sexual one, though. It’s not that Frankie’s gayness traps him, but his social class definitely does. Her oversexualizing of Frankie’s body is more unsettling than erotic. Whenever Frankie gets online on the hook-ups sites like chatrooms of the old internet age, his potential conquests keep telling him, “I can’t see you.” It might as well be the thesis for this film, which is all about seeing and not seeing. We see Frankie always. Harris Dickinson, an English actor, plays him to brooding perfection. It is a role that could be all surfaces. The glares. The surly moods. The furrowed brows. But there is pain beneath it and Dickinson is great at distilling it. But as great as he is, we do not really see Frankie because he is unknowable. He does not want to be seen. And he does not want to see himself. So, what we have is a beautifully opaque film. Frankie is a mere shadow on the beach, as he tries to form connections. He consistently jokes that his band of colleagues are not his friends, but it’s a joke that comes from truth. They are not, not really. He is alone.

And so, the very last scene of the film watches him traipsing through his Brooklyn projects alone and on the beach. The camera shoots him almost as if he is in the dark, because he is. All alone and all in the dark. It’s a good metaphor for the year, and Hittman does a good job of distilling it. “Beach Rats,” then, offers a great experience in desolation. Rarely fun to watch, but compelling.

Have a comment? Write to Andrew at almasydk@gmail.com