HARARE, (Reuters) – Zimbabwe President Emmerson Mnangagwa appointed senior military officials to top posts in his first cabinet on Friday in what was widely seen as a reward for the army’s role in the removal of his predecessor, Robert Mugabe.

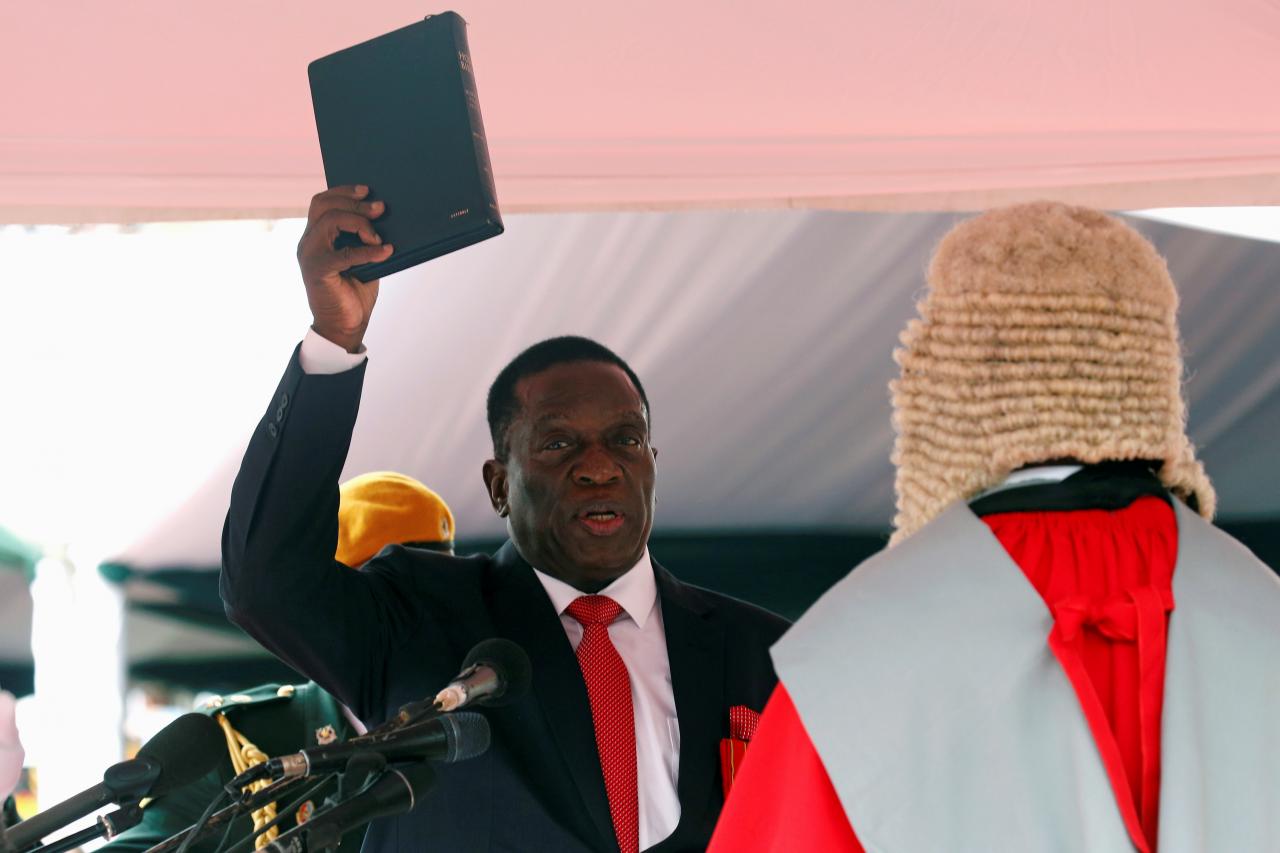

Mnangagwa was sworn in as president a week ago after 93-year-old Mugabe quit in the wake of a de facto military coup.

Mnangagwa, a former state security chief known as ‘The Crocodile’, made Major-General Sibusiso Moyo foreign minister and gave Air Marshal Perrance Shiri the land portfolio.

He brought back Patrick Chinamasa as finance minister once more despite his chequered record in that post previously.

Most Zimbabweans remember Moyo as the khaki-clad general who went on state television in the early hours of Nov. 15 to announce the military takeover that ended Mugabe’s 37-year rule.

Shiri is feared – and loathed – by many Zimbabweans as the former commander of the North Korean-trained ‘5 Brigade’ that played a central role in the so-called Gukurahundi massacres in Matabeleland in 1983 in which an estimated 20,000 people were killed.

“For most observers, this looks like a reward for the military – or more specifically like the military asserting its authority,” London-based political analyst Alex Magaisa wrote on Twitter.

Mnangagwa dropped allies of Mugabe’s wife, Grace, but brought back many Mugabe loyalists from the ruling ZANU-PF party, disappointing those who had been expecting a break with the past.

“Zimbabweans were expecting a sea change from the Mugabe era. After all, had there not been a revolution, or so they thought?” Magaisa said.

New information minister Chris Mutsvangwa, leader of the powerful liberation war veterans, was not immediately available for comment.

Mnangagwa’s opponents from Grace Mugabe’s ousted G40 faction derided the line-up as old wine in a khaki bottle.

“Even #Nigeria didn’t have so many commanders in Cabinet in its coup days!” former information minister and G40 leader Jonathan Moyo, who remains in hiding, said on Twitter.

Chinamasa, a lawyer by training, had been finance minister since 2013 until he was shifted to the new ministry of cyber security in a reshuffle this year.

During his time in charge, though, the economy stagnated, with a lack of exports causing acute dollars shortages that crippled the financial system and led to long queues outside banks.

The issuance of billions of dollars of domestic debt to pay for a bloated civil service – a key component of the ZANU-PF patronage machine under Mugabe – also triggered a collapse in the value of Zimbabwe’s de facto currency and ignited inflation.

“I had expected a more broad-based cabinet,” said economist Anthony Hawkins, adding that Mnangagwa’s faith in Chinamasa suggested loyalty trumped ability. “Chinamasa’s appointment was to be expected, notwithstanding his appalling record.”

With elections due next year, Mnangagwa needs to deliver a quick economic bounce and has made clear he wants to curb wasteful expenditure, pointing out that his cabinet has 22 ministers compared to Mugabe’s 33.

One of his most pressing tasks will be to patch up relations with donors and the outside world and work out a deal to clear Zimbabwe’s $1.8 billion of arrears to the World Bank and African Development Bank.

Without that, the new administration will be unable to unlock any new external financing.

British Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson told Reuters this week London was thinking about extending a bridging loan to Harare to allow this to happen, although said it depended on “how the democratic process unfolds”.