One must have to be a dolt to believe that the treatment at present being meted out to the sugar workers is because the country cannot afford to keep them at work. One only needs to ask oneself if these workers would have been treated in this manner had the PPP/C been in government, to which the answer would be a resounding no. What we have here is not the absence of funds as much as it is the redirection of priorities. Simply put, equal citizens they may well formally be, but on the government’s agenda the sugar workers do not have the requisite level of priority to be kept in employ: end of story!

Similarly, one would also be extremely foolhardy to believe that now or in the near future, ordinary citizens are likely to witness any appreciable improvement in their standard of living as a result of the present brutalization of the sugar workers. It may be possible to deploy the subsidies going to the sugar industry more profitably, but speaking in a faraway land to an audience ignorant of the behaviour of his government towards a hefty proportion of the working class, it was no less a person than our president who called upon his audience to view development as a dialectical relationship between profits and human livelihood with a focus on the latter. At least since the 1970’s the signs were there that the sugar industry could not perennially depend upon protected markets and to survive it needed to be fundamentally reformed. It is not the fault of the workers that the political leaderships – both PNC and PPP – did not begin the reform process in a timely fashion, so why are their heads being so crudely placed on the block?

Similarly, one would also be extremely foolhardy to believe that now or in the near future, ordinary citizens are likely to witness any appreciable improvement in their standard of living as a result of the present brutalization of the sugar workers. It may be possible to deploy the subsidies going to the sugar industry more profitably, but speaking in a faraway land to an audience ignorant of the behaviour of his government towards a hefty proportion of the working class, it was no less a person than our president who called upon his audience to view development as a dialectical relationship between profits and human livelihood with a focus on the latter. At least since the 1970’s the signs were there that the sugar industry could not perennially depend upon protected markets and to survive it needed to be fundamentally reformed. It is not the fault of the workers that the political leaderships – both PNC and PPP – did not begin the reform process in a timely fashion, so why are their heads being so crudely placed on the block?

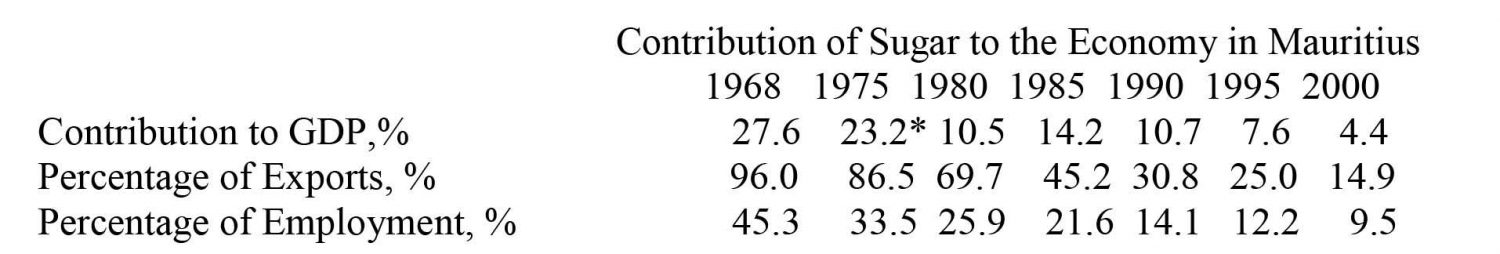

Humane reform of a situation as entrenched as ours must be gradual and cannot be completed in one term of government as the present regime appears intent upon doing. Take the case of Mauritius, which, like Guyana, is a small country that since colonial times has had an economy heavily dependent on sugar. The numbers below show that in 1968, nearly 100% of export earnings came from the sugar industry in which nearly one half of its workforce was employed. Ethnic political conflict was so rife that the common perception of such countries was in 1961 expressed by James Meade, winner of the 1977 economics Nobel Prize. ‘Heavy population pressure,’ he assessed, ‘must inevitably reduce real income per head below what it might otherwise be. That surely is bad enough in a community that is full of political conflict. But if in addition, in the absence of other remedies, it must lead either to unemployment (exacerbating the scramble for jobs between Indians and Creoles) or to even greater inequalities (stocking up still more envy felt by the Indian and Creole underdog for the Franco-Mauritian top dog), the outlook for peaceful development is poor.’ But with dedicated persistence and many political and economic ups and downs, Mauritius has become something of a ‘wunderkind’ in terms of sugar reform and economic development on the African continent.

In passing, in a highly ahistorical piece ‘The Guatemalan model is evidence that Guyana’s sugar industry can once again be viable’ (SN: 18/10/2017), Mr. Wesley Kirton set about trying to convince us that immediate privatization in whole or part is the best pathway to a viable sugar industry. I do not have a difficulty with his general position on privatization, but in the context of my discourse I should indicate firstly that the reform process that brought the Guatemalan industry to its present state of productivity began in earnest some three decades ago (The Coca-Cola Company Review on Child and Forced Labor and Land Rights in Guatemala’s Sugar Industry, March 2015). And, secondly, I am not at all certain that the progressive and congenial picture he sought to paint is not substantially a false one. Apart from the Coca-Cola analysis which made similar points, only months ago, in July 2017, a ‘Rapid appraisal research … in the Guatemalan sugar industry found evidence of a range of indicators of human trafficking for labor exploitation and labor rights violations, including deceptive recruitment, underpayment of wages, forced overtime, child labor, inadequate food and lack of potable water, limits on freedom of movement, and hazardous working conditions’ (https://www.verite.org/report-finds-labor-risks-in-the-guatemalan sugar-sector/)!

In passing, in a highly ahistorical piece ‘The Guatemalan model is evidence that Guyana’s sugar industry can once again be viable’ (SN: 18/10/2017), Mr. Wesley Kirton set about trying to convince us that immediate privatization in whole or part is the best pathway to a viable sugar industry. I do not have a difficulty with his general position on privatization, but in the context of my discourse I should indicate firstly that the reform process that brought the Guatemalan industry to its present state of productivity began in earnest some three decades ago (The Coca-Cola Company Review on Child and Forced Labor and Land Rights in Guatemala’s Sugar Industry, March 2015). And, secondly, I am not at all certain that the progressive and congenial picture he sought to paint is not substantially a false one. Apart from the Coca-Cola analysis which made similar points, only months ago, in July 2017, a ‘Rapid appraisal research … in the Guatemalan sugar industry found evidence of a range of indicators of human trafficking for labor exploitation and labor rights violations, including deceptive recruitment, underpayment of wages, forced overtime, child labor, inadequate food and lack of potable water, limits on freedom of movement, and hazardous working conditions’ (https://www.verite.org/report-finds-labor-risks-in-the-guatemalan sugar-sector/)!

So, over decades the political elite has been wanting in its response to the sugar industry and although I do not believe that we should waste – or steal – the oil bonanza we are about to inherit, I can think of no better project upon which some of those proceeds could be utilized to humanize this mad reform rush which is likely to inflict unnecessary and lasting personal and social injury. That said, I am aware that such pleadings amount to no more than wishful thinking for the logic that underpins the operational framework of the APNU+AFC coalition contains some interrelated inevitabilities that make the government’s present behaviour towards the sugar workers a foregone conclusion.

Firstly, with the best will in the world, standing alone in our social/political context, the APNU+AFC government does not have the political and moral standing to implement the now urgently required reform of the sugar industry in a cooperative and constructive manner. In opposition, it raised our expectations by claiming to understand that only a broad-based government of national unity could have the kind of political reach to perform these types of fundamental changes. However, like so much it has done since, duplicity came to the fore when, having only marginally won at the polls, it claimed to be the national unity government it promised!

Secondly, and very much related to the first, the sugar workers are not adequately prioritised because they do not have any significant political currency with the government. In the latter’s view it matters not if these workers are given equitable attention as they will not vote in politically significant numbers for the coalition anytime soon. I believe this to be true and here very little has changed since the 1950s. Then, the colonial establishment, seeking to win over Indian support, facilitated the rice farmers with tractors but the latter proceeded to vote, en mass, for Cheddi because in their view if it was not for him they would not have got the tractors! It was to mitigate these kinds of negative effects that a national unity government was proffered.

Thirdly, and a conceptual outcome of the previous points, there has long been a belief that the structural nature of labour relationships in the sugar industry, particularly the historical association between the PPP and Guyana Agricultural and General Workers Union, incubate and sustain a bond that contributes significantly to continued Indian support for PPP. In the medium to long term, according to this standpoint, severely weakening this relationship will lead to greater Indian universalism and objectivity in the political process. Of course, a more productive approach would be to accept our people as they are – with all their faults and prejudices – and establish political arrangements that will gradually encourage them to holistically cooperate and construct a more secure and prosperous future. However, with the above operational frame as a backdrop, the present treatment of the sugar workers while extremely sad is not at all surprising.